Make failing to report child abuse illegal, say victims

- Published

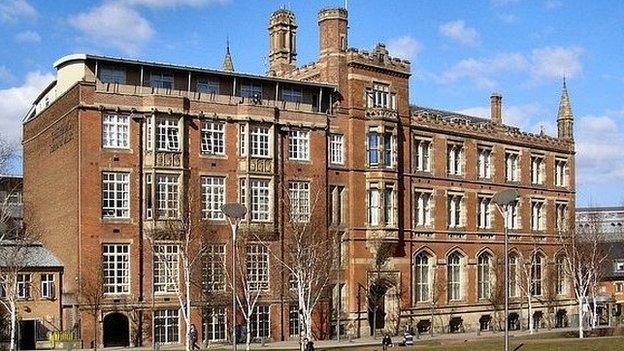

The schools named include Chetham's in Manchester, one of the UK's best-known music schools

It should be illegal not to report child abuse, victims have told the child abuse inquiry at the start of its investigation into boarding schools.

The Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse heard of an "overwhelming body of evidence" to support the introduction of "mandatory reporting".

The inquiry was given a summary of past emotional, physical and sexual abuse at private residential schools.

A senior IICSA lawyer warned that such abuse could happen again.

The residential schools phase is one of 14 separate investigations, external by the inquiry.

In 2016, the government in England carried out a consultation which examined the case for mandatory reporting - and this is a field where the inquiry is likely to make key recommendations.

If a law were introduced, it would be illegal for professionals working with children not to pass on reports of abuse.

In 2014, Wales introduced a duty to inform authorities of suspicions.

The inquiry is beginning two weeks of hearings looking at how to prevent abuse happening again, with a focus on residential private boarding schools, along with special schools for music and for children with special needs.

A 'rotten' institution

The inquiry's lead counsel read a summary of harrowing evidence of past abuse at seven private boarding schools, all of which have been closed or taken over by other bodies.

Fiona Scolding QC described the abuse at St William's in Yorkshire, run by the De La Salle Brothers, a Roman Catholic order until 1992.

She said boys were raped and sexually assaulted by the head teacher, Brother James Carragher, and other teachers.

"This institution," she said, "seems to be rotten to its very core".

The inquiry also heard that at Sherborne Prep school the head teacher, Robin Lindsay, would walk around in his pyjamas, "exposing himself, stinking of alcohol and tobacco," she said.

But his behaviour continued "unimpeded" for 24 years. He was regarded as eccentric, despite being a "fixated paedophile" who posed a risk to children.

He died in 2016.

Boris Johnson was a pupil at Ashdown House

The inquiry has examined past abuse at Ashdown House, in East Sussex, once attended by Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

Evidence against one teacher, Martin Haigh, between 1973 and 1975, was set out in detail to the inquiry.

He would make boys masturbate, while standing in a circle, telling them it was a "scientific exercise".

The headmaster of two schools, St George's and Dalesdown, Derek Slade, committed "calculated, and deliberate brutality".

"Every student was scared witless of him," Ms Scolding told the inquiry.

After fleeing abroad, having used the identity of a dead child, Slade was convicted of serious child abuse in 2010 and jailed for 21 years. He died behind bars.

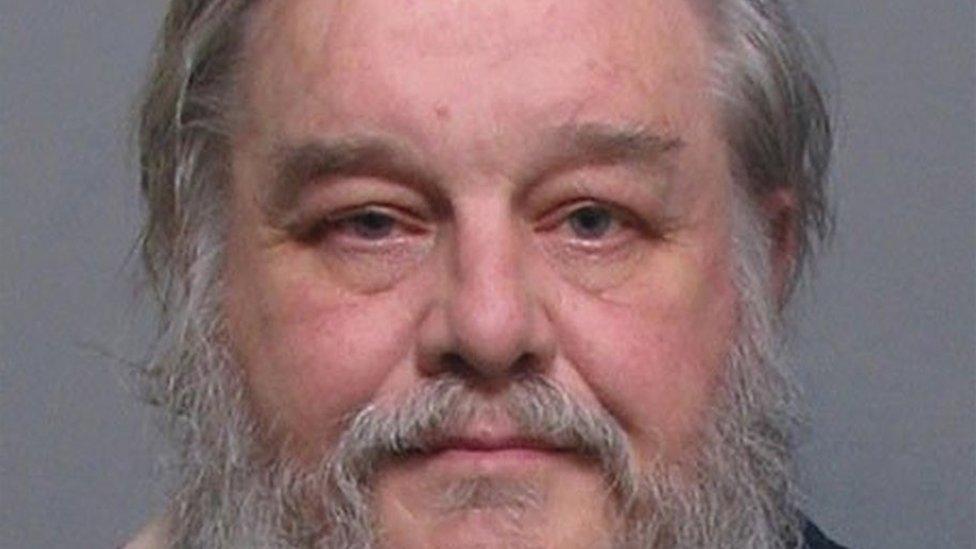

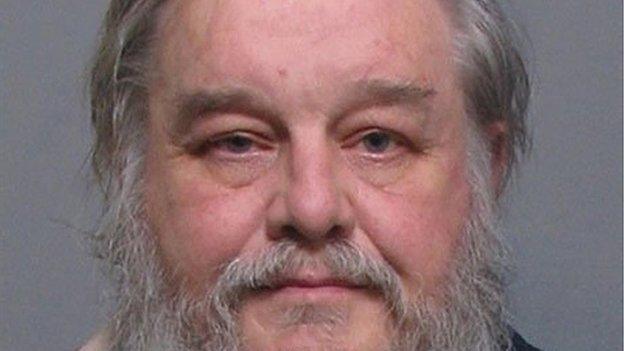

Derek Slade abused boys between 1978 and 1983 at schools in Norfolk and Suffolk

Ms Scolding said there were few procedures for safeguarding, whistleblowing or staff training in those days.

"Before individuals start decrying red tape and bureaucracy, they may wish to reflect that in an era of almost total self-regulation, these kinds of behaviours went unchecked and undiscovered."

She said the current system may have improved, but she said there were still many cases where abuse could happen.

Chetham's School

The inquiry will also look at more concerns about four music schools, in particular, Chetham's in Manchester where Michael Brewer abused one of his students, Frances Andrade, in the 1970s and 1980s.

Ms Andrade took her own life after giving evidence against him in 2013.

Frances Andrade took her own life soon after giving evidence against a former teacher

Another teacher Christopher Ling, who taught strings, acted like a "rather dated lothario", Ms Scolding said.

"He is described as having a leather jacket, unbuttoned shirts and a medallion, crocodile shoes and a sports car," said Ms Scolding.

He moved to the United States in the 1990s and shot himself dead when police came to arrest him at his home for extradition to the UK.

Ms Scolding said in the 1980s and 90s he "operated a system of punishment and reward, lowering the children's self-esteem and confidence and making them entirely in his thrall, then engaging in sexual activity with them".

Lawyer Richard Scorer said Chetham's victims had been let down by their school.

"The support has been non-existent. There has been no attempt to reach out to former pupils."

He also criticised the Crown Prosecution Service for failing to prosecute Ling.

On the eve of the inquiry, a spokesman for Chetham's said: "It is a matter of deep and profound regret to Chetham's that former teachers at our school betrayed and manipulated the trust that had been placed in them in order to harm children for which we are truly sorry."

- Published30 September 2019

- Published23 April 2018

- Published3 March 2016

- Published2 September 2015

- Published26 March 2013