Youth jail turns to therapy rather than steel doors

- Published

"Secure schools" will aim to stop young offenders becoming adult prisoners. A scene from the youth justice TV drama 'Out of Control'

"Once you're caught in the grip of the system you are doomed," says the founder of a radically different approach to jailing young offenders.

Steve Chalke aims to stop a revolving door of criminality that at present sees 69% of young prisoners reoffending within a year of release.

He says the "19th Century, Dickensian" approach is "absolutely broken".

Instead he will lead England's first "secure school", opening near Rochester, Kent in 2022.

According to the Ministry of Justice's recent White Paper, external, this new template for cutting re-offending must be "schools with security, rather than prisons with education".

'A house, not a prison wing'

The proposed legislation will also allow a charity to run these new institutions - and the charity running the first secure school will be the Oasis group, headed by Mr Chalke.

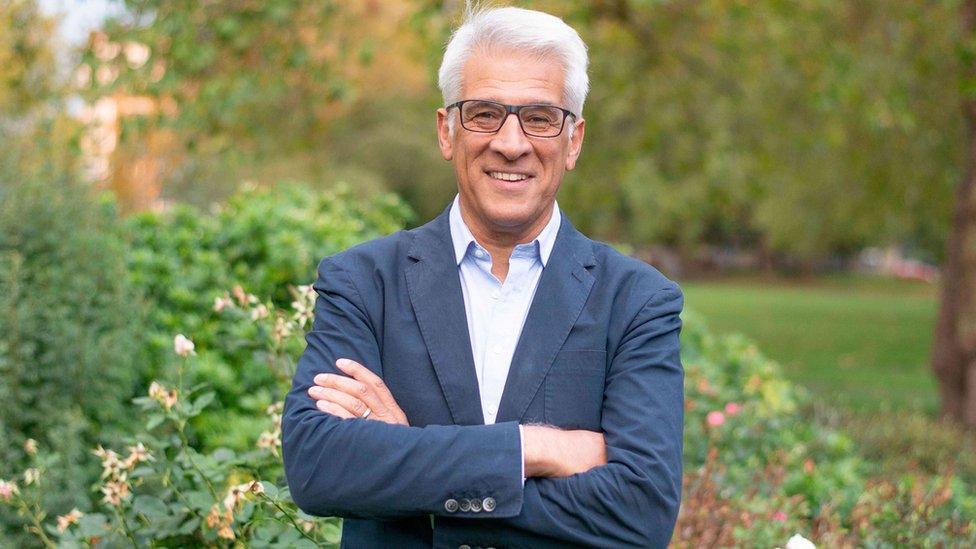

Steve Chalke wants to use idea from neuroscience to address behaviour

"We have to move from a model of justice which is about retaliation to a model that's about resettlement and renewal," he says.

"And the only way of doing that is a psychologically-informed approach."

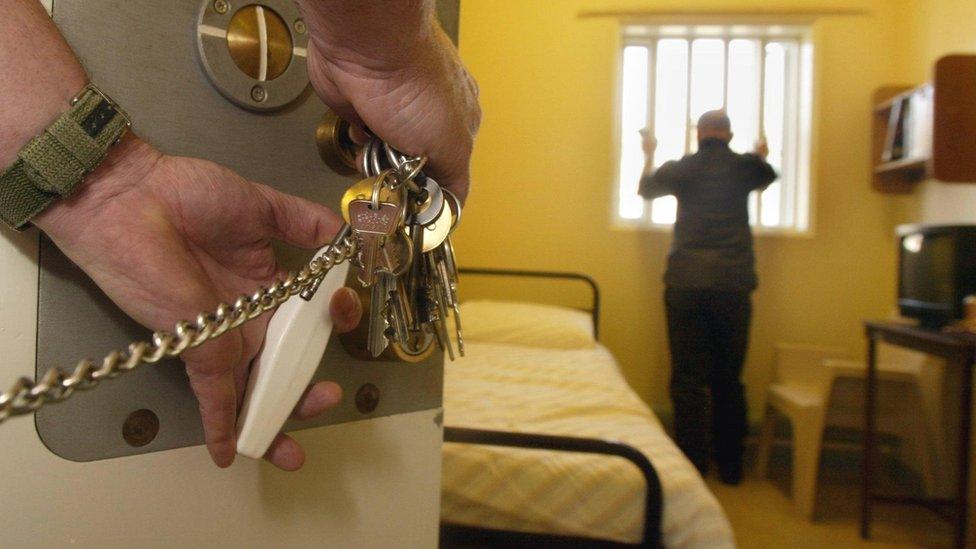

There will be a Scandinavian-style emphasis on therapy and education rather than metal doors and warders with bunches of keys - even though this will remain a secure jail with a perimeter wall.

"There are going to be bedrooms, not cells; a house, not a wing," says Mr Chalke.

He wants to use neuroscience rather than clanging steel doors and bars.

Secure schools want to get away from this kind of image of metal doors and prison wings

Toughened glass, thick wooden doors, electronic fobs rather than locks and keys can be as secure as steel bars, he argues, but with a different and less aggressive atmosphere.

