Belsen 1945: Remembering the medical students who saved lives

- Published

Students from Guy's hospital just before they left for Belsen

"It deeply affected him and his trust in human nature," says Anne Stephenson of her father John Reynolds, one of 95 London medical students who arrived at the notorious Belsen concentration camp in May 1945 to help care for survivors wracked by disease and starvation.

The camp had been captured on 15 April by British troops who had no idea of the horrors they would find inside when the first tank pushed open the gates.

For the BBC's Richard Dimbleby, the first broadcaster to enter the camp, it was "the world of a nightmare".

About 10,000 dead bodies lay unburied, sanitation was non-existent.

There were 43,000 prisoners still alive, about two-thirds of them women, many so weak from starvation and disease they were unable to move from the huts where they were held and they were dying at a rate of about 500 a day.

The medical students, average age 21, were volunteers, recruited initially to help care for starving Dutch children but who found, just before they were due to travel, their destination had been changed to Belsen.

By the time they arrived at the beginning of May, most of the bodies had been removed but thousands of sick and dying people still languished in the huts.

"People in all stages of disease. Many were dead. Practically all were emaciated," John Reynolds, then a 23-year-old student at St Thomas's medical school, wrote later.

"Nearly all the internees had violent colic or diarrhoea."

They were suffering from a range of diseases including cholera, typhus, tuberculosis, sores, boils and gangrene.

"The people themselves were, on the whole, hopelessly filthy with no sense of decency or pride in themselves, treating the dead as furniture and their beds as latrines."

He carried these experiences with him for the rest of his life, says Anne, herself a doctor and a member of the academic staff at King's College London Medical School of which St Thomas's is now part.

"I remember once, we were all sitting having dinner and he suddenly said: 'I remember a blonde woman and they shot her in the leg. They shot her in the leg.'

"He had post-traumatic stress disorder, honestly. He had terrible PTSD that was never treated."

John Reynolds, on the far right of the middle row, was in the third year of medical school

Led by senior military medical staff, the students helped halve the death rate within a month.

It tested both their medical skills and their personal stamina to an unimaginable degree, according to Westminster student Michael Hargrave, in his diary.

A major puzzle was what to feed the internees.

British army rations were indigestible to starving people and could kill them, a concoction called Bengal Famine Mix, was unpalatably sweet, and intravenous feeding threw some, who feared fatal injections, into panic.

Ultimately, diluted soup and glucose drinks worked best.

Deaths overnight

In pairs, the medical students were allocated to huts where each morning they would separate the living from those who had died overnight.

"The bodies are dragged out by those who can walk and then the Wehrmacht load them on to massive lorry trailers, guarded all the while, and bury them in immense graves," wrote Guy's student John Kilby in a letter to his mother.

Those needing medical help were gradually transferred to a makeshift hospital for 7,000 housed in a military barracks camp.

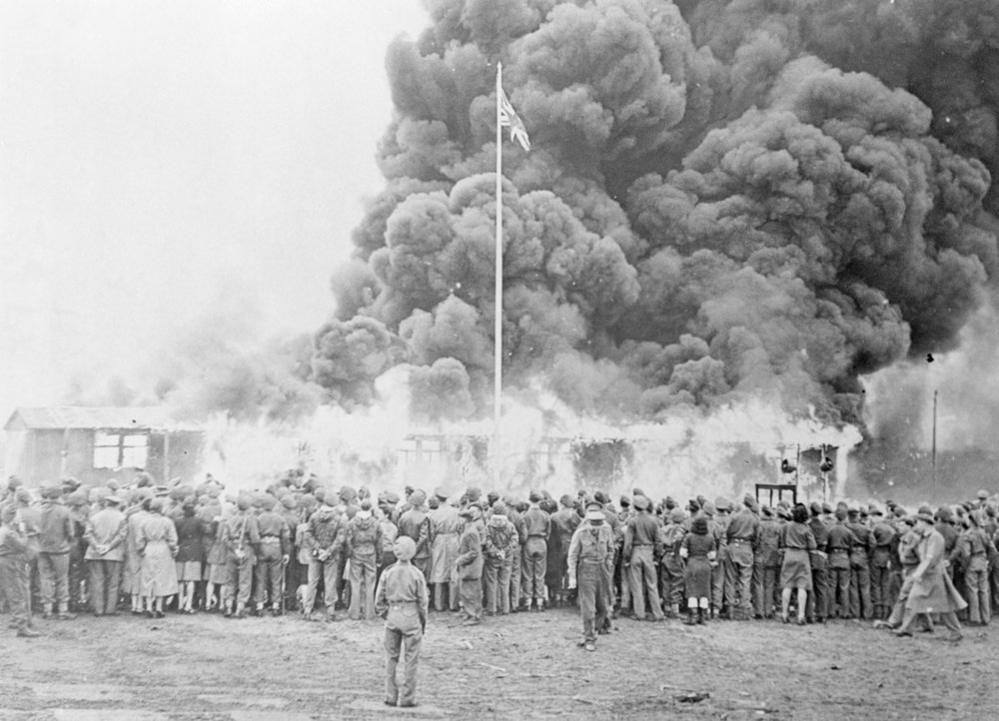

John Reynolds recounts how the huts were burned down one-by-one until only one was left.

