Coronavirus: The story of the big U-turn of the summer

- Published

A-level results day started terribly for Grace Kirman. The sixth former in Norwich had been waiting anxiously to hear whether she would get the grades needed for her dream university place.

But it was bad news and a rejection email had arrived. The grades produced by the exam algorithm had been lower than her teachers predicted - and the offer to study biochemistry at Oxford University was disappearing before her eyes.

"It wasn't my fault and it was really unfair," said the student from Notre Dame High School.

She'd worked extremely hard for her A-levels, it had been her big ambition, she'd been on a university outreach scheme for disadvantaged youngsters, and she'd been quietly confident of getting the A* and two A grades needed.

But this summer's exams had been cancelled by the Covid-19 pandemic - and England's exam watchdog Ofqual had produced an alternative way of calculating grades.

Her teachers had expected three A*s - but the algorithm produced results of three As. It might be a small margin for a statistician, but it was a difference that she said "could change her life".

"I was so disappointed, I knew I was equally intelligent," she said. And she was angry too at the way doors suddenly seemed to be closing.

Brian Conway, chief executive of the St John the Baptist academy trust responsible for the school, was beginning to see other inexplicable results arriving.

"The tragedy of results day was when people you would bet your house on getting a grade C were given a U grade," he said.

Something was going badly wrong - and the school decided to challenge the results, and in Grace's case, to get in touch with Oxford to try to overturn the rejection.

