Is society's 'Man up' message fuelling a suicide crisis among men?

- Published

Happy days - James and his family

Suicide is the biggest killer of men under the age of 50. What is it about being male in the UK that is fuelling this mental health crisis?

After nearly 20 years suffering recurrent bouts of depression - virtually in silence - at the age of 39, James had reached the end

The sporty, laddish, joke-cracking executive had even thought about ways of killing himself.

"The clarity I had thinking about it was completely fogged over by what that would do to the people close to me," he says.

"Did I think they would be better without me? Yes.

"But in the end what stopped me was thinking of my children and my wife, about what it would do to them."

Like so many men, James felt unable to reveal how he was feeling. He kept it hidden under a habitual light-hearted facade and did not even tell his wife.

Then, something small happened at work. Now, he cannot even remember what it was - but because of how he was feeling at the time, it was big enough for him to decide he had to kill himself.

'Laddish bravado'

As he thought over his plan yet again, James shut himself in the work toilet, crying, but something made him call a friend.

He recalls sobbing into the phone for one and half hours, telling his friend, Claire, how he was "not coping well" - massively minimising how he really felt.

And he recalls how she stayed on the phone listening, while he sobbed. He didn't tell her he was planning to take his own life.

"She talked me down, so to speak. That was the initial opening of the dam," he says.

Reaching out like that for the first time saved his life and he was soon admitted to an intensive treatment centre.

Depression had first hit James during his first year at university, at the age of 20, but he had felt unable to let his friends know what he was going through.

A member of the football team and the cricket team, he went out drinking with his teammates and appeared to others to be having the time of his life.

"I felt I had to be part of it, to fit into the team. To be part of that, I had to have that laddish bravado - I think that's why men can struggle so much," James says.

"Then I got caught in this whirlpool of despair - should I be laddish even if I didn't enjoy being laddish?

"I was trying to fit into how society thinks young men should act."

Mo Running events aim to raise awareness of men's mental health issues

When he finally sought help from his GP, he was not offered any counselling, just anti-depressants. Prozac had recently arrived in the UK.

Would some sort of talking therapy, the preferred treatment option today, have helped him?

He is not so sure he would have allowed it to.

"Men don't feel comfortable in a situation where they are made to express their feelings," James says.

"With therapy, it's a case of sit down in a room and there's no escape.

"To be honest, therapy is still a dirty word for most men."

'Get on with it'

And, in a profession vastly dominated by female practitioners, it may be unsurprising that more than two-thirds of people who seek help for a mental-health problem are women.

Mental health champion Lee Cambule recently told a committee of MPs investigating the issue, external: "There's this perception of men that they should 'man up' and 'just get on with it', that they should be strong in the face of this adversity, and this makes it very difficult for them to then open up and seek help.

"A lot of the things about being a man or boy in this situation makes it very difficult to reach out and get the help that's needed."

Simon Gunning, chief executive of Campaign Against Living Miserably (Calm), told MPs masculinity was often equated with having what it took to put food on the table.

"It has been defined as this strange conflation of stoicism and strength, meaning the strong silent type," he said.

But, for many men, it was actually harder to communicate than to stay silent.

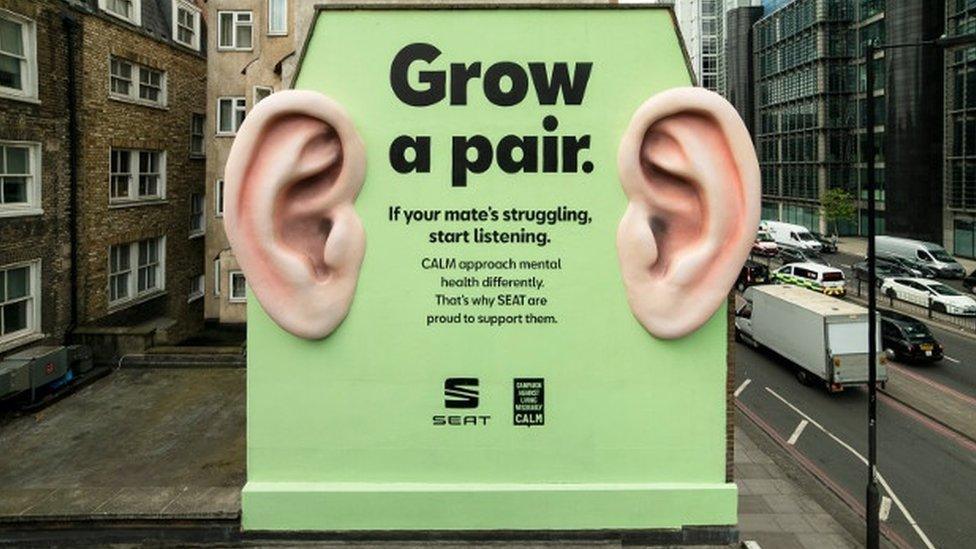

Calm has sought to bust these stereotypical messages, with clever campaigning that flips them on their head.

Martin Robinson, who edits the Book of Man website, says men can end up going to deeper depths of despair than women before asking for help.

This is all about the message society gives boys and men about staying tough, he says.

"I do think it's because they've been informed throughout their lives that they are not supposed to have these problems, so many people keep it hidden away until they are at the point of deep distress," he says.

'Face the pain'

Adam Afghan, who was deeply troubled with obsessive suicidal thoughts several years ago, says: "I kept pushing them to the back of my mind, over and over again.

"And these thoughts gradually got worse and worse to the point that the only way I could think of getting these thoughts away from me was to commit suicide."

Fortunately, he found the courage to break cover and seek help from his mother, who found him a therapist.

Some campaigners feel a different approach is needed - that enables men to open up and talk without their mental health issues being the explicit focus.

Men's health charity Movember, external organises themed Mo Running events that bring men together to run but allow them to chat over mental health issues, external while they do so.

James, who as a community champion shares his story during such events, found that running shoulder to shoulder with others made it easier for his fellow runners to open up about their experiences and feelings.

'True courage'

But Adam says it's time for men to stop keeping things bottled up and denying their feelings.

"I feel that manning up is what men do," he says, "we think we should just take it on the chin.

"But it's actually the opposite - that's not a brave thing, to suffer in silence.

"The really courageous thing to do is to face your problems, face the pain that you're suffering.

"Trying to fix it, that's what's really courageous."

If you are depressed and need to ask for help, there's advice on who to contact at BBC Advice.

Alternatively, call Samaritans on 116123 or Childline on 0800 1111.

- Published5 December 2018

- Published4 September 2018