Students want parents to be told in mental health crisis

- Published

- comments

Two-thirds of students support universities being able to warn parents if students have a mental health crisis, an annual survey suggests.

There have been concerns about student suicides and the survey indicated worsening levels of anxiety on campus.

Only 14% reported "life satisfaction", in this study of 14,000 UK students.

And most thought even though students were independent adults, universities should in an emergency be allowed to disclose information to parents.

Published by the Higher Education Policy Institute (Hepi) and Advance HE, external, this is one of the biggest annual reports into the views of those currently studying in the UK's universities.

'Under pressure'

The 2019 survey showed continuing concerns about students' well-being - with just 18% saying they were happy, 17% saying their life was "worthwhile" and only 16% having low levels of anxiety, with all these student figures being considerably worse than for the rest of their age group.

It showed 66% supported universities being able to share concerns with parents or a trusted adult if there were "extreme" problems - and a further 15% thought universities should be able to contact parents in "any circumstances" where there were mental health worries.

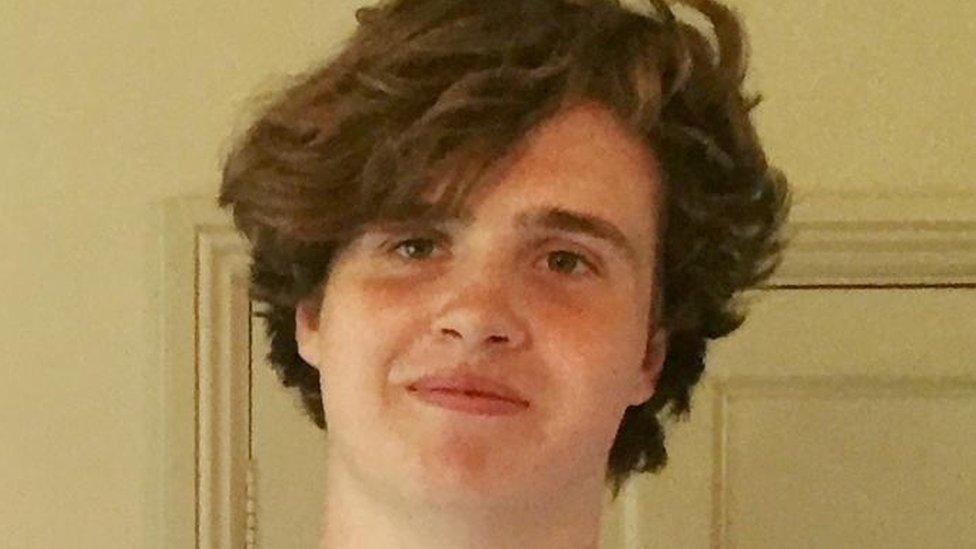

James Murray speaking in 2019 about involving parents when students are in serious need of support

There were 18% who thought universities should never be allowed to get in touch with parents.

The University of Bristol, which has faced a number of student suicides, has a scheme in which students can opt-in to allowing parents or trusted adults to be contacted - with a take-up of 95%.

Ben Murray, after the death of his son James who was a student at Bristol, has worked with the university on improving support.

"Mental health has been ignored for too long and we need to encourage disclosure at exactly the time when young adults need it most - transitioning from school to university," said Mr Murray.

Nick Hillman, director of Hepi, said the survey showed the pressure that some students could feel from being "away from friends and family" and how some struggled with the "big break" from home.

Report author Jonathan Neves said it showed how students felt "under a lot of pressure".

Sir Anthony Seldon, vice-chancellor of the University of Buckingham, said: "The survey dispels the fiction that students don't want their parents and guardians involved.

"It's incredibly difficult for many students to transition to university. And having parents and guardians more involved when appropriate is good sense, and can only help, including helping save lives," said Sir Anthony.

Value for money

Last month, Prime Minister Theresa May welcomed a report from Philip Augar calling for a cut in tuition fees in England - saying the maximum should be reduced from £9,250 to £7,500 per year.

The survey showed that for the 29% of students who thought they were getting "poor" or "very poor" value for money, the biggest factor was the level of fees.

The proportion saying they were getting "good" or "very good" value had risen - but only to 41%.

Chris Skidmore, the universities minister, said that if fees were reduced as the Augar review recommended, then there would need to be "top-up" funding for universities to replace the lost income.

Speaking at the Hepi conference, he said that improving funding for further education should not be at the expense of higher education, saying "you can't rob Peter to pay Paul".

He argued that there should be more students going to university rather than less - and he reiterated his opposition to setting a minimum grade threshold, such as requiring students to get a least three D grades at A-level.

Mr Skidmore said this would be an unfair block on those who did not have the opportunity to get good A-levels at school, but who "flourished later on in life".

Better teaching

The student satisfaction survey showed that within the UK, students in Scotland, where there are no fees for Scottish students, were much more likely to think they had good value, compared with those in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The most common driving factor for those with positive views was the quality of teaching - and the report suggested improving teaching was the way to increase perceptions of good value.

But the survey showed the average number of "contact hours", where students are directly taught in class, had not increased significantly - from 13.4 hours per week in 2015 to 13.9 hours this year.

Mr Hillman said the survey showed "students want to be stretched, they want clearer feedback and they want more support for mental health challenges".

- Published2 May 2019

- Published29 October 2018

- Published30 September 2015