The 200-year-old diary that's rewriting gay history

- Published

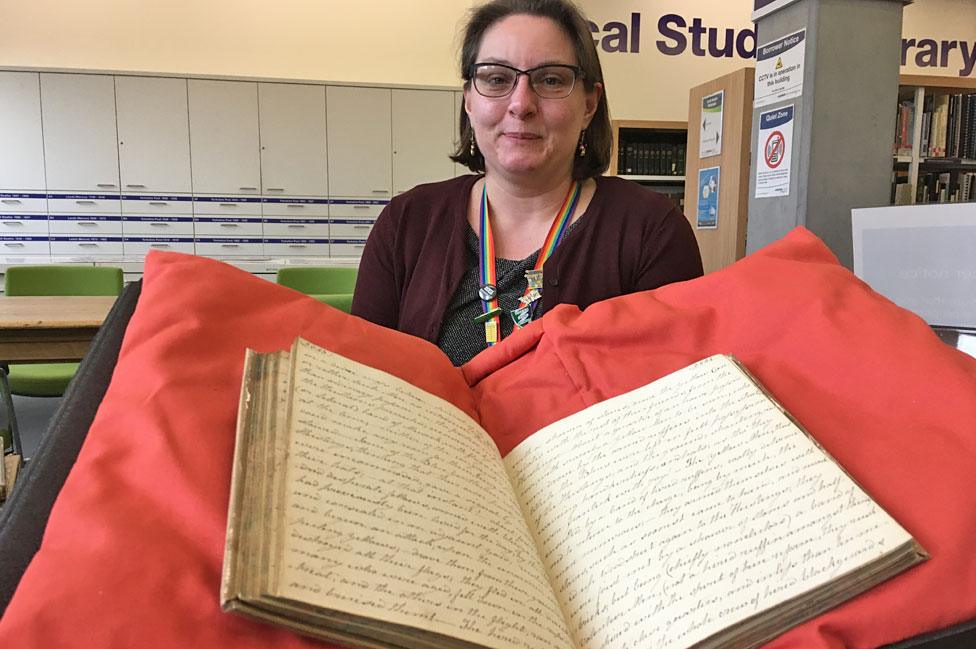

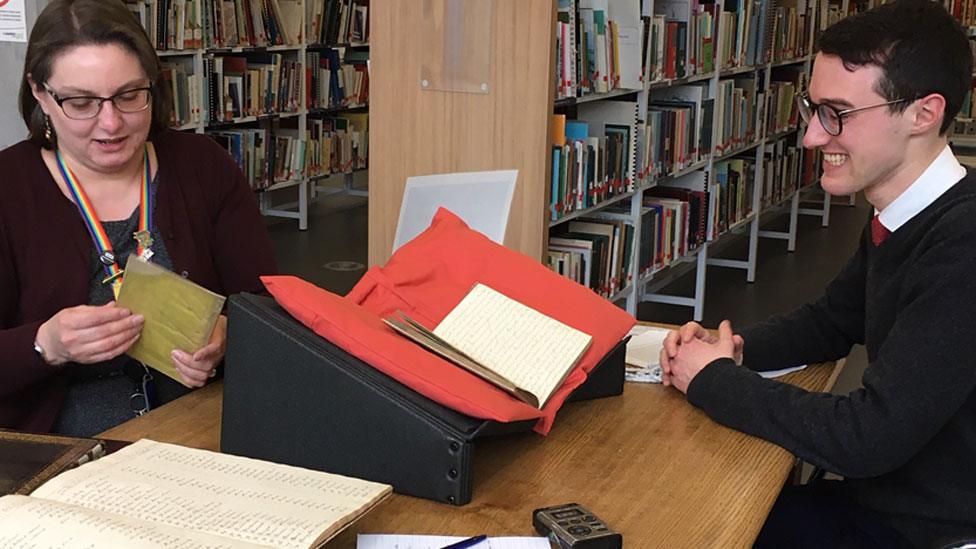

Claire Pickering in Wakefield library imagines the diary writer speaking in a Yorkshire accent

A diary written by a Yorkshire farmer more than 200 years ago is being hailed as providing remarkable evidence of tolerance towards homosexuality in Britain much earlier than previously imagined.

