Mark Wallinger: The artist who wants to provoke pupils' creativity

- Published

Mark Wallinger said from an early age he had the "stubborn idea" he was going to be an artist

What should school be about? Not "turning out obedient economic units", argues one of the UK's leading artists, Mark Wallinger.

Wallinger, a Turner Prize winner whose work has appeared on the fourth plinth in London's Trafalgar Square, is helping to provoke more creativity and questioning in the classroom.

Leading creative figures are becoming artists-in-residence in schools, sharing their skills in art, music, writing and drama with students, in a scheme backed by the Arts Council and supported by the likes of broadcaster Lord Bragg and historian Sir Simon Schama.

Wallinger is returning the favour for teachers who influenced him when he was at school.

If not quite the hand of fate, the hand of his head teacher in secondary school intervened when he saw the quality of Wallinger's caricatures of teachers - and switched him from technical drawing to art.

In his Essex primary school, he was encouraged by a teacher who was "big on art" - in an era with a more freewheeling approach to learning.

Pallab Sarker says talking to pupils about music is especially useful for young people with stressful lives

The young Wallinger was set up with an easel in the corridor and by an early age he had decided he was going to be an artist.

"It was on a council estate in Hainault, but looking back all the teachers had come to teaching late, in a vocational manner," he says.

Fast forward almost five decades and the 60-year-old artist is sitting in his north London studio.

It's one of those white-walled rooms with works in progress and paint spattered on chairs, as if Jackson Pollock had been practising on the furniture.

Wallinger is now one of the biggest names in international art, but he went for eight years without really selling anything.

He'd left school and had been to art college where his ideas didn't fit in and he ended up working in a bookshop.

"It wasn't straightforward," he says.

The artist has been working with staff and students at Acland Burghley school in north London

Wallinger's reputation began to grow after he studied and then taught art at Goldsmiths, University of London.

But the first time he tried to get a place on the postgraduate course he was turned down and had to reapply the following year.

"You have to be quite bloody-minded," he says, about wanting to be an artist. "It was a stubborn idea."

As a student at Goldsmiths he remembers those who went the extra mile to help.

The Camden sixth-formers are working on producing artwork for a railway footbridge

The artist Bruce McLean was asked to give an evening tutorial in Wallinger's studio. But it didn't have any electricity, so McLean arrived not only carrying ideas, but also a portable generator and lights.

In the artists-in-residence scheme, Wallinger is working at Acland Burghley school in Camden, north London, designing artwork for a railway footbridge.

He wants the young artists to make something that reflects the history and the geography of where they live.

Much of Wallinger's work has been about public places. His images of a labyrinth are on display in every single London Underground station.

Art teacher Andria Zafirakou set up the charity with her prize money from winning the Global Teacher Prize

He wants the next generation of artists to play a bigger role in shaping the public places around them - when so many High Streets are becoming "just bookies and charity shops".

"The idea of civic space is acutely important now - in a sense because it's been privatised or trashed.

"The hearts of a lot of cities have been hollowed out by recessions or the growth of the internet.

"The identities of places are being lost, so people's roots get eroded as well. It's a toxic cycle," he says.

Every tube station has some of Wallinger's work, as part of the Labyrinth project

The schools project, tested in 30 schools in London and set to expand to a further 80 across England, Wales and Scotland, is run by the Artists in Residence charity.

This was set up by London art teacher, Andria Zafirakou , with the $1m (£760,000) prize money she got for winning the 2018 Global Teacher Prize.

As well as giving practical skills and inspiration, the artists show how creativity can be a career.

Ms Zafirakou says teachers have given "fantastic feedback" on tapping into the skills of these visiting artists.

The chairman of Artists in Residence, Pallab Sarker, is also a musician and songwriter who has been visiting Frederick Bremer School in Walthamstow, east London.

He has seen first hand the impact on pupils, in terms of "personal growth and self-understanding" and learning to "think creatively".

An installation by Wallinger at the Tate Gallery in 2007

It can help to build confidence, he says, and be "especially therapeutic for those with difficult and stressful lives".

If any of Wallinger's students are inspired to be artists, how different will it be for their generation?

Becoming an artist is now much more "professionalised" and business-like, he says.

On the upside, there are more galleries and outlets to display work.

But the downside is that the "jargon becomes more and more arcane and impenetrable - and there to shut people out".

Art is also about brands, with the era of the artist as showman and performer.

Wallinger seems more reticent.

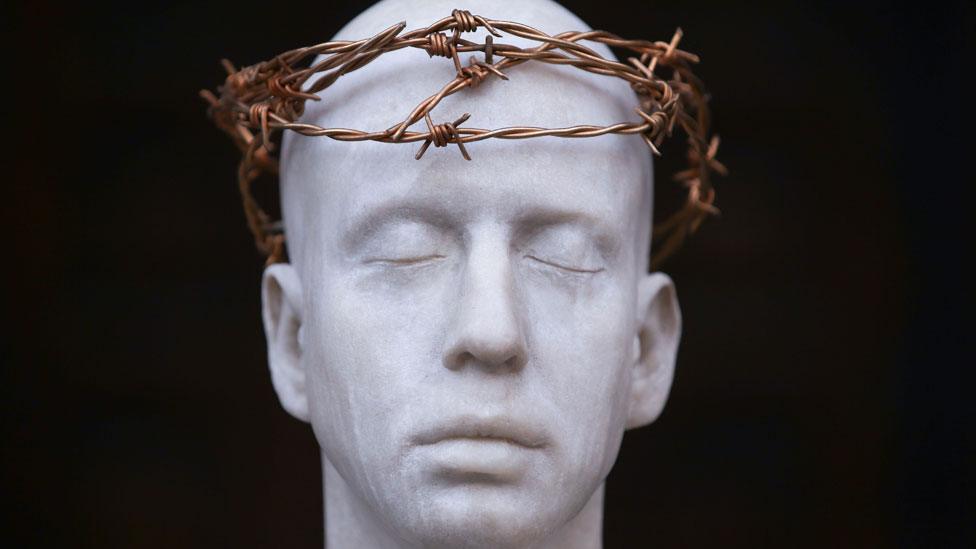

The statue, Ecce Homo, was originally on display on the fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square

When his sculpture, Ecce Homo, became the first to occupy the empty plinth in Trafalgar Square, he said: "I kept away from there for about three months, because I felt so self-conscious.

"And then when I did go there finally, I bumped into three people separately, and it looked like I was always hanging around there."

If he had to explain why he had kept creating: "It's something I absolutely love. It's just the love of art, being fascinated and beguiled and awestruck by a lot of painting.

"I managed to keep the hope alive long enough."