What's next in the arguments over exam results?

- Published

In any other year the headlines for these A-level results would have been about the highest ever number of top A* and A grades.

There would probably have been some sniping about grade inflation - with almost 28% getting top grades in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, and overtaking the previous record of 27%.

These were the best A-level top scores since the exams began almost 70 years ago.

But instead - in this strangest of years, when the results are for exams that were never taken - the stories are about confusion and discontent about these estimated results.

It was more flat beer than a champagne moment.

Even though results have gone up, confidence in how they were calculated seems to have gone down.

So what happens next?

Much of the focus has been on the downgrading of about 40% of entries from what teachers had predicted.

This was the year of the results without any exams being taken

And over the next few days education ministers and watchdogs will be under intense scrutiny over whether this downgrading been fairly shared?

The estimated results in England, Wales and Northern Ireland have been linked to how well schools have performed in the past.

And the screeching u-turn in Scotland was because this was found to exaggerate inequalities - and threatened to drag down clever pupils in low-achieving schools, trapping them in the disadvantage of their postcode.

The exam boards say that there is no bias in the A-level results, whether on grounds of deprivation, gender or ethnicity.

But tug a little harder and gaps appear. Independent schools increased their A*s and A grades by five percentage points - it was only two percentage points in comprehensives and 0.3 percentage points in further education colleges.

The biggest drop in grades between teachers' predictions and the estimated grades was among the poorest students.

Not by a huge margin, but every grade could make a big difference to someone's future.

There is good news and bad news every year from exam results. But perhaps what fuelled the anger this year has been the sense of powerlessness. An impersonal algorithm, over which they have no real control, might have ruined a deeply personal ambition.

And it revolves around a system which was anchored to the past performance of a school, rather than for instance, the past performance of an individual.

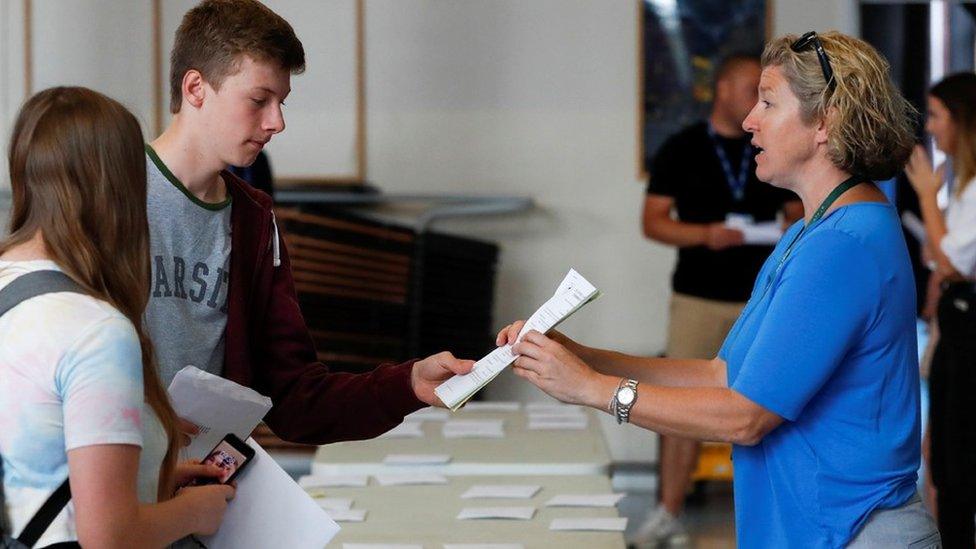

Students at Crossley Heath Grammar School in Halifax receive their results

Although teachers were asked to submit individual predicted grades, in the end it was the ranking order of pupils combined with past performance, that were the keys to deciding the outcome.

Head teachers are already mobilising for a rethink - but it remains uncertain whether pressure will build for this in the way that forced changes in Scotland.

Head teachers' union leader Geoff Barton has warned of pupils facing grades that have been lowered in a way that has been "unfathomable and unfair".

And a snap poll of independent school heads - whose schools overall have improved results - showed 81% thought the system for deciding results was unfair.

The counter argument will be that there is no point making a change that will create even more unfairness elsewhere.

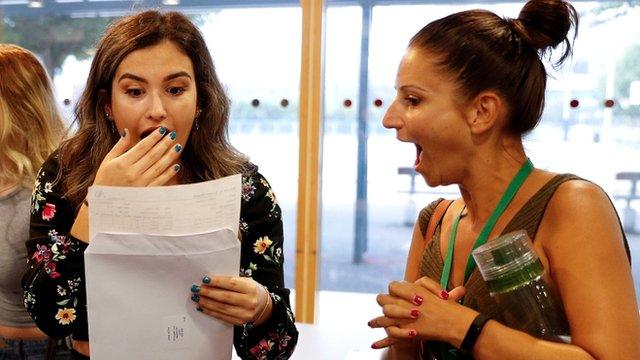

Brenda Irabor from Ark Academy in Brixton, south London, achieved three A* grades

England's exam watchdog has warned that if teachers' predictions were used it would have meant 38% of grades being A*s and As.

What would happen if some schools had been scrupulous in their predictions while others had been much more optimistic?

And the aim of the temporary arrangements, to allow young people to progress with their education despite the pandemic, has seen rising numbers of disadvantaged youngsters heading to university.

The next big challenge in this controversy will be what happens to those who feel they have been treated unfairly.

The pressure release valve has been the offer of appeals and second chances. But these promises still lack much detail.

For instance, how will the autumn written exams really operate? Those picking up their A-level results have left school, they have been out of the classroom since March, what papers are they really going to be taking in a couple of months and who will teach them?

Another tricky question will be how appeals based on higher mock exams will be decided. This was so last minute that it was announced before the watchdog had been able to decide the rules.

In the next few days they will have to say what constitutes a "valid" mock exam that will be enough to overturn an A-level grade. And what will happen if many schools apply for changes for large number of their pupils?

Such options for challenging results mean this year's results still have a long way to go - both for disappointed students and for politicians arguing about what it means.

It also means another strange moment from this year. People are actually nostalgic for the stress and revision that comes with real exams.