GCSEs 2021: The big divides becoming even wider

- Published

When the storm of the pandemic finally subsides, what long-term damage will it leave behind?

After this week's GCSE and A-level results, there is a warning the legacy for education will be an even wider social divide.

Those ahead before the pandemic are even further ahead now - and those losing out before have slipped further behind.

Years of clawing back the "attainment gap" have rapidly unravelled.

The exam results revealed a "long-term, deep-rooted widening of inequality", the Social Mobility Commission said.

'Crowd out'

"At the same time as the gap widening, there has been an increase in the top grades, which has happened disproportionately in the most privileged schools," social-mobility commissioner for schools Sammy Wright said.

And, Mr Wright, vice-principal of a school in Sunderland, suggested, this boom in top grades for the most advantaged could "crowd out" other people from opportunities such as university places.

The GCSE results in England show a full line-up of widening gaps.

The biggest increase in top grades has been in independent schools, with 61% achieving grade 7 or above, compared with 26% in comprehensives.

Girls have taken an even bigger share of top GCSE grades this year

It is a figure future generations might puzzle over - even in a year without exams, pupils at fee-paying schools were still emerging with hugely better results.

Girls, already more likely to achieve better results than boys, stretched even further ahead.

While 33% of girls' results were top grades, it was 24% for boys, a really significant gap.

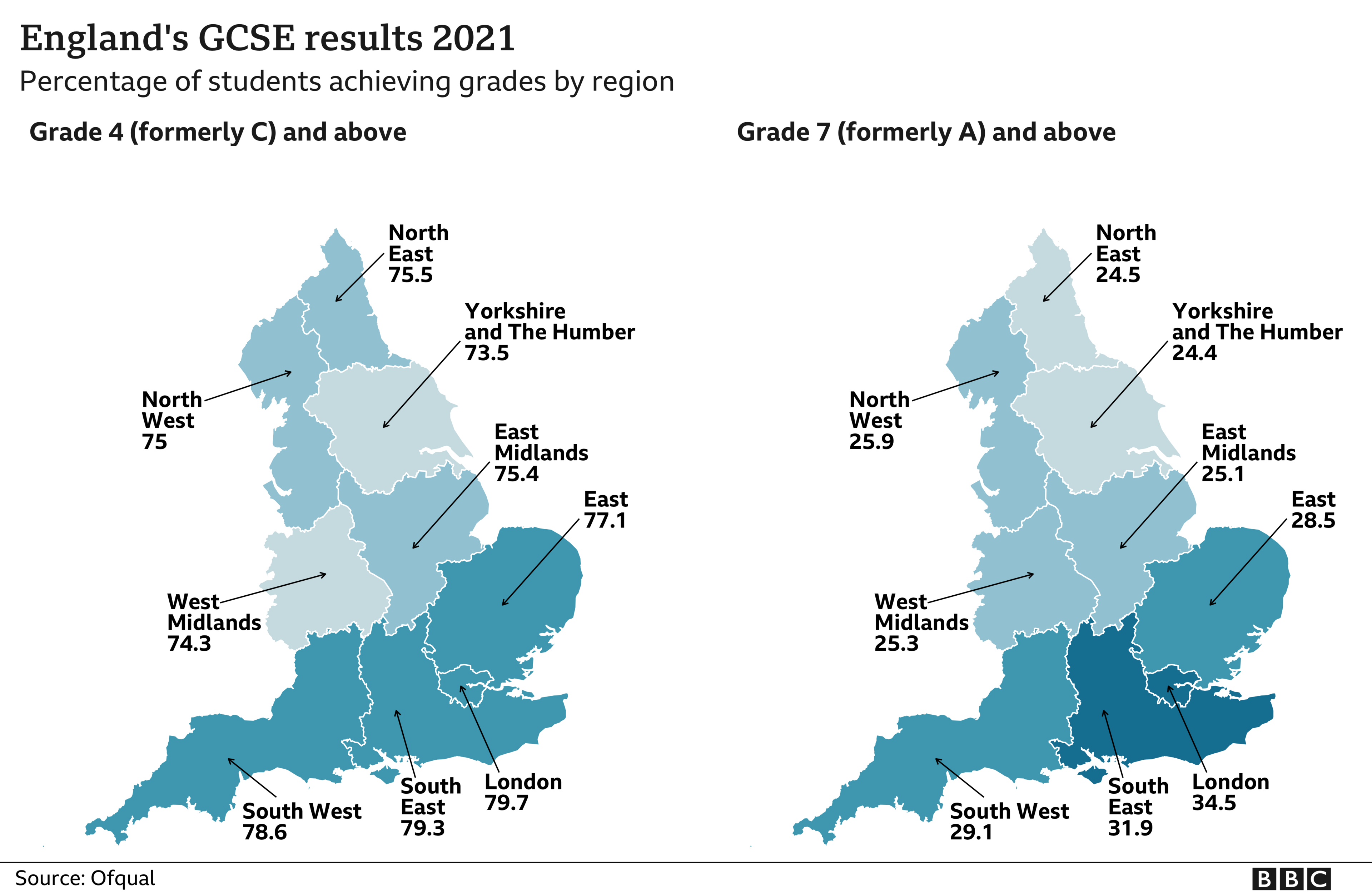

And the regional divide has grown, with London even more ahead of parts of the north of England.

The GCSE results map shows a broad north-south divide.

Pupils on free school meals also fell further behind in the GCSE results.

Notch higher

The pandemic has had an amplifying effect - those with advantages have increased them.

Like Spinal Tap, it has pushed all the levels up a notch higher.

And this divide is not a temporary blip that will fade away, according to former education recovery commissioner for England, the "catch-up tsar", Sir Kevan Collins.

The decision about how to support a recovery will be the defining moment for the next decade of England's education system, he said.

It is worth remembering how much disruption has been faced by this year's GCSE students.

Of five years in secondary school, two have been turned upside down by the pandemic.

Next year's exams are already having to be adapted.

And the difficulties will not have been evenly spread.

Like everything else in the pandemic, there were very divided experiences.

Home-schooling was profoundly different depending on:

access to technology

parental support

space to work

There have been warnings too of tens of thousands of young people effectively slipping out of the school system.

Big challenge

It will also be politically hard to close the gap, if that includes pulling back some of those who have raced ahead.

For A-levels, the increase in top grades in independent schools has been remarkable in the pandemic - up from 46% to 70% in two years.

Increases in exam grades soon become what is expected and it becomes very difficult to let them fall again.

The pupils getting their GCSEs and A-levels this week have plenty of reasons to be proud, emerging with record grades after both of their exam years were overshadowed by the pandemic.

But it will be a big challenge, for years ahead, to make sure a fair chance in school does not become an unforeseen casualty of the pandemic.

TEST AND TRACE: How does it work?

QUARANTINE: Will I need to self-isolate in a hotel?

COVID IN SCHOOL: What are the risks?

NEW VARIANTS: How worried should we be?