'You can fly planes': The students who are inspiring younger siblings

- Published

"Why do you want to be an apprentice and be a car technician, when you can go to university and do motor-sport engineering?" asks Alison.

"Why fix cars when you can make cars?"

The first in her family to go to university, Alison is now trying to inspire her three younger brothers, aged 16, 15 and seven, to follow in her footsteps.

According to researchers from Brunel University London, first-generation students such as Alison can be pivotal when it comes to persuading under-represented groups to consider studying for a degree.

'Fly planes'

Their research, external says these students have a social-mobility "slipstream effect" on those close to them, which can help to widen access to university education.

Alison told the researchers how her move to university had started to change her eldest brother's vision for his future and made him challenge his school's suggestion that he completed an apprenticeship and became a car technician.

"I said to him, 'You can do aviation and pilot training and fly planes,'" she told the researchers.

"At school you don't hear about the things you can go on and do."

'Cultural capital'

The Brunel research says: "Alison has become an educational role model to her siblings as she has superseded her mother's educational achievement and knowledge.

"This has given her both the cultural capital and personal ability to directly challenge her brother's perceptions and his school's trajectory for him."

Another first-generation university student, John, whose mother is a single parent and lives above a shop on a council estate, told the researchers: "I suppose my brother will now have to do a degree as well. He's much cleverer than I am.

"I'll probably give him a lot of help because it's now part of my experience. It will make it a hell of a lot easier for him than it was for me when I came."

Paula, also the first in her family to attend university, told the researchers her younger brother had been thinking about joining the Army but her university stories were making him reconsider.

"He is interested in my experiences, in what I'm doing," she said.

"I tell him about the lab sessions we have, then he gets really excited because, obviously, it's in a lab and it's like sciencey stuff.

"He does listen a lot, for sure, he does ask a lot of questions, so I reckon he's thinking about it [university]."

And the effect is not just on younger siblings - the study found parents too were influenced by a young person's move into higher education.

Paula told the researchers: "My mother is going - [she] is retaking one of her GCSEs so she can do her A-levels and go to uni. She is trying to do occupational therapy or be a physio.

"I said, 'Well, yeah, you can do that. You can always go back to college and get A-levels.'"

'Untapped potential'

The research paper is based on a year-long project at a London-based campus university where researchers conducted in-depth interviews with eight first-generation students.

And it concludes that these students have "relatively untapped potential" to become role models.

"While the entrenched discourse about first-generation students may construct them as 'at risk' of attrition and therefore as 'risky' students, the narratives presented here provide a counter to this, acknowledging the potential they can offer in terms of widening participation and support among under-represented groups," it says.

"How we conceptualise these students needs to change, with them and their families reimagined as a key resource for family learning, social mobility and university practice."

'Role modelling'

Report author Dr Emma Wainwright said: "Universities need to engage more thoroughly with the families - parents and siblings - of their students.

"These institutions should become sites for learning interaction, experience and role modelling based on the family unit, however it is configured."

