Overcrowded specialist schools: ‘We’re teaching in cupboards’

- Published

Head teacher Rob Mulvey says he's ashamed that some children are being taught in a cupboard

Half of state-funded schools in England for children with special educational needs and disabilities are oversubscribed, BBC research has found.

Schools have converted portable cabins and even cupboards into teaching spaces because of a lack of room. Head teachers say this puts pressure on staff and makes pupils anxious.

Parents say the wait for places means their children are missing education.

The Department for Education says it is spending £2.6bn on new places.

Sarah is in her son Cohen's classroom - not to pick him up, but to collect his things a year after he stopped coming to school.

Maltby Hilltop School in Rotherham is a specialist school for pupils aged two to 19 with severe learning difficulties and complex needs. Because of a lack of space and overcrowding in the main building, Cohen's classroom is in a portable cabin, with loud floors and thin walls.

The 14-year-old is autistic and has a condition known as pathological demand avoidance (PDA), which leads to a rigid need for control when he's anxious.

Cohen struggles to manage his condition if he's not in a calm environment - and Sarah,. whose full name we are not using, says the school simply did not have enough physical space to provide that.

"He started to have panic attacks and hyperventilating," she says.

"He wants to be here, but the space isn't allowing it."

Sarah worries that her son Cohen is missing out on life-learning skills, now that he's no longer at school

Sarah is trying to get Cohen into a different specialist school but says there are no places available until September.

The shortage of places in special educational needs schools is a problem across the UK, with unprecedented demand for support.

Advances in life expectancy, more awareness and better diagnosis means there are now more children and young people with needs that are difficult to meet within mainstream schools. The pandemic has added to a system already under pressure.