Historians from Oxford University have been taken aback to discover that Matthew Tomlinson's diary from 1810 contains such open-minded views about same-sex attraction being a "natural" human tendency.

The diary challenges preconceptions about what "ordinary people" thought about homosexuality - showing there was a debate about whether someone really should be discriminated against for their sexuality.

"In this exciting new discovery, we see a Yorkshire farmer arguing that homosexuality is innate and something that shouldn't be punished by death," says Oxford researcher Eamonn O'Keeffe.

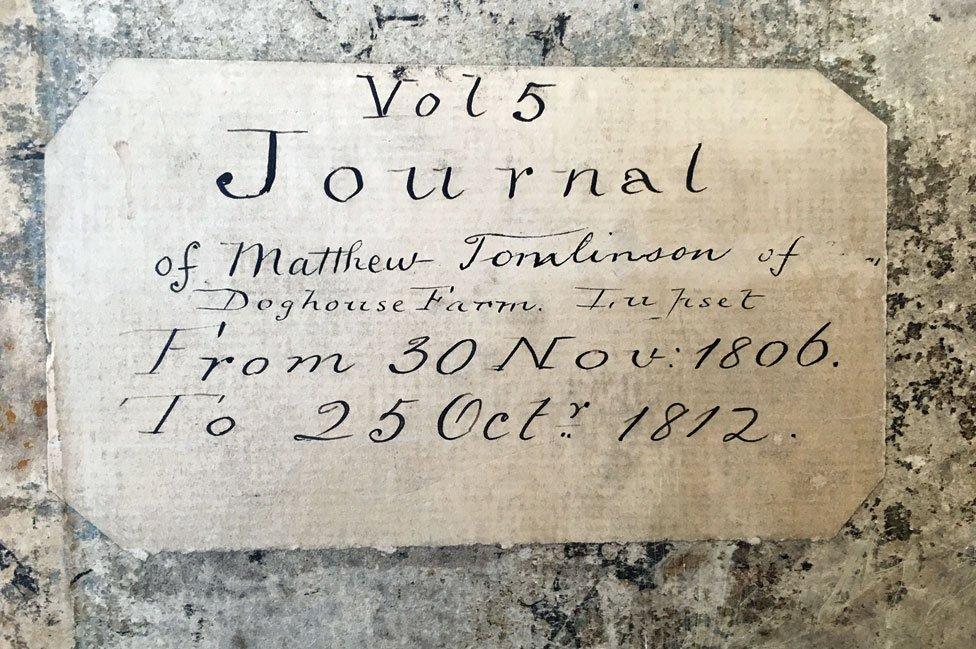

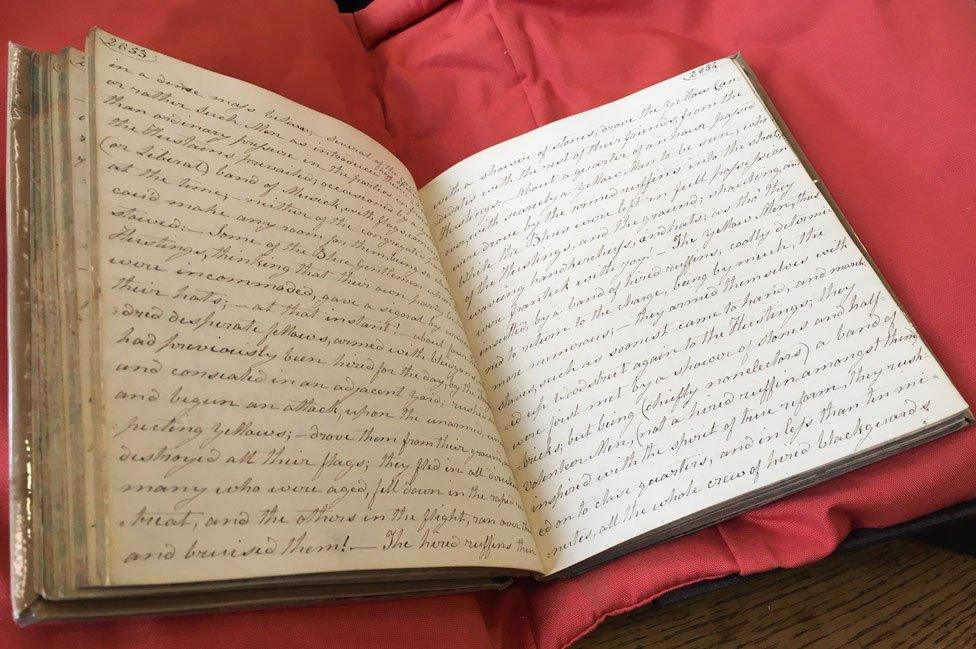

The diaries were handwritten by Tomlinson in the farmhouse where he lived and worked