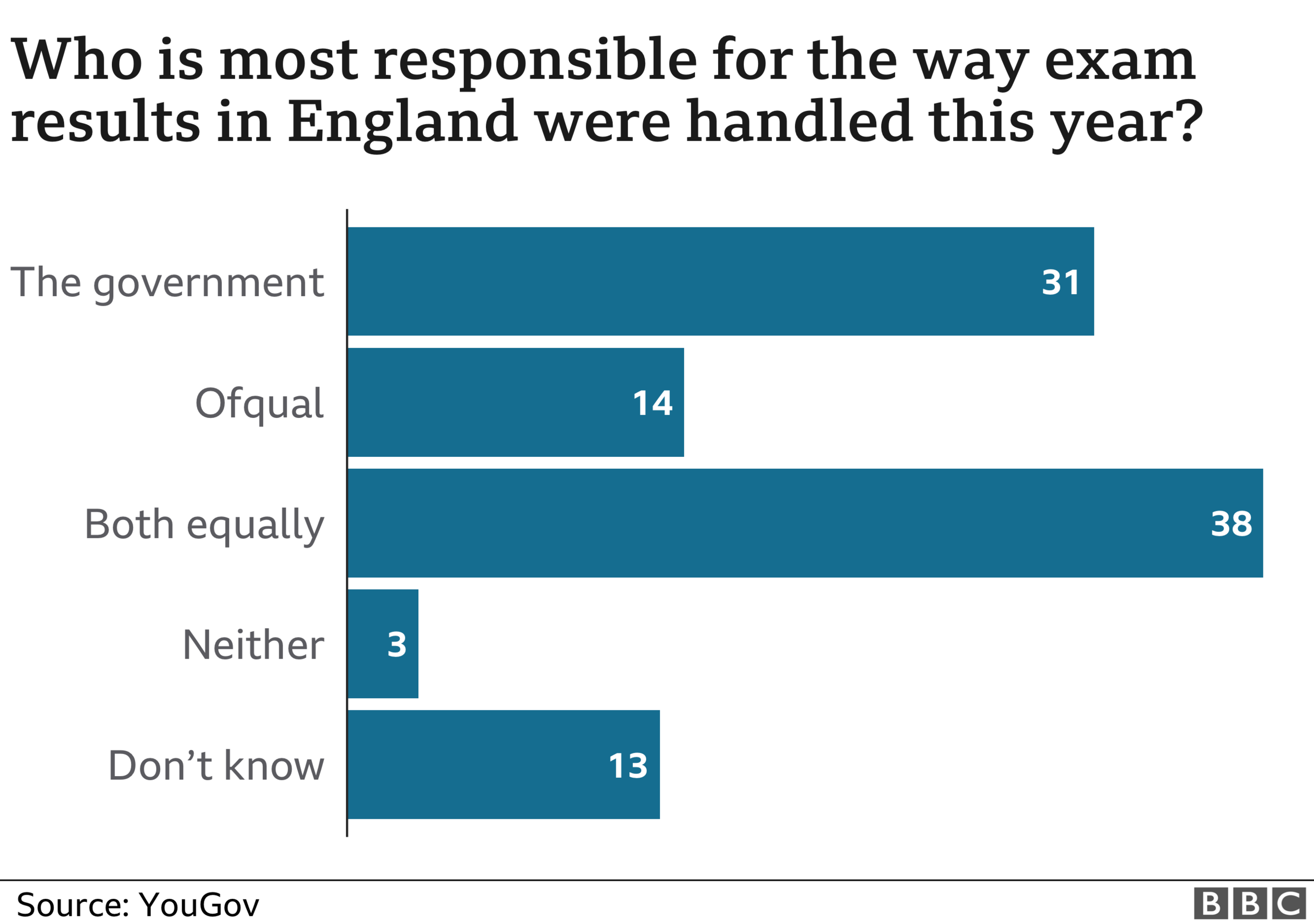

There were problems with exams across the UK this summer, but in England it's the Department for Education and Ofqual which will face public scrutiny to explain the confusion, the colossal U-turns and resignations.

The algorithm for replacement grades mostly relied on two key pieces of information - how pupils had been ranked in order of ability and the results of schools and colleges in previous years.

Of less influence were teachers' predictions and how individual pupils themselves had done in previous exams.

It was designed to stop grade inflation and in effect replicated the results of previous years - but it meant a serious risk of disadvantage for talented individuals in schools that had a history of low results.

It would be like being told you'd failed a driving test on the grounds that people from where you lived usually failed their driving test. That might be the case, but it's hard to take when you hadn't even started the car.

But if the aim was to keep grades in line with previous years, the opposite happened. There were stratospheric increases particularly at A-level - with more than half of students getting A*s and As in some subjects.

While the scrutiny will focus on what went wrong in past weeks, the bigger fallout could be from what it changes in the future. A major unintended consequence could be a radical shake-up of England's university admissions, with plans believed to be in the pipeline.

This summer has shown the problems with estimated grades - raising the issue of whether such predictions should still be used for university offers, rather than waiting until students have their actual results.

Schools Minister Nick Gibb this week described as "compelling" the argument made by former universities minister Chris Skidmore that the "entire admissions system to university should now be reformed". Also expect in the forthcoming months to hear some big questions about the future role of Ofqual.

England's Education Secretary Gavin Williamson, facing calls for his resignation over the exams fiasco, will have to defend himself in front of the Education Select Committee this week.

The committee's chairman, Robert Halfon, likened the exam problems to the Charge of the Light Brigade, where no-one, particularly Ofqual, seemed able to heed the warnings to stop.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who originally called the results "robust" and then blamed a "mutant algorithm", has accused critics of relying on "Captain Hindsight". But more evidence of foresight in warnings is emerging too.

Barnaby Lenon, chairman of the Independent Schools Council, told the BBC he had warned in stakeholder meetings with Ofqual about the dangers of attaching so much weight to schools' previous results, and so little to teachers' estimates. "It was always going to be a hashed job," he said.

He thinks Ofqual and the Department for Education had begun to prioritise sounding publicly confident rather than being open about the shortcomings. Mr Lenon, a former head teacher of Harrow School and former Ofqual board member, had made his concerns public.

On 7 July, at the Festival of Higher Education at the University of Buckingham, he predicted unreliability and unfairness in the results and warned Ofqual was being asked to do a "terrible thing" in producing these calculated grades.

SOCIAL DISTANCING: What are the rules now?

SUPPORT BUBBLES: What are they and who can be in yours?

FACE MASKS: When do I need to wear one?

TESTING: What tests are available?

Danger signals couldn't be dismissed as politically motivated. On 26 May, a warning was sent from the New Schools Network, which supports free schools and has strong ties to Conservative education policy.

