Higher ethnic minority maternity risk examined

- Published

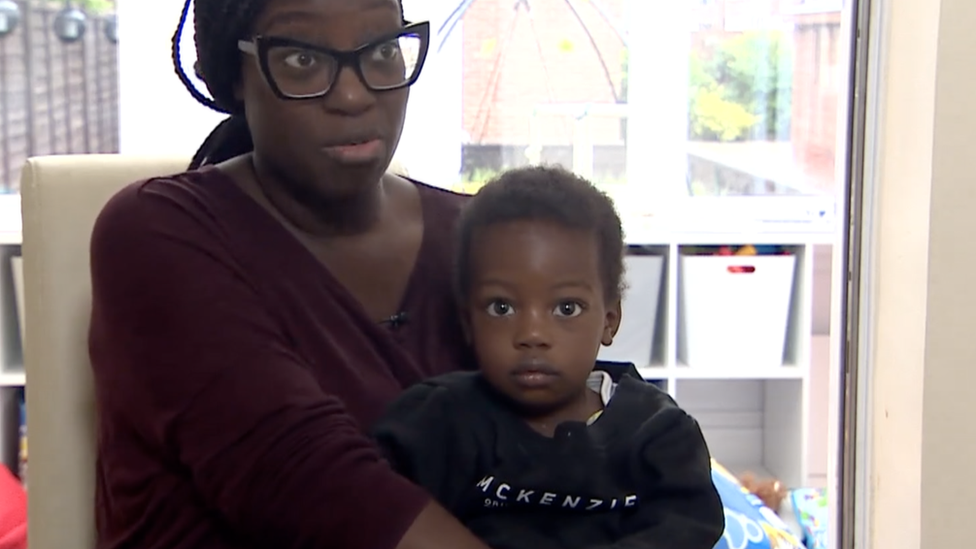

Tricia's son had jaundice as a newborn

A charity has launched an inquiry into why women from ethnic minorities are at a higher risk of serious harm or death in pregnancy and childbirth.

Birthrights says women from ethnic minorities are too often failed by maternity services.

Its year-long inquiry will gather views from parents, midwives, obstetricians and anti-racism campaigners.

NHS England says it is working on a new strategy to tackle inequality in maternity and neonatal care services.

'Really scary'

One of those giving evidence, Tricia Boahene, had concerns her baby might be jaundiced when she left hospital, but felt midwives failed to take her seriously.

"We could definitely tell that he was jaundiced and the healthcare professionals just couldn't see it and that is really scary," she says.

Eventually, her baby had to return to hospital.

"The healthcare professionals really struggled to recognise the jaundice, because my son is darker skinned," Tricia says.

"I do feel perhaps if he was lighter, even lighter but still black, they may have noticed it a lot sooner.

"It definitely felt that they just couldn't see my son, possibly in the way they would their own child, and definitely his skin colour had something to play in that.

"I don't think it is necessarily unusual for healthcare professionals to do all that they can to put the mother at ease - you know, 'Don't worry, it's probably not that big a thing of a deal,' - but it definitely felt that I was not being heard until I really, really had to push."

'Don't understand'

Sabia Kamali says she could have avoided an emergency Caesarean section if her pain had been taken more seriously.

"When I said that I needed extra painkillers because gas and air wasn't enough, they were like, 'Oh no, it's normal, we'll come back, it's nothing, women go through that all the time.'

"So it's like shunning the idea that you are in pain."

Often not "very forceful", Asian women can be overlooked by professionals, Sabia says.

"What they tend to do is that they categorise you in say the ethnic box, or the Bangladeshi, the Muslim," she says.

"They think because you look a certain way, you dress a certain way, they think you don't understand things."

Sabia says everyone should be seen as an individual

While death in pregnancy or childbirth is rare, black women are four times more likely to die during or up to the first six weeks after pregnancy than white women, according to the UK Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths, published in 2019, which blamed racial discrimination, stereotypes and cultural barriers.

And, according to the Office for National Statistics, about a quarter of women giving birth in England and Wales belong to ethnic minorities.

Research suggests they have poorer pregnancy outcomes than white women and poorer experience of maternity care, the ONS says.

They tended to access antenatal care later in pregnancy, have fewer antenatal checks and ultrasound scans, less screening and were less likely to receive pain relief in labour.

Black African women in particular were more likely to deliver by emergency Caesarean section.

'Survive childbirth'

NHS England chief midwifery officer Jacqueline Dunkley-Bent said: "The NHS is one of the safest healthcare systems in the world to have a baby and all women who use our maternity services should receive the best care possible - which is why we acted immediately to boost support for pregnant women from ethnic minority backgrounds, when heightened risks first became clear.

"We are working on a new strategy to tackle inequality in maternity and neonatal care and have been fast-tracking our continuity of carer programme for women from ethnic-minority backgrounds, which is proven to significantly improve their overall experience of care."

Birthrights chief executive Amy Gibbs said: "UK law demands everyone has equal access to safe, respectful maternity care but we are failing to safeguard black and brown people's basic rights - to survive childbirth, to be treated with dignity, to have their bodies and choices respected."

Shaheen Rahman QC, who will chair the inquiry, said: "We want to understand the stories behind the statistics, to examine how people can be discriminated against due to their race and to identify ways that this inequity can be redressed."

The early findings from the Birthrights investigation - supported by law firm Leigh Day - are expected to be published in the autumn, ahead of the full report in February 2022.