Parental conflict: 'It was like a war situation'

- Published

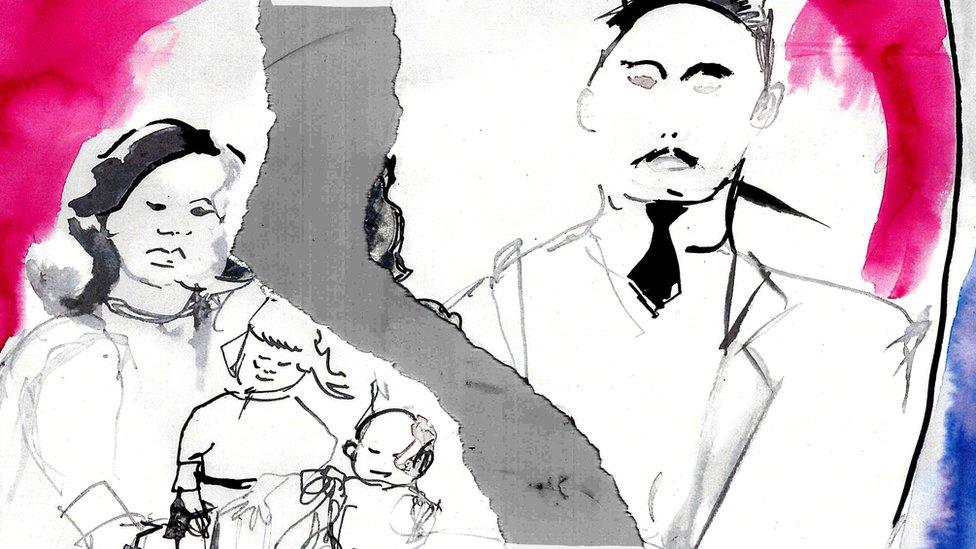

What happens to children when families are torn apart

When parents separate, access to children can be one of the hardest issues to agree.

Sometimes a child will refuse to see one parent - and social workers have to work out what is happening.

The BBC reported on new guidelines in England, which include - for the first time - the possibility of a pattern of behaviour called "parental alienation".

It involves one parent deliberately turning a child against the other.

Our report stirred up memories for some adults of being caught up in high-conflict separations, who wanted to tell us their story anonymously.

Mary's story

Children can feel caught in the middle

"It's a way for the parent to take control of the children - that's how it was for my mum."

Mary was a teenager when her parents separated after a few stormy years in their relationship.

Looking back, she thinks her mother tried to bind her children to her emotionally, partly as a way of feeling secure.

"My mum told us that he'd cheated on her and that he'd left us and didn't love us."

While Mary wasn't told she couldn't stay with her dad, she was encouraged to sabotage her time with him.

After a few years, Mary stopped talking to him and dropped out of contact for a year.

"I thought he was the enemy. I felt it was like a war situation. We were on one side and he was on the other side."

Later Mary got back in touch with her father.

But if she told her Mum she had had a good time visiting him, the atmosphere at home would change.

Either Mary's mother would stop talking to her, or completely withhold affection and lock herself away.

"I had fun with my dad - eventually I came to the conclusion if I didn't have fun with my dad, I wouldn't be punished."

There were other complications. Mary's mother drank too much and sometimes neglected her children.

Looking back as an adult, Mary says she is still dealing with the emotional damage. Damage that has left her with a difficulty trusting others in close relationships.

Mary is in contact with her father now but barely speaks to her mother.

She is trying to work through the impact of these years, in therapy.

"I still have nightmares about that time, less frequent now, but I have them - occasionally. I've accepted they'll always be with me."

Louisa's story

Louise called her dad from a phone box

Louisa was seven years old when her parents broke up and she left to live with her mother.

"I always remember feeling guilty when we drove away from the house, leaving him on his own."

Louisa had a good relationship with her father, whom she "loved to bits".

Her mother's anger scared her. She remembers looking for the number for Childline but being too frightened to ring.

Louisa's mother would tell her and the other children the reason they didn't have certain things was because her dad was withholding money.

It was only later that she found out this wasn't true.

He was always used as a negative, telling Louisa: "You're just like him."

There was a lot of emotional blackmail in her upbringing.

"Don't you know what I've done for you, what he's done to me?" her mother would scream.

Louisa's mother then had a relationship with a man who was violent and who physically threatened her.

"I wasn't allowed to talk to my dad on my own. I'd have to make excuses to walk the dog, so I could get to a phone box to talk to him.

"I was terrified of the repercussions. She would go to work and bar the phone and check if he'd called."

Her mother moved them so far away that it became even harder to see her dad.

Usually, her father passed on birthday cards from her grandmother but one year one was sent to their home direct.

"Because I got a card, she didn't speak to me on my birthday."

In her later teenage years, Louisa left to live with her father.

It wasn't easy at first to rebuild their relationship, as contact had been intermittent.

Louisa says she now struggles to have any feelings for her mother. "It's a blank."

Her greatest sadness is her younger siblings, who were too little when her parents split to have a clear, untarnished, memory of their father.

Moving on

Dr Andrew Reeves, chair of the British Association of Counselling and Psychotherapy, says people who have been through these experiences can be left with unresolved anger, and difficulties with trust within their own adult relationships.

"There's no template for a solution. It's important to be able to make sense of it as an adult, and get support in making decisions that are best for you."

He suggests that trying to bring an adult perspective can help progress towards a position of neutrality, when thinking about what has happened.

Some people seek counselling, others work through issues in their close relationships.

Either way he says a decision about whether to get back in contact with a parent is highly personal.

Dr Reeves said it needs to be approached with realistic expectations of what might come out of it.

Childline is open 24 hours a day, 365 days a year on 0800 1111.