The group's director Unity Howard, wrote to Sally Collier, the now resigned head of Ofqual, and to Gavin Williamson: "It is easy to bury these arrangements in scientific modelling, but the issues here will affect at least a generation of children, but more likely those that come after it too."

It included warnings from seven schools and trusts - and it's understood the group held a meeting with Ofqual.

The Northern Powerhouse, a lobby group for the north of England chaired by former Tory chancellor George Osborne, had also been flagging concerns about BTec vocational exams as well as A-levels and GCSEs.

Frank Norris, working with the Northern Powerhouse on education, told the BBC the "proposed algorithm design was always going to put the average performance of schools above individual merit".

With worries not allayed, the Northern Powerhouse wrote to Sally Collier on 9 August, drawing attention to their high level of concern about a disproportionate impact on poorer communities. On 11 July, the Education Select Committee pointed to unanswered questions about the fairness of how grades would be calculated.

Ofqual was not unaware of these worries, not least because the regulator says it was giving its own advice to ministers about the risks - and right to the top.

Julie Swan, Ofqual's executive director of general qualifications, said 10 Downing Street had been briefed on 7 August, highlighting risks over so-called "outlier students" - the bright pupils whose grades might be reduced because they were in low-performing schools.

There were also weekly meetings with education minister Nick Gibb. Kate Green, Labour's Shadow Education Secretary, said in the House of Commons this week the exam controversy had caused "huge distress to students and their parents" - and asked Mr Gibb why he had failed to respond to warnings. "These warnings were not ignored," said Mr Gibb. "Challenges that were made by individuals were raised with Ofqual and we were assured by the regulator that overall the model was fair," he told MPs. It was only when grades were published that "anomalies and injustices" became apparent, said Mr Gibb.

A common thread to the warnings was although the results might work smoothly in terms of national statistics, maintaining a similar pattern to previous years, this would be at the cost of individual unfairness. The standardisation process, which tended to push down teachers' grades, would also not apply to subjects with smaller numbers of entries, such as classics and modern languages - with accusations this would benefit independent schools.

Grace Kirman was one of these "anomalies" - her future hanging in the balance. But when had this year's exams really begun to go into tailspin? If you wanted to pinpoint a moment, it might be about 36 hours before Grace and hundreds of thousands of young people were finding out their results.

That was the heatwave night of Tuesday 11 August, ahead of A-level results being released on Thursday. In Scotland there had been a U-turn on grades, and pressure was building for a response in England.

When it came, it left Ofqual completely wrong-footed and unable to explain how it would work. The Department for Education had informed them of a major change that would allow schools to appeal over grades on the basis of their mock test results. It was announced late in the evening as an extra "safety net" and "triple lock", but was eventually ditched within the week.

But head teachers, who had been on a low-boil all summer, went into volcanic mode - attacking this last-minute change as "panicked and chaotic". This sudden rule change meant a school could appeal for an upgrade if a mock test had been higher than the calculated grade about to be issued.

This infuriated head teachers who said mocks were carried out in many different and inconsistent ways. Sometimes they had been deliberately marked down as a scare tactic and some schools had not taken them at all. Therefore, they said, they could not be used to decide such important results.

Heads' leader Geoff Barton said at that point he knew this approach to exams had become "unsustainable". It had been "fatally undermined" by an unworkable decision, which he said represented a "complete failure of leadership". Mr Halfon said it also raised the fundamental question about who was really in charge - and if Ofqual wasn't really acting independently, then what was its purpose?

