Universities told to keep places open for A-level appeals

- Published

Universities in England are being told to keep places open for students if they appeal against A-level results.

Amid uncertainty about replacement exam grades, Universities Minister Michelle Donelan has urged university heads to be as "flexible as possible".

It means if students miss the required grades but successfully appeal, they could still start next term.

"Nobody should have to put their future on hold because of the virus," said Ms Donelan.

With A-levels cancelled because of the coronavirus pandemic, students will receive estimated results on Thursday, which will be used to decide university places.

But if students get disappointing results that they think are unfair, universities are being told to leave the door open for places until appeals have been considered by exam boards.

Appeals, which have to be submitted through schools, should be completed by 7 September, allowing students who get improved grades to take up places this autumn.

The biggest factors determining the replacement exam grades will be how students are ranked in ability and the previous exam results of their school or college.

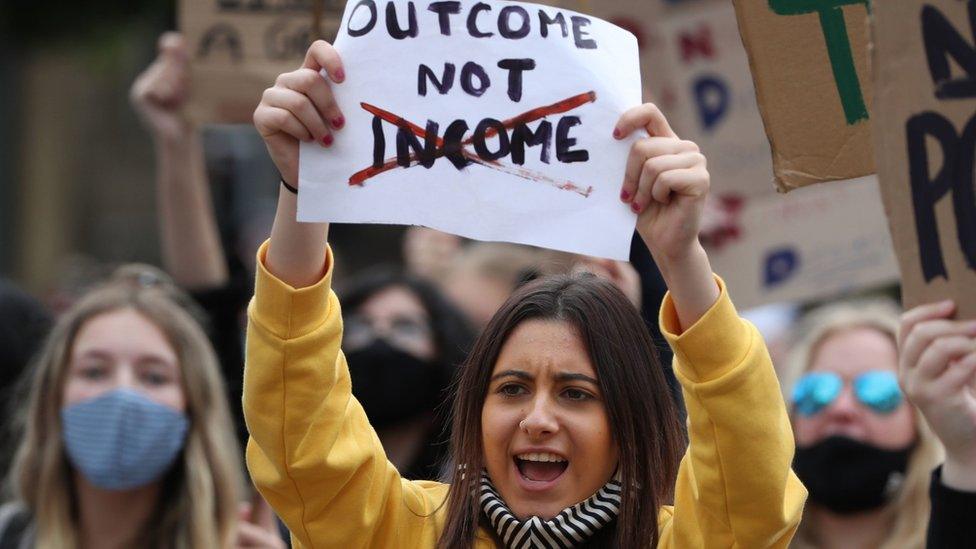

Protests in Scotland criticised how estimated results were pegged to schools' previous results

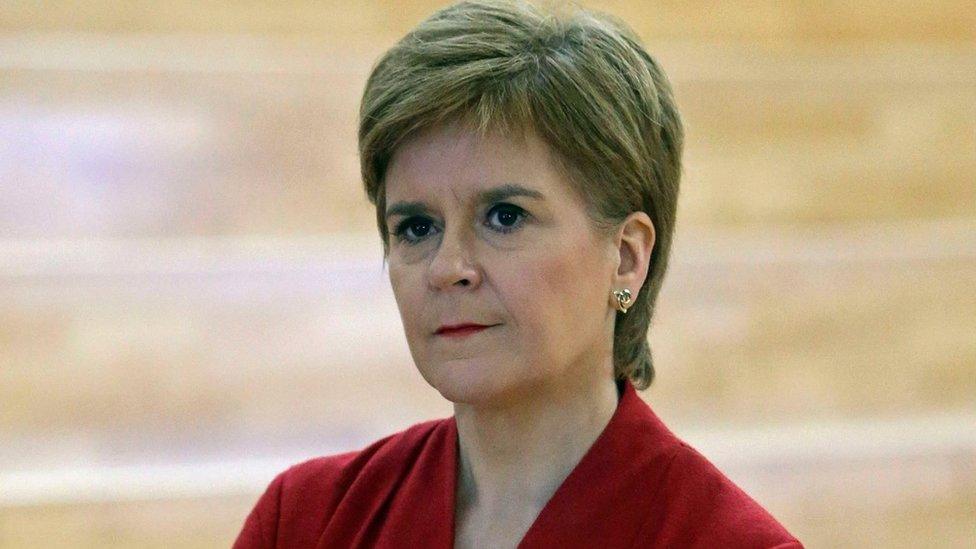

As the row over Scottish exam results has shown, this can mean that high-achieving youngsters in schools with poor results can be marked down.

Scotland's First Minister Nicola Sturgeon apologised on Monday after accepting her government "did not get it right" over exam results.

Education Secretary John Swinney will set out the Scottish government's plan to fix the issue later.

Ms Donelan said she recognised the need for universities to be fair towards "students who are highly talented in schools or colleges that have not in the past had strong results".

She said the "vast majority of grades" were expected to be accurate, but added it was "essential" to have the appeals "safety net" for "young people who may otherwise be held back from moving on to their chosen route".

Calling on universities to show "flexibility" in admissions decisions, she called on them to hold the places of students whose "grade may change as the result of an appeal".

But despite these concerns - and the change of heart in Scotland - there are no signs of any change in using a similar approach to moderating results in England.

This is still expected to be a good year for applicants, with an expected reduction in overseas students meaning that universities will have more places to fill.

A-level results are going to be higher this year - but not by as much as teachers' predicted

The exam regulator Ofqual has already said there will be a more lenient approach to grades this year, with a two-percentage-points increase expected in top grades at A-level.

But results will not be as generous as teachers' predictions, which would have pushed up results by 12 percentage points - with these predictions able to be shared with pupils after the results are published.

The results to be issued this week are designed to maintain continuity with previous years, but there have been concerns about whether individual students could be treated unfairly.

A survey of 500 A-level students in England, carried out by the University of Birmingham and the University of Nottingham, suggested almost twice as many students would have preferred to have taken their exams, rather than rely on estimated grades.

Education Secretary Gavin Williamson defended the system for calculating grades this year as "fundamentally a fair one".

"We know that, without exams, even the best system is not perfect," he said.

"That is why I welcome the fact that Ofqual has introduced a robust appeal system, so every single student can be treated fairly - and today we are asking universities to do their part to ensure every young person can progress to the destination they deserve."

But Larissa Kennedy, president of the National Union of Students, said there was "absolutely no merit" in looking at schools' prior overall performance to judge students' results this year, criticising it as "baking inequality into the system".

She told BBC Newsnight: "They're just trying to fit students' attainment against a prior year, which means you're just assuming and reproducing the fact that students from low socio-economic backgrounds are - as this system would say - due to get lower grades."

She described the algorithm being used to determine grades as a "lazy move", leading to "individuals being let down by an unjust system", which she said was "completely wrong".

- Published10 August 2020

- Published21 July 2020