Cambridge investigates its slavery links

- Published

The University of Cambridge is to investigate its own historical links with slavery and will examine how it might have gained financially.

It has launched a two-year study that will examine its archives to see whether it gained from the slave trade.

Universities have faced questions about the legacy of links to slavery.

"It is only right that Cambridge should look into its own exposure to the profits of coerced labour," said vice-chancellor Stephen Toope.

Cambridge is to hold a two-year investigation into its links to slavery

"We cannot change the past, but nor should we seek to hide from it," said Prof Toope, who wants the process to help the university "acknowledge its role during that dark phase of human history".

An advisory group has been appointed, chaired by Prof Martin Millett and based in the Centre of African Studies, which will examine the university's archives, libraries and museums to find connections with slavery.

"We cannot know at this stage what exactly it will find but it is reasonable to assume that, like many large British institutions during the colonial era, the university will have benefited directly or indirectly," said Prof Millett.

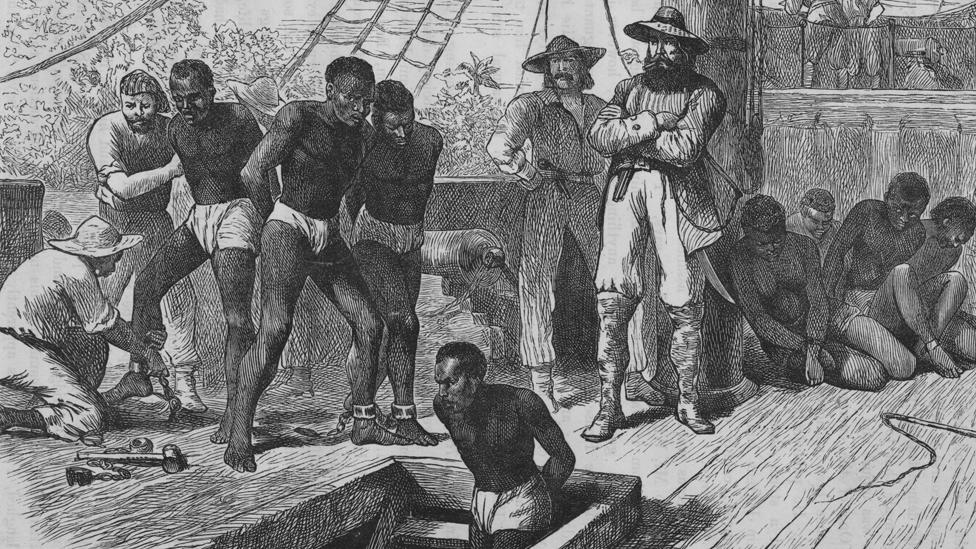

Oxford University faced a dispute over its statue of Cecil Rhodes

"The benefits may have been financial or through other gifts.

"But the panel is just as interested in the way scholars at the university helped shape public and political opinion, supporting, reinforcing and sometimes contesting racial attitudes which are repugnant in the 21st Century."

It will also consider how the university might make reparation for any links to the legacy of the slave trade - whether in symbolic terms, such as monuments or re-naming buildings, or in funding bursaries or foundations.

Prof Millett highlighted that the University of Glasgow is setting up a centre for the study of slavery, after it found that it had received donations in the 18th and 19th Century, derived from slave trade profits, which could be worth up to £198m in present day value.

Universities in the UK and the United States have faced scrutiny about whether they had benefited from slavery and coerced labour, particularly during the 18th and 19th Century.