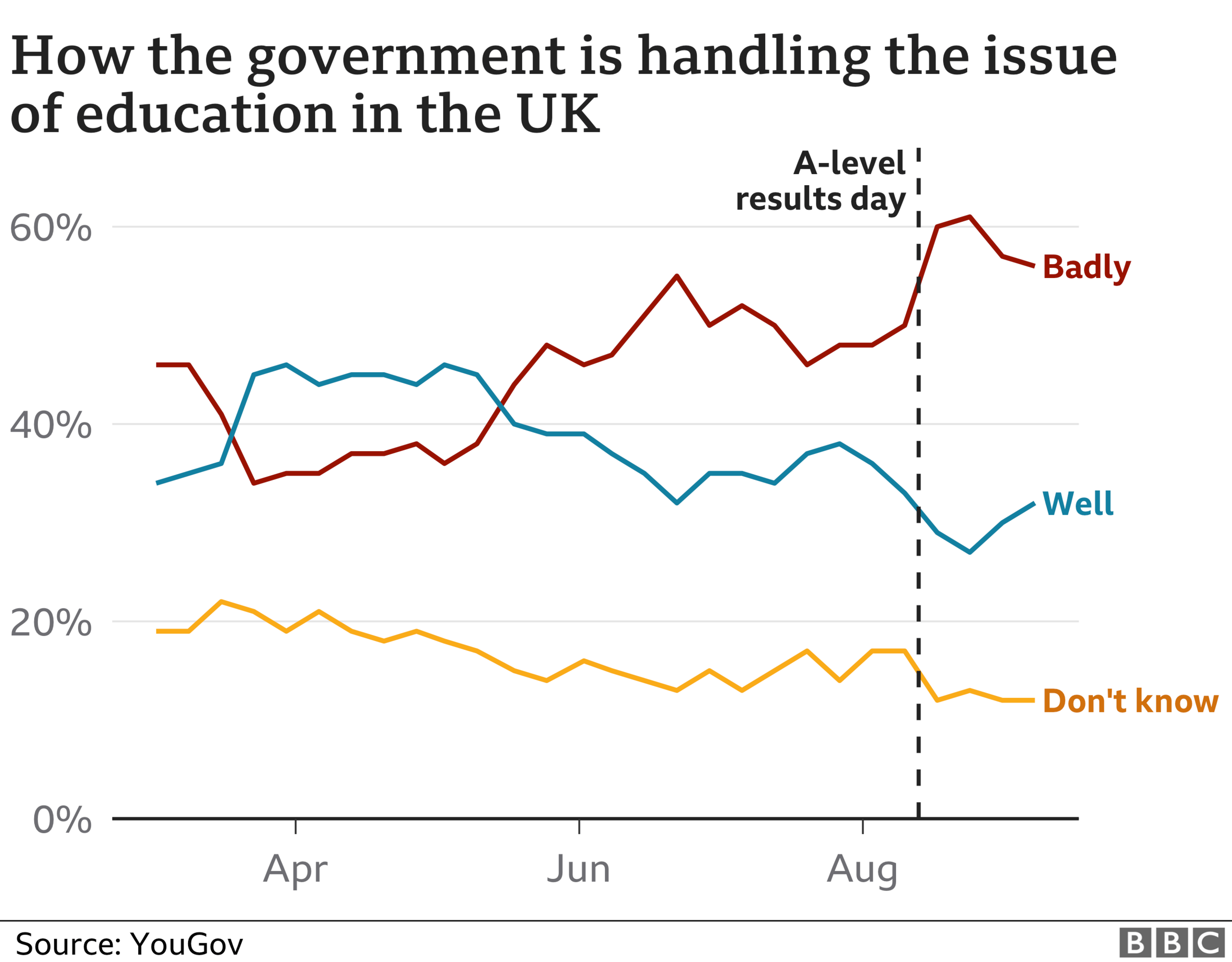

Results day on 13 August added to the confusion. These calculated grades produced the highest results in the history of A-levels - but in the background was a growing volume of protest over the algorithm reducing 40% of grades below teachers' predictions. MPs saw emails arriving in their in-trays, upset parents took to Twitter, lawyers warned of multiple legal challenges, universities didn't know if grades were going to be changed on appeal and marchers were waving placards demanding a U-turn.

On Saturday 15 August, matters became even more bizarre. Ofqual published plans for appeals over mock tests - but in the evening Gavin Williamson rang Sally Collier disagreeing with the guidance and it was taken down again from the website.

According to Ofqual chairman Roger Taylor, the situation was "rapidly going out of control" - and on Sunday the watchdog took the momentous decision to switch to centre assessed grades - the results estimated by schools.

This biggest U-turn of the summer was made public the next day and the education secretary told students he was "incredibly sorry".

Sally Collier, who has talked of her admiration for Edith Cavell, the nurse executed during the First World War, later stepped down as chief regulator and has made no comment since.

