Sylvia Pankhurst raised phone-tap concerns in 1930s

- Published

Suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst raised concerns about phone-tapping in the 1930s, decades before MI5 revealed it had kept her under surveillance.

At the time, Pankhurst was a prominent human rights campaigner.

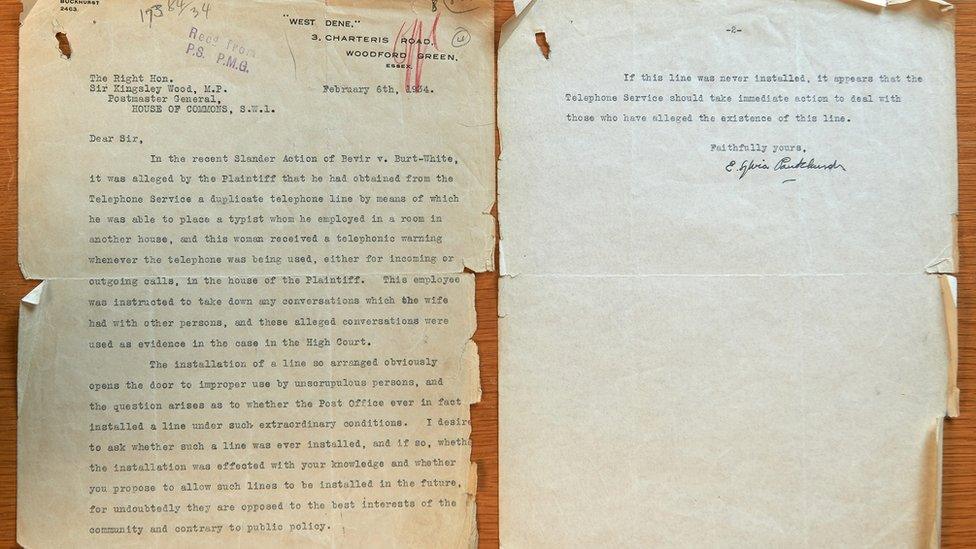

In 1934, she wrote to the postmaster general about the case of a lawyer who had installed a duplicate phone line to eavesdrop on his wife's conversations with a lover.

The letters were discovered in the BT Archives as part of a research project.

Dr Sarah Jackson, an associate professor at Nottingham Trent University, was sifting through a file of old press cuttings about wire tapping as part of her research for a book about literature and the telephone when she found them.

"I was astonished to find letters from Sylvia Pankhurst to the postmaster general revealing her concerns about surveillance," said Ms Jackson.

The letters show that Pankhurst's concerns were triggered by a newspaper report about a gynaecologist who was struck off following an affair with a patient.

Their relationship was discovered by the woman's husband, a solicitor, who had arranged for the Post Office, which then ran the phone service, to install a duplicate line to intercept calls.

Pankhurst's first letter, dated 6 February 1934, refers to the husband arranging for a typist to listen to the wife's calls.

"This employee was instructed to take down any conversations which the wife had... and these alleged conversations were used as evidence...

"The installation of a line so arranged obviously opens the door to improper use by unscrupulous persons," Pankhurst writes.

She argues that such lines "are opposed to the best interests of the community and contrary to public policy".

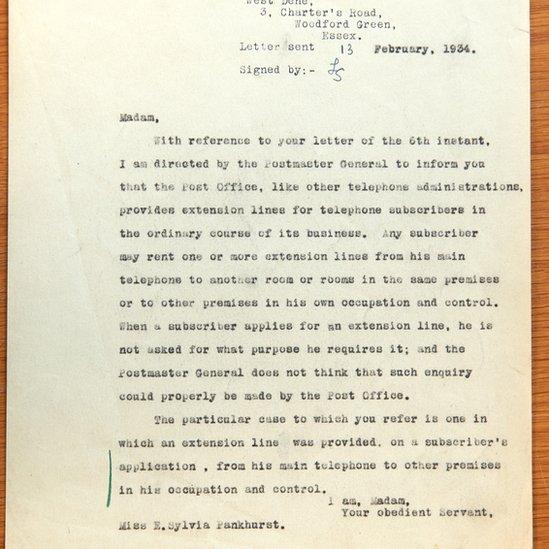

The Post Office response asserts: "The particular case to which you refer is one in which an extension line was provided on a subscriber's application, from his main telephone to other premises in his occupation and control."

However, Pankhurst replies that she herself has an extension in her own house "but I never received notification on my extension when the people in the office were using the telephone for an outgoing call.

"Therefore the telephone line described in the case... must have been something quite special."

She never received a reply to her second letter and handwritten notes between Post Office employees explain that the official response was to "stonewall" her.

In 2004, it emerged that in the 1930s and 40s, MI5 had monitored Pankhurst's movements and phone calls and intercepted her letters.

Dr Jackson, whose research is funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, says it is possible that Pankhurst's concerns about the phone-tapping case were prompted by fears for her own privacy and security.

But she adds that the discovery of the letters is a reminder of the range of Pankhurst's campaigning - from setting up cost-price restaurants to feed the hungry in the poorest parts of London, to supporting the emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia against Italian invasion and colonialism in the mid-1930s.

"In the year that we celebrate the centenary of women's suffrage, the discovery brings home once again the efforts and achievements of this remarkable woman," says Ms Jackson.