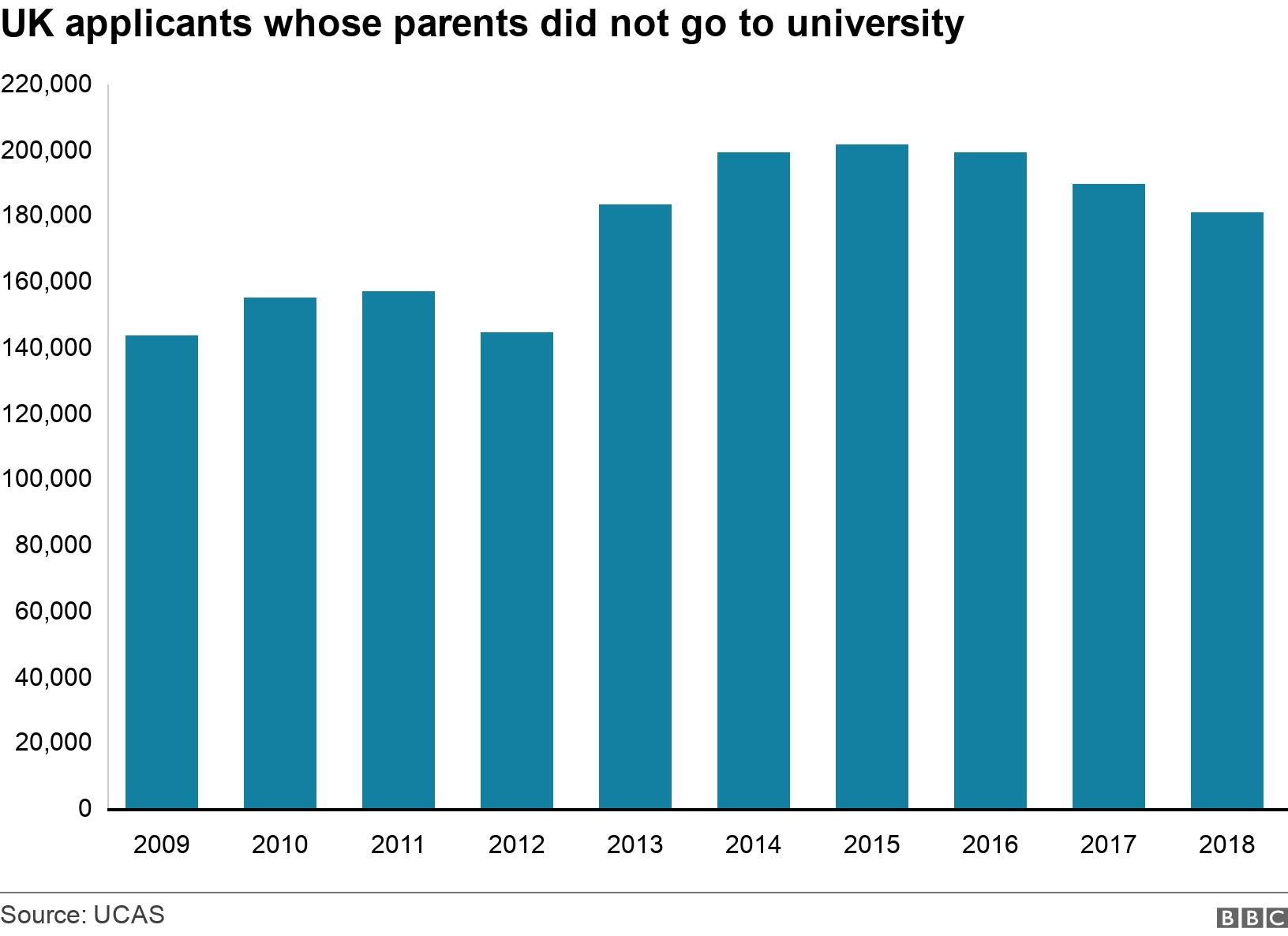

Figures from the university admissions service, Ucas, show the numbers of UK applicants whose parents did not go to university has gradually risen since it started collecting this data.

In 2009, 143,585 applicants were not from graduate homes. This compares with 181,300 in 2018, with a peak of 201,625 in 2015.

Universities UK said it was committed to widening access and ensuring "the success of all their students, regardless of their backgrounds", pointing to the success of schemes such as Durham University's first generation scholars network, external and the University of Sussex's first-generation scholars scheme, external.

A UUK spokeswoman said: "Eighteen-year-olds from the most disadvantaged areas in England are more likely to go to university than ever before and this can help inspire younger siblings or peers to do the same but we know that a number of challenges remain.

"To further improve access to university for first-generation university students, the post-18 education review [which is due to report back to the government in the coming weeks] should make recommendations that support access to higher education for anyone with the potential to benefit from a university education.

"This should include better support for part-time learning and targeted maintenance grants for those most in need."

The Brunel research did not publish participants' real names.

Illustrations for this article created by Emma Russell.

Are you a university student who has encouraged younger siblings to aim for higher education? Email haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also contact us in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7555 173285

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Text an SMS or MMS to 61124 or +44 7624 800 100

Please read our terms of use and privacy policy