At the Department for Education, it was the senior civil servant, Jonathan Slater, who lost his job, with accusations that he had been "scapegoated". The blame game had begun almost immediately. Ofqual's argument has been they knew the risks of the iceberg ahead, but they had warned ministers and been told not to change direction.

The politicians in turn say they had heard the iceberg warnings, but Ofqual had assured them it would be safe. "The finger of blame is pointed at everyone else," says heads' leader Mr Barton.

What has baffled school leaders is why, with almost five months between the cancellation of exams and the issuing of calculated grades, there wasn't a more thorough attempt to test the reliability of results in advance, including with real schools. Ofqual's defence to all of this, according to Mr Halfon, could be summed up as: "Not me, guv."

There are also questions about the delays for results for BTec students - and MP Shabana Mahmood said it was disgraceful how they had been "left languishing at the back of the queue". There is another uncomfortable truth from the U-turn, which Barnaby Lenon said will have created a "different kind of injustice". Schools which were over-generous in their predictions will have got better grades than those which were more painstaking.

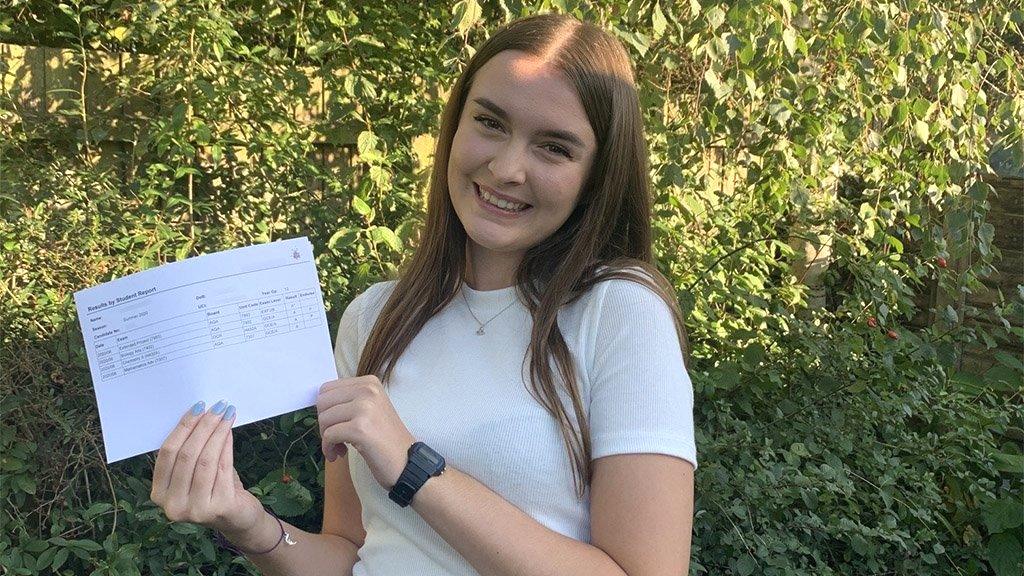

Things eventually turned out well for Grace

Mr Conway, leader of Notre Dame's academy trust where Grace was at school, said his staff had put a "huge effort" into making sure every estimated grade was accurate and evidence based - and carried out their own moderation process to guard against grade inflation. But there are persistent rumours of other exam centres which have ended up with implausibly high grades for many of their students.

Pupils could have unfairly been "bumped off" university places as a result, said Mr Lenon. When Mr Williamson faces the select committee this week he is likely to argue that no-one wanted to cancel exams, but the pandemic forced them to find an alternative - and when there were problems his department took swift action.

"It was not a decision that was taken lightly. It was taken only after serious discussions with a number of parties, including, in particular, the exam regulator, Ofqual," he told MPs this week. "We have had to respond, often at great speed, to find the best way forward, given what we knew about the virus at the time."

Other education ministers around the UK faced similar problems and eventually came up with similar answers, said Mr Williamson.

And Grace got her place back at Oxford. "I just couldn't believe it. It's been a dream of mine for so long. "I wish I could have woken up to an acceptance - but I appreciate it now even more. "It was a flawed system," she said. "And they could have been kinder, especially after everything over the summer."