The historian had been examining Tomlinson's handwritten diaries, which have been stored in Wakefield Library since the 1950s.

The thousands of pages of the private journals have never been transcribed and previously used by researchers interested in Tomlinson's eye-witness accounts of elections in Yorkshire and the Luddites smashing up machinery.

But O'Keeffe came across what seemed, for the era of George III, to be a rather startling set of arguments about same-sex relationships.

Tomlinson had been prompted by what had been a big sex scandal of the day - in which a well-respected naval surgeon had been found to be engaging in homosexual acts.

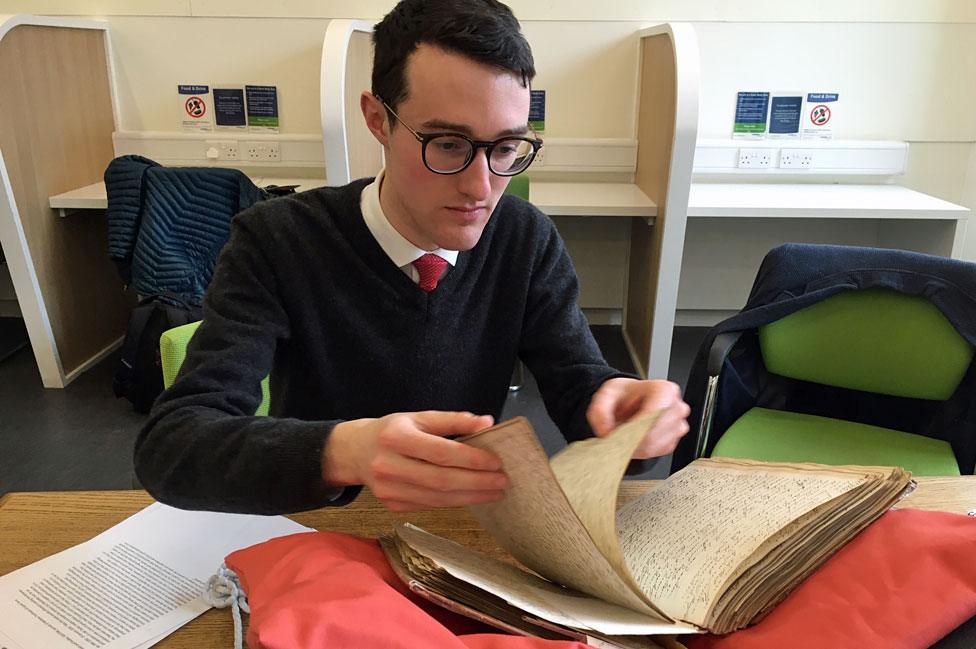

Historian Eamonn O'Keeffe says the diaries provide a rare insight into the views of "ordinary people" in the early 1800s