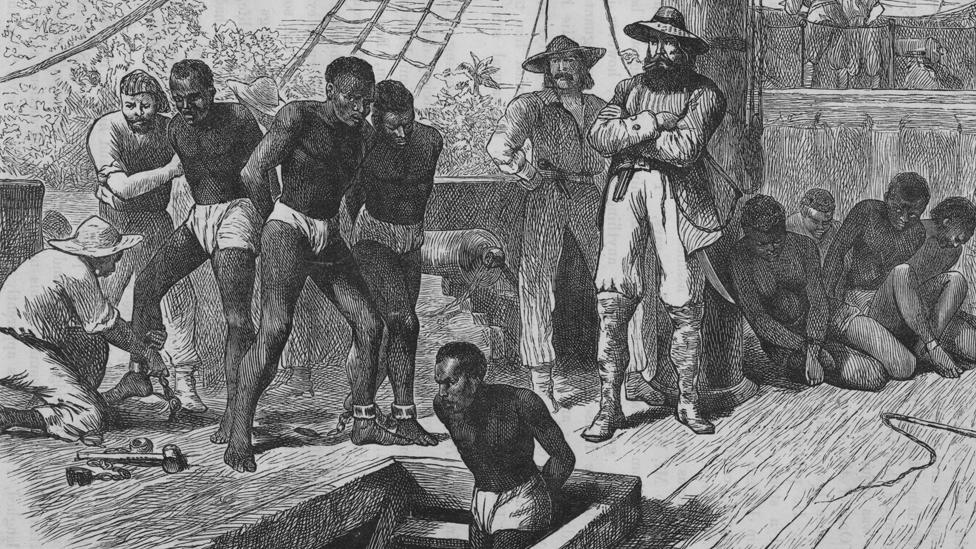

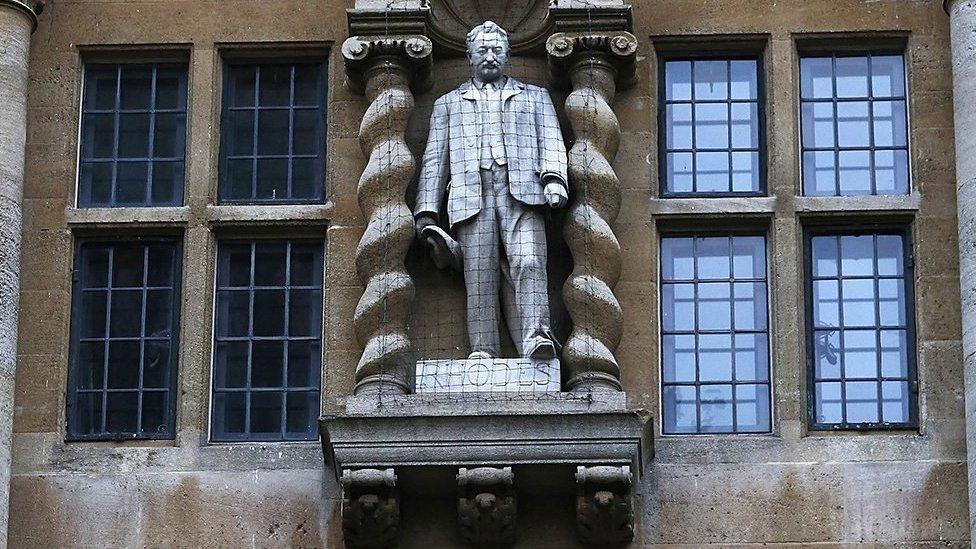

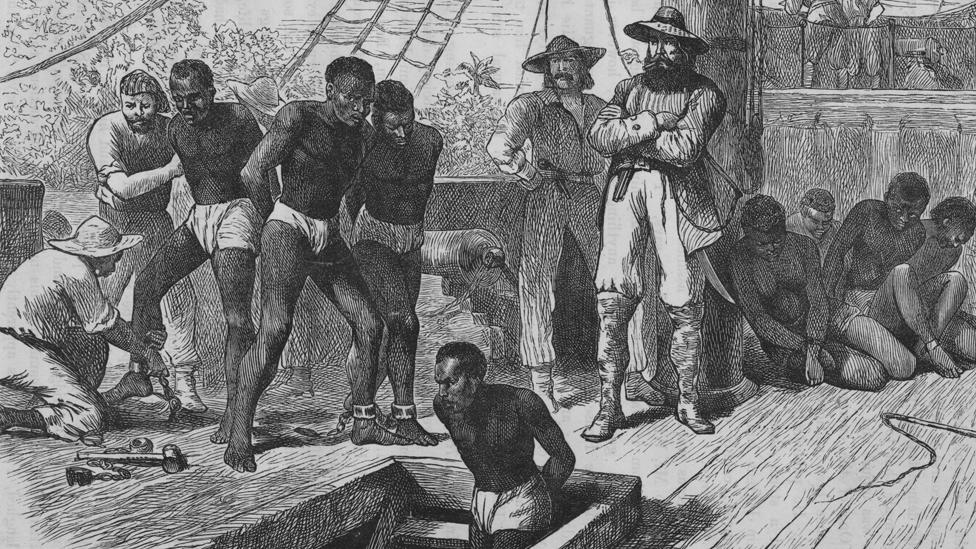

Britain's involvement in the slave trade

British merchants were among the main participants in the Atlantic slave trade, transporting about 3.1 million Africans (of whom 2.7 million survived the journey) to the colonies in the Caribbean, North and South America and to other countries.

The three most important ports for British slave traders were London, Bristol and Liverpool.

Their ships sailed to the west coast of Africa, where they traded manufactured goods for captured African people.

In 1807, the British government passed an act of Parliament abolishing the slave trade throughout the British Empire - but slavery itself would persist in the British colonies until its final abolition, in 1838.

Reflecting the past

There have been questions about whether such connections are still visible, such as in statues and the names of buildings, and how such legacies should be acknowledged.

Georgetown University has sought to help individual descendants of its former slaves

At the University of Oxford, there was a long-running dispute over a statue to Cecil Rhodes, a controversial 19th Century colonial politician.

At Harvard University, in the US, the word "master" was removed from academic titles because of concerns that it had echoes of slavery.

Harvard's law school also changed its official seal because it included the crest of a brutal 18th Century slave trader.

Georgetown University, also in the US, agreed to offer support to the descendants of more than 200 slaves that the university had sold in the 19th Century.

The chair of governors of the University of East London has called for any universities in the UK that have a link to slavery to contribute to a £100m reparation fund, which would support ethnic minority students.

Another UK university, Newcastle, also recently made a discovery that showed how recent the connections with slavery could be.

Researcher Hannah Durkin found the identity of the last known survivor of the transatlantic slave ships.

The former slave, Sally Smith, had been brought from West Africa to the US in 1860, and lived until 1937 in Alabama, staying for more than 70 years on the plantation where she had been enslaved.

- Published17 December 2015

- Published25 February 2016

- Published3 April 2019

- Published25 October 2018