Parents get advice for first-day nerves at school

- Published

- comments

It's more than 160 days since schools sent home pupils at the beginning of the lockdown. No-one at the time, in those bewildering March days, could have known when children would return.

The leaves that were starting to appear on the trees when children hurried home are now about to turn brown. It's been a long and strange summer.

Exams were cancelled and there were replacement results. And then those results were cancelled too. There was constant confusion over whether or not pupils were going back to school.

Home-schooling didn't always really happen and rites of passage such as leaving events had to be called off. There were more u-turns than a handwriting text book.

Many pupils will not have been to school since they were brought home in March

But children are now going back full-time for the new school year. The "new normal" became a lockdown cliche, but going back to school in September is a rare case of the old normal.

So what's it going to be like for these returning pupils? What should parents be saying to them? Are they going to be able to get back to learning after months of lie-ins and Netflix?

"I think there's a real need to recognise the physical, mental and emotional impact of going back," says leading educational psychologist, Daniel O'Hare.

Children are likely to be "drained" by the sudden "overload" of being in school after being cocooned at home for so long, says Dr O'Hare, joint chair-elect of the British Psychological Society's education and child psychology division.

"It will be very new to go back into that full-on setting with 30 children in a class," he says.

What makes it more complicated, says Dr O'Hare, is that the lockdown has been experienced by families in such different ways.

School dinners will be back on the menu as the new term starts

For some children, there will have been worries about their families catching the virus, or facing pressures over money, insecure jobs and lack of space.

"But on the other hand, there will be a population of children who have experienced lockdown as very positive," says Dr O'Hare.

They will not have had the stresses of school and they might have enjoyed spending more time together with their parents.

The lockdown saw a temporary reinvention of family life, with those parents working from home seeing more of their children than would ever usually be possible. When this finishes, children and perhaps also their parents could miss this closeness.

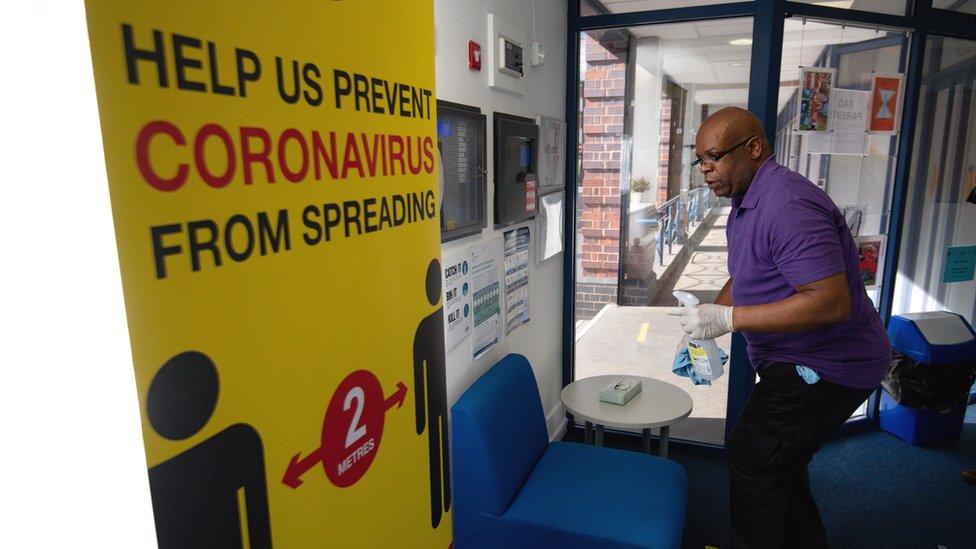

Schools have been getting their safety plans ready for when pupils return

Dr O'Hare says it would be a misunderstanding to think this follows socio-economic lines, with middle class families having had a better time during the lockdown.

"We have spoken to children from disadvantaged families and they said that they really enjoyed spending so much time with mum and they loved playing games and that it was better than before," he said.

"You know there's a real mix of stories coming from children about going back to school."

It means many different, contradictory responses which schools will have to address.

Some researchers have warned of increased mental health worries while at the same time others have said teenagers' anxiety levels have gone down during the pandemic.

"Children have missed school and all of the social benefits that it brings," says Dr O'Hare, who works with the local education authority in Gloucestershire and at the University of Bristol.

For children who have "challenging home circumstances", he says there might be a relief at being back at school.

But uncertainty also creates stress and the new school year could look very different.

What will it be like getting up for school after months of lie-ins and without a routine?

Dr O'Hare says parents can help to reduce anxiety by letting children know what changes to expect - how they will be in separate "bubbles", the one-way systems, the transport arrangements, the changes to timetables and the hand washing.

Another educational psychologist, Will Shield, based at the University of Exeter, says children should be told that it's "absolutely ok to be concerned" about going back and to talk about any particular worries.

"It is important that teachers and parents let pupils know it is perfectly normal to be concerned about being away from home or worried about learning they may have missed, alongside feeling excited and happy about returning to school," said Dr Shield.

Dr O'Hare says research shows children might be frightened of catching coronavirus and putting their family at risk.

Hand washing is going to be an important part of the new school routine

Friendship groups could have changed and there might be anxiety about falling behind with school work after so much missed time, he says,

The children's charity Barnardos has published research suggesting that 4% of children might try to refuse to return to school at all.

A survey for Netmums suggested a fifth of parents were still worried about the safety of going back to school, while a YouGov poll suggested about one in six parents was "seriously considering" keeping their children out of school.

But Dr O'Hare says not to predict or expect problems, because the biggest reaction might be about seeing friends again.

There was a first wave of school returns for primary pupils in June

"The conversation can also be positive. What are they looking forward to? Who are they looking forward to seeing? I think it's about trying to promote that sense of excitement," he says.

He recommends "watchful waiting - just being aware of the different reactions that children can have" and keeping talking to them about how they feel about going back.

"Because some children might seem fine and it's not until three or four weeks later that they have a massive outburst."

After a year without precedent, it seems appropriate the advice is not to make any assumptions about what happens next.

BACK TO SCHOOL: BBC Bitesize is here to help

AUTUMN TERM: What are this term's topics?