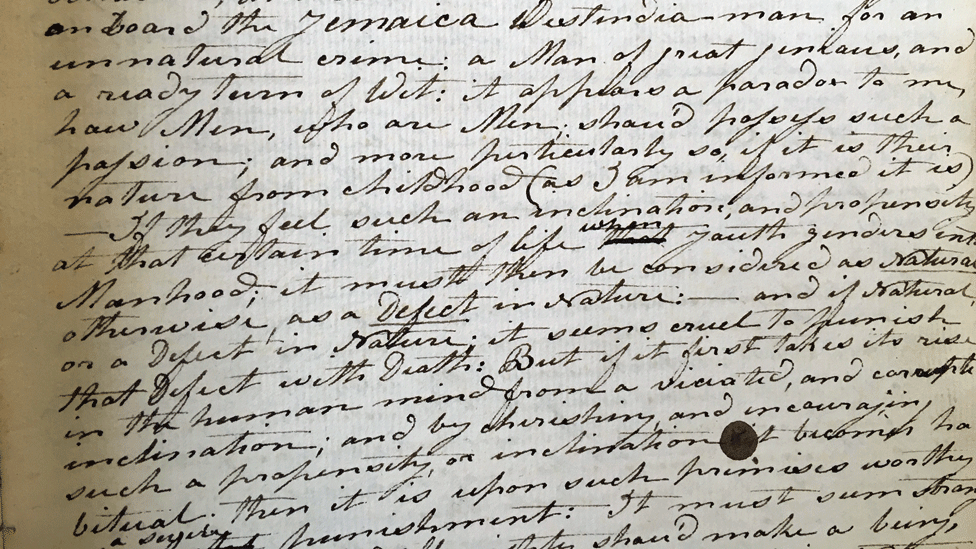

A court martial had ordered him to be hanged - but Tomlinson seemed unconvinced by the decision, questioning whether what the papers called an "unnatural act" was really that unnatural.

Tomlinson argued, from a religious perspective, that punishing someone for how they were created was equivalent to saying that there was something wrong with the Creator.

"It must seem strange indeed that God Almighty should make a being with such a nature, or such a defect in nature; and at the same time make a decree that if that being whom he had formed, should at any time follow the dictates of that Nature, with which he was formed, he should be punished with death," he wrote on January 14 1810.

If there was an "inclination and propensity" for someone to be homosexual from an early age, he wrote, "it must then be considered as natural, otherwise as a defect in nature - and if natural, or a defect in nature; it seems cruel to punish that defect with death".

The diarist makes reference to being informed by others that homosexuality is apparent from an early age - suggesting that Tomlinson and his social circle had been talking about this case and discussing something that was not unknown to them.

Around this time, and also in West Yorkshire, a local landowner, Anne Lister, was writing a coded diary about her lesbian relationships - with her story told in the television series, Gentleman Jack.

But knowing what "ordinary people" really thought about such behaviour is always difficult - not least because the loudest surviving voices are usually the wealthy and powerful.

What has excited academics is the chance to eavesdrop on an everyday farmer thinking aloud in his diary.

Tomlinson was appalled by the levels of corruption during elections

"What's striking is that he's an ordinary guy, he's not a member of the bohemian circles or an intellectual," says O'Keeffe, a doctoral student in Oxford's history faculty.

An acceptance of homosexuality might have been expressed privately in aristocratic or philosophically radical circles - but this was being discussed by a rural worker.

"It shows opinions of people in the past were not as monolithic as we might think," says O'Keeffe, who is originally from Canada.

"Even though this was a time of persecution and intolerance towards same-sex relationships, here's an ordinary person who is swimming against the current and sees what he reads in the paper and questions those assumptions."

Claire Pickering, library manager in Wakefield, says she imagines the single-minded Tomlinson speaking the words with a Yorkshire accent.

There are three volumes of Tomlinson's diaries at Wakefield Library

He was a man with a "hungry mind", she says, someone who listened to a lot of people's opinions before forming his own conclusions.

The diary, presumably compiled after a hard day's work, was his way of being a writer and commentator when otherwise "that wasn't his station in life", she says.

O'Keeffe says it shows ideas were "percolating through British society much earlier and more widely than we'd expect" - with the diary working through the debates that Tomlinson might have been having with his neighbours.

But these were still far from modern liberal views - and O'Keeffe says they can be extremely "jarring" arguments.

If someone was homosexual by choice, rather than by nature, Tomlinson was ready to consider that they should still be punished - proposing castration as a more moderate option than the death penalty.

