Pandemic 'fuelling numbers of children out of school'

- Published

- comments

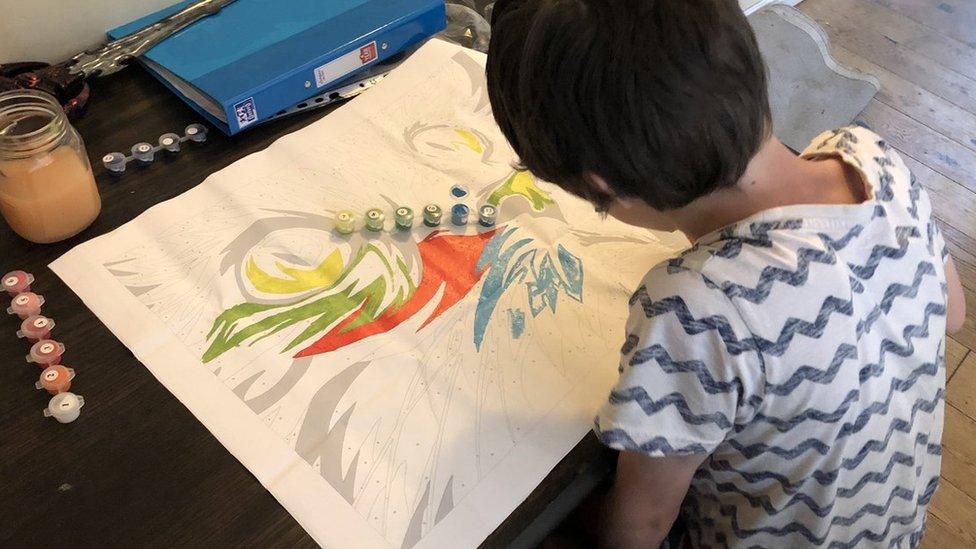

Parents who home educate say it allows them to set a time-table that best suits their child

The coronavirus pandemic could be fuelling an increase in the number of children moving out of full-time schooling, town hall bosses warn.

The Local Government Association says some areas have seen significant rises in registrations for home schooling.

It comes after separate LGA analysis for 2018-19 suggested between 250,000 and a million children in England were out of full-time school.

The government says school is the best place for the majority of children.

A lack of oversight on how and why pupils leave, and where they end up, makes tracking them difficult.

There are no official figures for children who are missing out on school, and the issue has been a challenge for successive education departments which do not track it centrally.

Depending on how "missing school" is defined, the LGA, which represents councils in England. estimates the number could be around 280,000.

But if the point at which councils are formally required to provide tuition for sick pupils - 15 days absence - was adopted as a measure, children out of school would number one million.

The LGA began looking into how many children were out of full-time school before coronavirus hit the UK.

But there are concerns that the pandemic continues to push numbers up, and that the closure of schools and extreme pressure on support systems for special needs and mental health issues, make its findings even more worrying.

The LGA says that between September 2019 and September 2020, some local authorities, saw huge rises in registrations for elective home education.

For example, in Kent the figure rose by almost 200%, and in Leeds by almost 150%.

It is calling for more funds to enable schools to support children and more powers to keep an eye on them if their parents do take them out of school.

Judith Blake, chair of the LGA's children and young people board, says the rising numbers of children not in education are hugely concerning.

"It is hard to tackle due a lack of council powers and resources, and flaws in an education framework ill-suited to an inclusive agenda.

"Children are arriving in schools with a combination of needs, often linked to disruption in their family lives, at a time when schools' capacity to respond is stretched to capacity."

Life-choices

Ms Blake says while parents, councils and schools all have responsibilities to ensure children receive suitable education, significant gaps in the law mean it is possible for children to slip through the net and face serious risks.

These include safeguarding issues, gangs and criminality, serious under-achievement and damaged future prospects.

"The pandemic is only likely to increase these risks and add to the significant lifetime costs to the public purse of a young person not in education, employment or training," she says.

There have always been a small proportion of parents who, for a variety of philosophical, cultural, lifestyle or religious reasons, decide to educate their children themselves, at home.

This is a right, set out in law, which parents are free to exercise.

Philosophical or life-choices remain the most commonly cited reasons but research for the LGA suggests health or emotional reasons are the fastest growing factors.

Some parents make the decision because they are frustrated with "zero tolerance" behaviour policies, their children's refusal to attend or a lack of understanding of their child's particular needs, the report says.

The LGA is keen to stress that not all the children who are taken out of school at the instigation of their parents end up missing out on their entitlement to education, and acknowledges that many parents provide an excellent home education.

It argues, however, that children are more likely to miss out on education if their parents remove them out of desperation because they feel the school is not meeting their child's needs, or out of fear and hostility towards safeguarding or development interventions.

The report concludes: "Many have said that the world after lock-down might never be the same again.

"If that is the case, we should use this period of reflection to determine how we reconnect our education system going forward in a way that we can be confident that all children can access their entitlement to a formal, full-time education."

In a statement, the Department for Education said: "For the vast majority of children, particularly the most vulnerable, school is the best place for their education.

"Home education is never a decision that should be entered into lightly, and now more than ever, it is absolutely vital that any decision to home educate is made with the child's best interests at the forefront of everyone's minds.

"Any parents who are considering home education on the grounds of safety concerns should make every effort to engage with their school and think very carefully about what is best for their children's education.

"The protective measures in place make schools as safe as possible for children and staff, and schools are not the main drivers of infection in the community."