Global literacy targets already off track - Unesco

- Published

Writing on the school wall in Senegal: Progress to widening access to education has stalled, says UN report

Promises by world leaders to raise global education standards by 2030 are unlikely to be kept, warns the United Nations' education agency.

Unesco says on current trends, 30% of adults and 20% of young people will still be illiterate in poor countries.

There are 262 million young people without access to school, with the worst problems in sub-Saharan Africa.

The UN agency warns that the numbers missing out on education are unlikely to fall much in the next decade.

The report examines progress towards global targets, the "sustainable development goals", which in 2015 the international community committed to achieve by 2030.

Progress stalled

These included promises on education - but after four years, the projections from Unesco show, they are already off track and unlikely to be achieved without a significant change of direction.

About 18% of children are without school places - and Unesco's report says on current trends this will have fallen to 14% by the end of the next decade, which will still mean 225 million out of school.

There had been more progress in the early years of the century, particularly in reducing the number of primary age children who do not even get the first basics of an education.

Refugees in Chad: Conflicts have disrupted the educations of tens of millions

The out-of-school rate for primary years had fallen from 15% to 9% between 2000 and 2008 - but, the report says, progress then seemed to stall.

This has been linked to a reduction in overseas aid in the wake of the financial crash.

But it also reflects the fact there is a hard-to-reach group of children whose chances of going to school have been disrupted by war and violence, being forced to become refugees, corruption and political failure.

Lack of teachers

There are inequalities of access - such as barriers to girls and rural families getting an education.

But the biggest gap is related to poverty - with only 4% of youngsters in low-income families staying on to the end of secondary school.

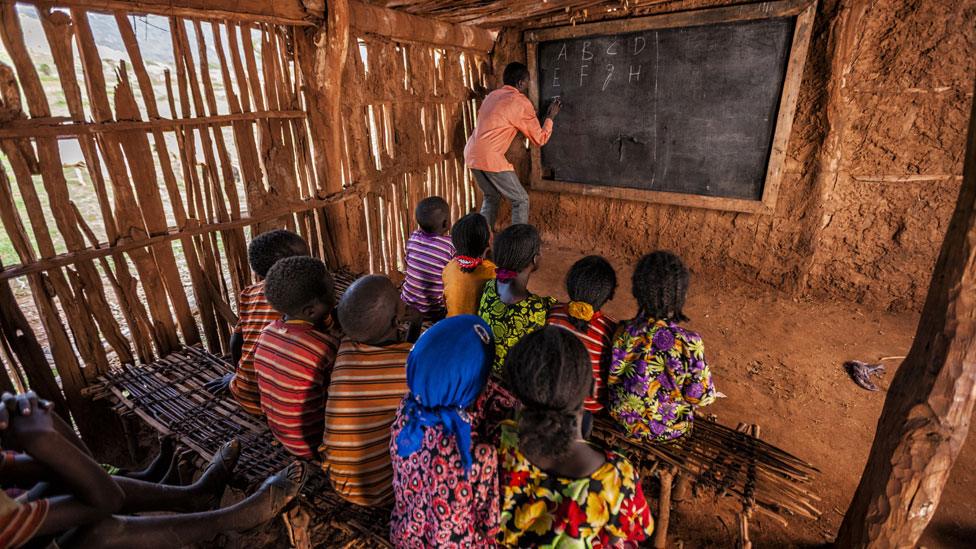

A classroom in Uganda: The biggest challenges to get all children in school are in sub-Saharan Africa

The report also highlights practical problems, such as an acute lack of trained teachers.

The proportion of teachers with at least basic training has fallen in sub-Saharan Africa, so the problem is worse now than at the beginning of the century.

The growing population has also been a challenge in this region - and 54% of all the children without school are now in sub-Saharan Africa, compared with 41% in 2000.

Across the world, the Unesco report says, by 2030 about 90% of adults will be literate. But in low-income countries, there will still be 30% of adults who are illiterate.

Damaged in war

Unesco also highlights the differences in outcomes between developing countries.

Liberia is among the least likely to provide education for all its children, with many school buildings being damaged by conflict and many teachers leaving the country.

Ethiopia has seen an increase in access to schools

But Ethiopia is seen as making much better progress, investing more than a quarter of its budget on education and raising the numbers of girls in school and female teachers.

Nepal and Afghanistan are also seen as making considerable improvements in access to education.

Broken promises

This is the latest in a series of missed education targets after high-profile international pledges - despite education being seen as important for improving health and prosperity in poorer countries and preventing extremism.

Promises made in 1990 to ensure access to primary education were not achieved by the deadline of 2000.

Despite hardships, Afghanistan is commended for widening access to school

These were replaced by millennium goals for improving global education, which were missed by the 2015 deadline.

These were followed by the sustainable development goals set in 2015.

These promised that all children would be able to complete primary and secondary education by 2030.

But, the report from Unesco says, after almost a third of the 15-year target has elapsed, the trends suggest these goals are likely to be missed.

"The world is far off track on achieving international commitments to education," the report says.

"For several years now, no progress has been made on access into primary and secondary education. Only one in two young people complete secondary school."

- Published9 April 2015

- Published11 October 2017

- Published13 September 2017