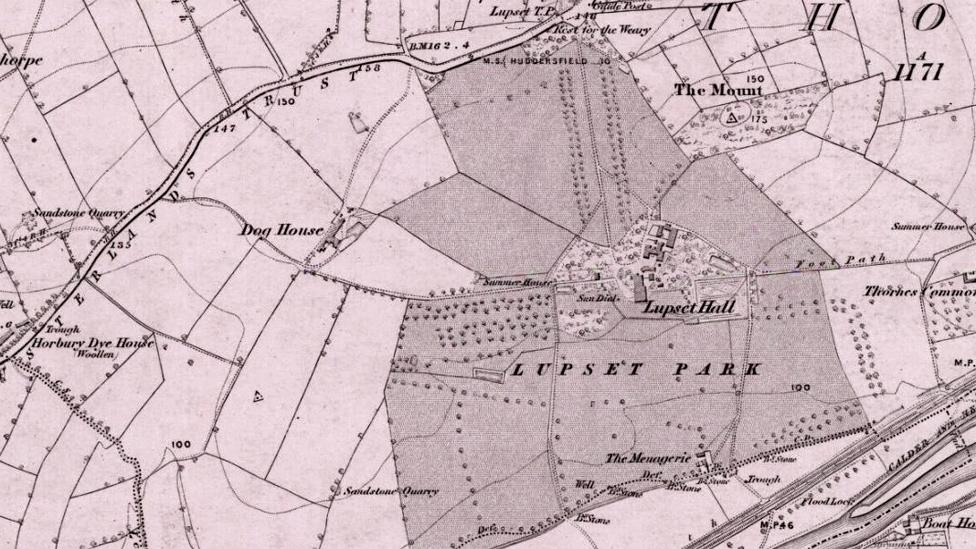

Tomlinson's former home was still there in the 1930s (bottom left), but has since disappeared beneath housing and a golf course

O'Keeffe says discovering evidence of these kinds of debate has both "enriched and complicated" what we know about public opinion in this pre-Victorian era.

The diary is raising international interest.

Prof Fara Dabhoiwala, from Princeton University in the US, an expert in the history of attitudes towards sexuality, describes it as "vivid proof" that "historical attitudes to same-sex behaviour could be more sympathetic than is usually presumed".

Instead of seeing homosexuality as a "horrible perversion", Prof Dabholwala says the record showed a farmer in 1810 could see it as a "natural, divinely ordained human quality".

Rictor Norton, an expert in gay history, said there had been earlier arguments defending homosexuality as natural - but these were more likely to be from philosophers than farmers.

"It is extraordinary to find an ordinary, casual observer in 1810 seriously considering the possibility that sexuality is innate and making arguments for decriminalisation," says Dr Norton.

Who was the writer of this diary?

Matthew Tomlinson was a widower, in his 40s when he wrote his journal in 1810 - a man of a "middling" class, not a poor labourer but not rich enough to own his own land.

"I try and imagine how he would have looked," says library manager Ms Pickering.

There are no pictures of Tomlinson, who is thought to have lived between about 1770 and 1850.

"Very dour," she suggests. And a "bit of a hypochondriac".

There are thousands of pages of handwritten journals - but some volumes appear to have been lost

"I imagine if you stopped him at his gate for a chat he'd talk about his gout more than anything else.

"I'd love to have a conversation with him about what Wakefield was like at the time," she says.

No-one knows how these private diaries, covering 1806 to 1839, ended up in Wakefield Library, but they were there by the 1950s and are presumed to be part of an earlier acquisition of old books and local documents.

There are three surviving volumes and at least another eight are missing.

But they show vivid detail about life in Wakefield in the early 19th Century.

Tomlinson, from his home at Doghouse Farm, recorded the life of nearby Wakefield

During elections, Tomlinson was appalled by the corruption, the rum drinkers having to be carried home in wheelbarrows and the "hired ruffians".

And at Queen Victoria's coronation he was sceptical about expensive ceremonies and celebrations, calling them all "humbug".

This was not a closed world. His social circle seemed to be avid readers of books and newspapers, following reports of revolutions abroad and riots and insurrections at home.

They saw elephants marching through Wakefield in a circus parade and military bands who had competed to hire the most talented black musicians.

We know where he lived - Doghouse Farm in Lupset, because he carefully wrote it on the front of his journals.

The farm, at the edge of the landowner's estate, is now under a housing estate and a golf course. All that survives are his diaries.

Tomlinson records a number of observations about his home city of Wakefield