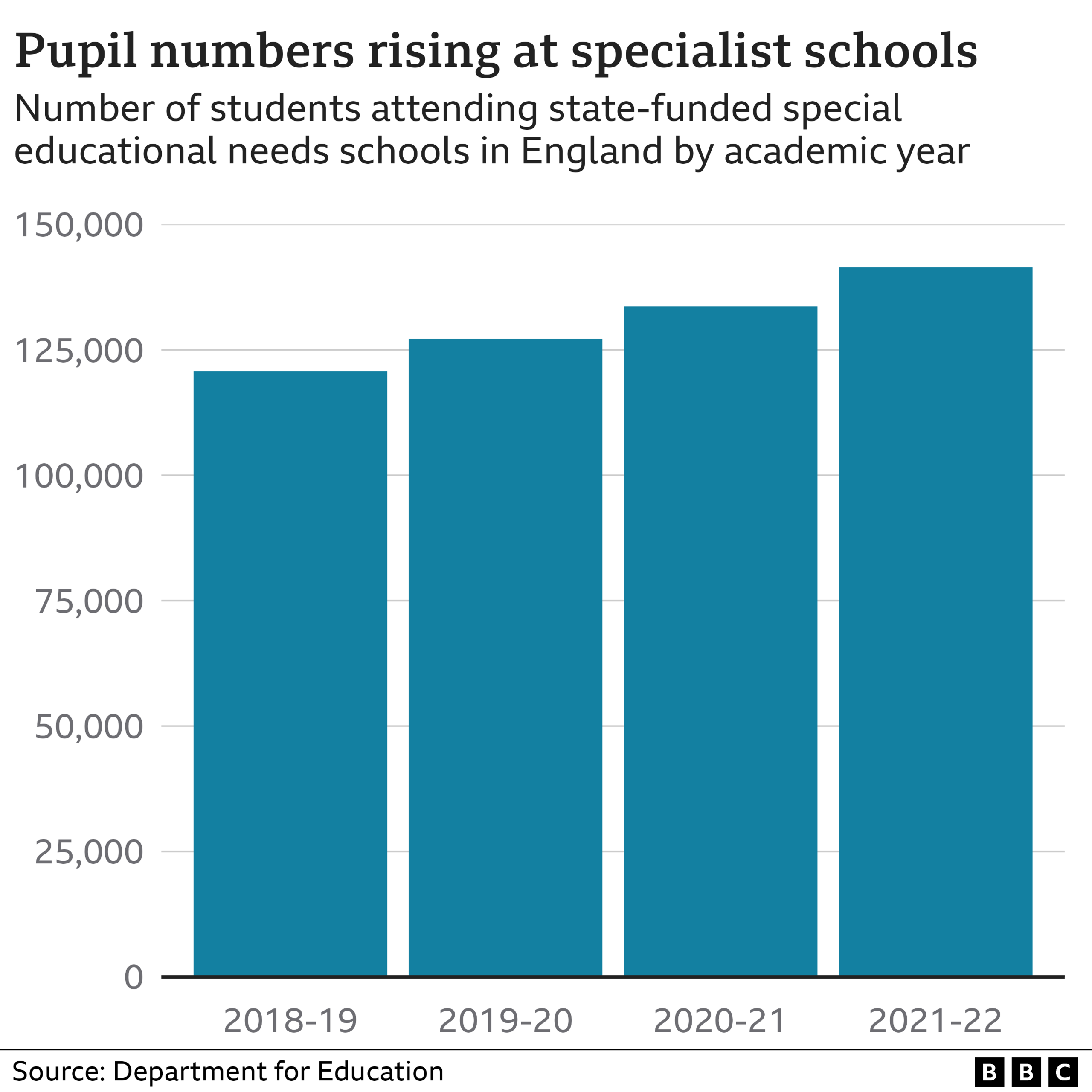

Over the past five years, the number of children and young people being educated in specialist schools and colleges in England has increased by nearly a third - to 142,028 last year.

Special educational needs schools across the UK are under pressure because of a shortage of places. Families invite the BBC's Elaine Dunkley to see the challenges they face as they fight for a school place.

Available now on BBC iPlayer (UK only)

Cohen is one of three pupils who are no longer able to attend classes at Maltby Hilltop because they are struggling to cope with the overcrowding and noise.

He is currently at home and spends most of his time alone in his bedroom. Sarah says he's "not engaging in anything" and is "missing out on learning life skills" as he waits for a suitable school place.

As she flicks through the colourful drawings, workbooks, and pens in her son's school drawer, she adds: "He should be learning, and he should be with his friends."

BBC News compared pupil headcount data to the number of commissioned places at 1,012 state-funded schools for children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) in England during the 2021-22 academic year.

We found that just over half (52%) of SEND schools had more children in classes than their number of commissioned places.

Storage space for wheelchairs and pupils' equipment is in short supply at Maltby Hilltop

When head teacher Rob Mulvey joined Maltby Hilltop in 2011, 82 children were enrolled. That had risen to 99 pupils by 2019. This year there are 134.

Wheelchairs, walking aids and medical equipment line the corridors. There is no longer a dinner hall - children eat in their classrooms, because the space is being used instead for large trampolines to provide therapeutic exercises for children with a variety of disabilities and additional needs.

A cupboard which used to store stationery is now used for lessons and as a therapy room for visually-impaired pupils. It can only fit two pupils in at a time, and there are no windows or natural light.

Mr Mulvey says the fact that children are having to learn in a cupboard rather than a proper classroom is "absolutely tragic" and "morally wrong".

"As the head teacher of the school, I genuinely do feel it is shameful that this is what we are providing for our children. They deserve so much better."

Local authorities commission school places in consultation with specialist schools to assess how many children can attend, but councils can and do ask schools to take on even more pupils.

A school must take on a pupil if that school is specifically named on their Education, Health and Care Plan (EHCP), which is a legal document outlining the support a child needs. While councils can refuse requests, this is often challenged by parents who normally win in costly tribunals.

Nationwide, the number of pupils with EHCPs has risen by 50% since 2016, to just over 355,500 last year.

Maltby Hilltop was built in the 1970s, and its concrete slab, modular structure makes it difficult to build upwards. Its position on the side of a hill also makes building work prohibitively expensive. Mr Mulvey says the school is at capacity.

"We have thought about every inch of the school and what we can do to make it better, and there's no more that we can do," he says.

"The demand for places is growing evermore. There are some desperate families out there who really do need a place at this school, but we cannot offer it."

Money for specialist schools comes from the high needs funding given to councils. Per pupil funding at specialist schools starts at £10,000 per child and is topped up further depending on need.

If a school takes on more pupils above their commissioned places, it won't necessarily receive the full high-needs funding for each additional child - that's a decision for the local authority.

Despite an extra £400m in high-needs funding announced in the Autumn Statement, the Local Government Association (LGA) says councils are facing "significant financial challenges" and need long-term certainty over funding to support children with SEND.

Louise Gittins, a councillor and chairwoman of the LGA's children and young people board, has told the BBC that if no action is taken, councils will be in deficit by £3.6bn on SEND spending by 2025.

She also called for the government to urgently publish its long-awaited proposals "for a reformed system which better meets the needs of children with SEND".

Head teacher Rob Mulvey is calling for a long-term solution, not "sticking plasters"

In response to the BBC's findings, the Department for Education said it was providing £2.6bn in capital funding up to 2025 to help deliver new places at SEND schools. It added that it had increased high needs funding by 50% since 2019, to over £10bn by next year.

Head teacher Mr Mulvey says specialist schools need more investment from both the government and local authorities.

"We don't need sticking plasters. We need a long-term solution to increasing the places and availability for children with additional needs."

Additional data research by Wesley Stephenson.

Are you affected by issues covered in this story? Share your experiences by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at HaveYourSay@bbc.co.uk, external. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.

Related topics

- Published13 December 2022

- Published29 March 2022

- Published2 December 2022

- Published8 September 2021