On 21 May 1945 "an official ceremony of the burning of this last hut was attended by all those who worked in the camp... a volley was fired, the Union Jack unfurled and then the hut was burned to the ground by flamethrowers."

The last hut was burned down on 21 May 1945

A week later, the students' month at Belsen was over and they were sent back to their medical schools.

"These days, of course, you would have a debrief and you'd have post-traumatic stress disorder counselling," says Prof Stephen Challacombe, a professor of oral medicine at King's and a medical historian.

"It was so stark, just, 'Give up your uniforms, you're back in civilian life'."

Of the 95, despite being inoculated, two returned with tuberculosis and seven with typhus.

DDT was used liberally to kill lice and Anne Stephenson says her father always wondered whether the cancers he suffered in later life were connected with the pesticide.

In their later careers as doctors and academics "all the reports, to a person, talk about how magnificent they were", says Prof Challacombe who has delivered a series of lectures on their story.

This year, to mark the 75th anniversary of their endeavour, King's College Medical School, which, as well as St Thomas's, also includes Guy's, and accounts for 34 of the 95 students, is erecting plaques to their memory.

"When they were asked to go, they could never have imagined what they would walk into and do," says Prof Challacombe,

Sometimes audience members bring their parents' letters and diaries from the period, among them Gilly Kenny and Jenny Meade whose fathers, John and Bernard, were among the King's College contingent and remained lifelong friends.

Gilly says it was after her father's death when "we had to clear out all sorts of papers and we came across some that related to his time in Belsen... that it became a bit clearer".

She found the lecture "very emotional... I learned a lot".

Gilly Kenny (L) and Jenny Meade hand documents to Prof Challacombe

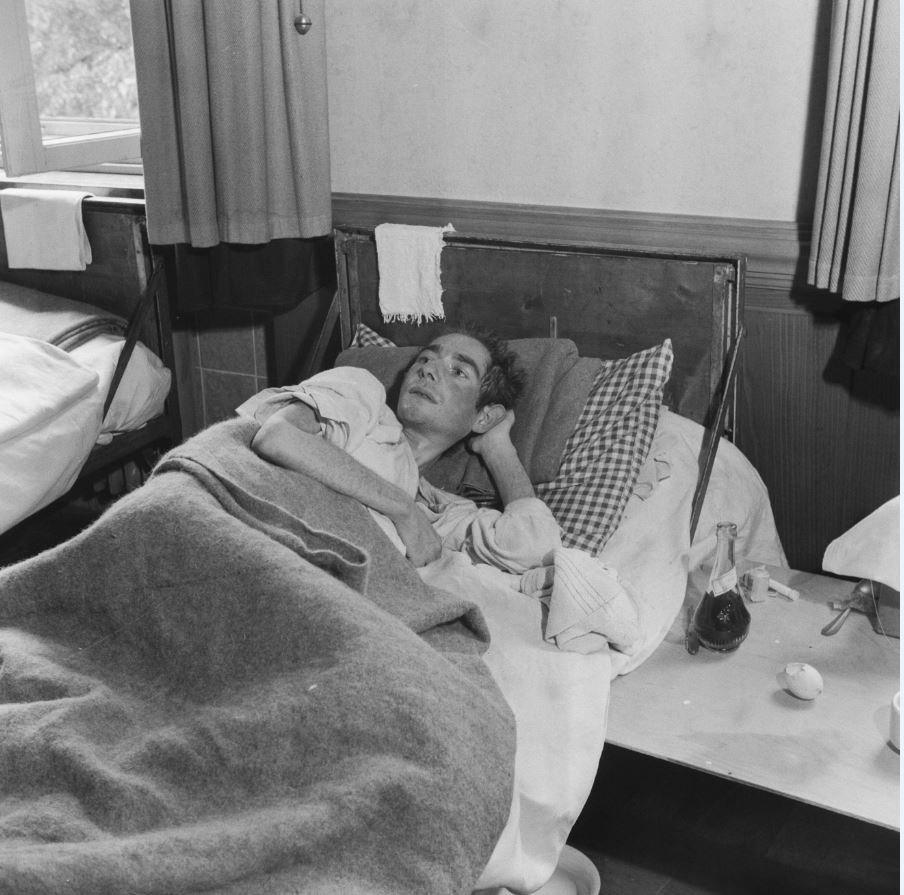

Prof Challacombe believes the most difficult time for the students was when the patients were transferred from the huts into the hospital.

"There is a point at which numbers and bodies turn into real people... suddenly individuals in beds as opposed to a mass of individuals lying on a floor...

"They did feel it when those patients that they'd been looking after, trying so hard, then died, I think that would have affected them."

He hopes modern day medical students will take a message from the story.

"I think understanding their sacrifice, understanding their willingness to get involved and to contribute is a real hallmark of medicine.

"I think there's a lesson for me in helping people to understand you can attain those pinnacles and you can contribute, everybody can contribute however insecure they feel at the time."