There will be about 50 residents, divided into four houses, and he wants to move away from "retribution" and a system that "scares and intimidates".

Five crimes per reoffender

"So we lock people up in cells and behind bars and all the rest of it, leave them there for three, four or five years, let them go and then wonder why they've not got better," he says.

"When the public talk about the word 'secure', they think of bolts and bars and locks. Whereas, for a lot of young people, what they need is 'security'.

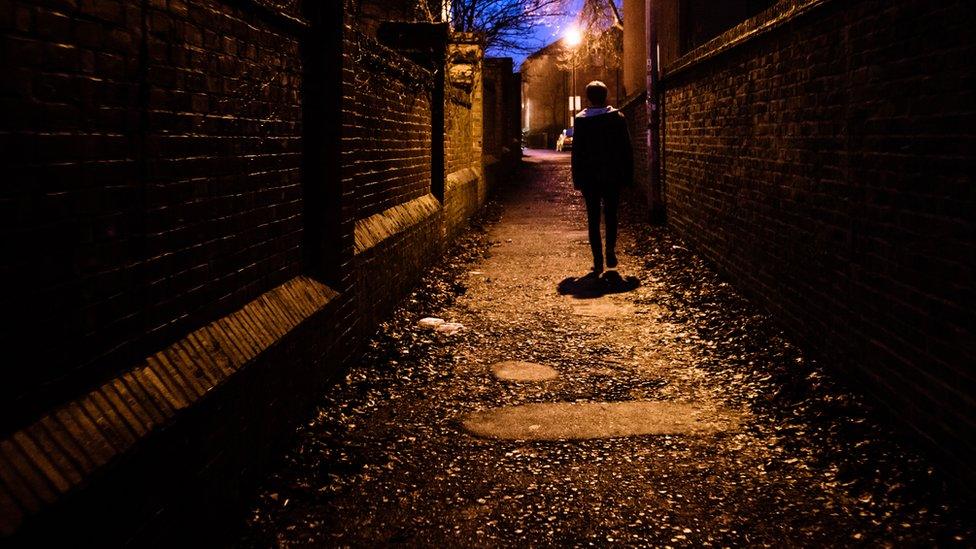

There will be a focus on education and rehabilitation rather than locks and punishment

"I know kids who wish they could go to sleep tonight and feel secure that they won't be woken up by their dad beating up their mum or their mum having another alcoholic row. They want to sleep in security," says Mr Chalke, whose academy trust group runs more than 50 schools.

The starting point has been trying to break the pattern of reoffending - to end the cycle in which offenders enter the prison system as children and then are highly likely to return there as adults.

There's a cost in terms of the victims of crime - for the 69% who reoffend within a year of release, each young reoffender commits an average of five crimes.

Most of those leaving youth custody will go on to be adult offenders

For shorter times in custody, of six months or less, the reoffending rate is even higher at 77%.

And the reoffending rates for those leaving custody are much higher than for young people given cautions or non-custodial sentences.

Assaults

There is also a financial cost. A young offender institution costs £76,000 per inmate per year, a secure training centre place £160,000 and a secure children's home place £210,000 per year.

And House of Commons library figures show there were 269 assaults per month on average in young offender institutions.

The number of young people in custody has fallen sharply in recent years

Mr Chalke wants the secure school to turn the page on how young inmates are treated.

Not least because the challenge is changing.

There has been a rapid reduction in the number of under-18s in custody, down by more than two thirds since 2001, to a current total of about 860. In contrast almost 13,000 were given community sentences.

But Mr Chalke says those in the youth prison system are now a more hard-core group of serious offenders, often with complex psychological problems.

Most young offenders are likely to get community sentences

He wants to use the expertise of mental health services working with dangerous people in secure settings - and to use advances in neuroscience to address the impact of neglect and abuse.

Alongside the education and therapy inside, he wants to set up a much more effective safety net for when inmates are released - helping with accommodation and employment.

In trouble in a day

Mr Chalke tells the story of what he's trying to avoid - a 17 year old released from custody in London, being intercepted by their former gang and sent out as a drugs courier and getting stabbed in a dispute, all within a day.

But the secure school is being built on a troubled site - the former Medway secure training centre.

This was the subject of an undercover investigation by BBC Panorama and was later closed. It's also not far from the village of Borstal, which gave its name to a previous approach at youth justice.

There is a plan for better support for young inmates when they are released

Frances Crook of the Howard League for Penal Reform rejects the positive claims for the secure school - and said it is "not the answer".

She says it is just another in a long list of "reinventing ways of punishing children by locking them up - which always failed".

The prison reform organisation's chief executive said the problem was sending so many children to prison, rather than cosmetic changes to how they were treated.

Youth Justice Minister Lucy Frazer said secure schools would be "vital" in efforts to divert children away from crime.

She said the overall number of offences committed by children has fallen - and that "fewer young people are in custody than ever before".

"However, those who remain are now much more likely to have a complex mix of problems, including persistent absence from school, mental health issues and family problems," said the minister.