'Take in your grandchildren or you won't see them again'

- Published

Grandparents who take in family members' children want more support

"If you don't take these children, the youngest ones will be adopted and you will never see them again."

"Mary", a 72-year-old now raising her four grandsons, recalls the ultimatum delivered to her and her husband by social services.

"I don't ever regret taking these children on," she says.

"I just regret what it's done to us as a family."

The kinship carer

"Mary", who asked BBC News not to use her real name, is one of a growing number of kinship carers in England - relatives or family friends who raise children when social workers decide their birth parents can no longer look after them.

Some receive money from their local authority - but once a guardianship or special-arrangements order is made, the money is means-tested and, many say, not enough.

At a coffee morning, a group of kinship carers, complain that, compared with foster families, they lack support and protection and they want their rights "levelled up with foster care".

People mention big legal fees after disputes with birth parents over access visits, where foster families would be protected by the local authority.

Many of the children face long waits for mental health services, where foster children are often given priority access.

Also, unlike foster families, many kinship carers don't have access to social-worker-monitored contact centres for meetings between the child and their birth parents.

Instead, they have to use public parks or fast-food chains and supervise the visit themselves, which leaves children and kinship carers vulnerable.

One particularly drastic story involved a child being "kidnapped" by a birth parent at one such meeting.

Based on 2011 census data, the charity Grandparents Plus estimates 200,000 children are in kinship care.

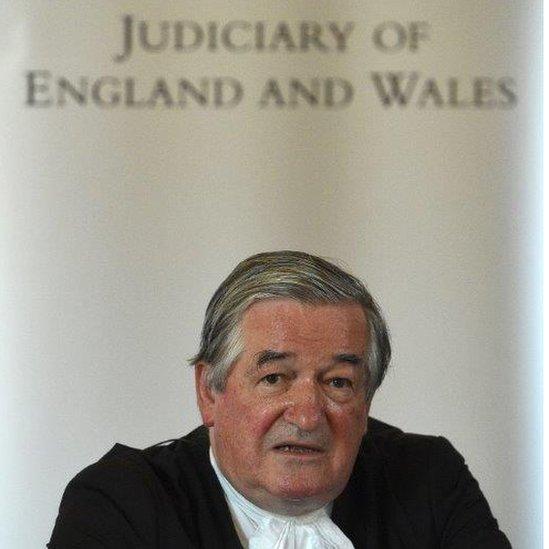

But fewer children have been put forward for adoption since 2013, when a senior judge, Sir James Munby, then president of the Family Division of the courts in England, urged social workers to consider all other options.

"Rightly, this has led to more focus in every case on the feasibility of kinship care and to increasing numbers of kinship care orders," Sir James told BBC Radio 4's The World at One programme.

However, he warned there was now a "serious inadequacy of financial, professional and other support" for kinship carers "in stark comparison to the support available to foster carers and adoptive parents".

He believes kinship carers "could be forgiven for feeling exploited and in a way that can only be detrimental to the welfare of the children they are caring for".

'Drop and run'

"There were six to start with," says Mary.

One of the children is by her side, headphones on, playing a game on his phone.

"The other two were our step-grandchildren," she says.

"One had to go because he had really bad ADHD [attention deficit hyperactivity disorder] and the girl stayed with us for six months but she got herself pregnant, so she left because they asked us to look after the baby as well and we said no.

"I couldn't take on another one. We were all in trauma.

"All social services want to do is get the quickest, cheapest option."

Sir James also raises questions about the assessment of kinship carers and their suitability.

It's not "always as careful and detailed as they should be" and "must be" improved", he says.

Sir James Munby retired in 2018

"Did anyone come to see how these children were?" asks Mary.

"If nanny and granddad are the nice nanny and granddad that they're supposed to be?

"No. Nobody checked up.

"It's drop and run.

"It's a hard slog, because all the children are damaged.

"They were being abused, neglected, mentally abused and physically abused.

"The children weren't clean. They were without food. The mess in the bedroom was as high as the bed.

"The policewoman said she'd never seen anything like it."

'So vulnerable'

Mary says she reported the situation to social services numerous times and the children were finally taken out the home after one of the children was "throttled", leaving a mark noticed by teachers at school.

The grandmother says she'd previously seen burn marks on their arms and red hand-shaped marks on their faces.

"When I look back now, we were so vulnerable. We should have looked into it more," she says.

But, recalling the moment when social services and the police came to their home to persuade them to take the children, she feels she had no other option.

"It's the way they're using words, they're forcing you," she says.

Mary says the financial pressure means they may have to sell their house and downsize.

When the birth mother recently went to court over contact time, she received legal aid - but the grandparents, unlike foster parents, had to cover their own legal fees.

"These parents still have the power to damage their children even though they're not looking after them anymore," Mary says.

As we talk, the grandson at her side throws his arms round her.

"He's a good boy," she says.

"We've given the children better than they had, no doubt, but I thought we'd be able to give them the fun things in life."