School concrete crisis: Your questions answered

- Published

More than 100 schools in England have been ordered to partially or fully shut buildings over concerns the concrete they were constructed with is unsafe.

We put your questions to Professor Chris Goodier, concrete expert at Loughborough University, the BBC's education correspondent Hazel Shearing and BBC digital lead for education news Alice Evans to find out what this means for you.

Why were schools built like this?

There is nothing fundamentally wrong with reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC) as building material or system. Many buildings from the 60s and 70s built from many materials are now having problems due to inadequate maintenance, and old age. Many RAAC buildings are 50-plus years old and are doing fine.

No material has a perfect lifespan. Even if they have been built the same, the health of the buildings will be in different conditions - some will be fine and some will be suffering.

Will more schools have to close?

More closures or partial closures are likely.

The Department for Education (DfE) has not given specific numbers of schools that need to close as a result of Thursday's announcement.

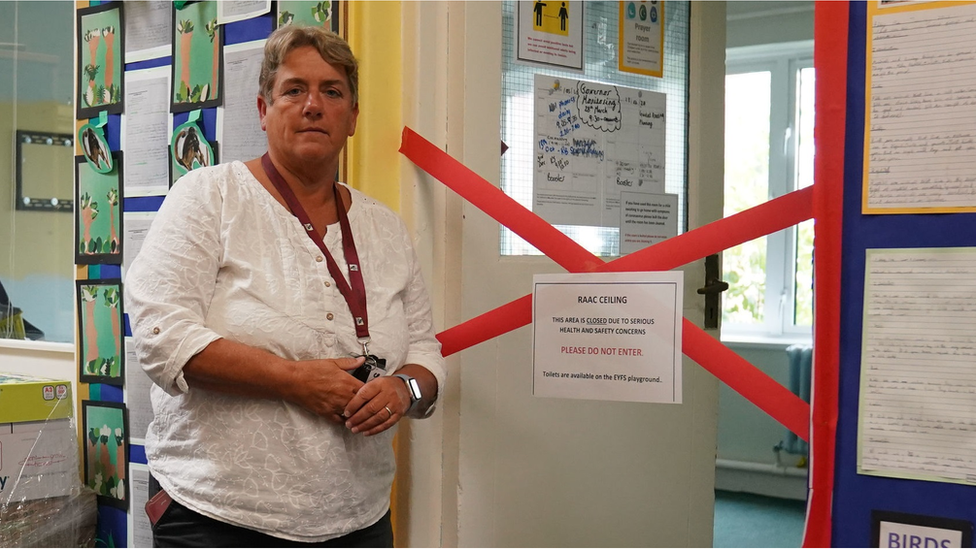

Schools with RAAC only have to close or partially close if they do not have safety measures in place, and cannot make alternative arrangements - such as converting other parts of the building into temporary classrooms or moving children to another site.

A total of 156 schools have confirmed RAAC. Of those, 52 have already put safety measures in place. The other 104 are currently scrambling to put safety measures in place to stay open - as many as 24 of them may have to fully close.

But hundreds more schools are yet to conclude whether or not they have RAAC. Back in June, a report by the National Audit Office assessed that 572 schools had been identified where RAAC might be present.

The government has not said when a list of affected schools will be published

How will I know if my child's school is closed?

If your school is closed, it should get in touch with you directly.

Education Secretary Gillian Keegan said on Thursday that affected schools would be contacting parents directly, adding: "If you don't hear, don't worry."

The affected schools will be trying their best not to close completely. Some pupils have already been told they will be learning remotely, in temporary classrooms or at different schools.

Since the government has yet to publish the list of schools affected, BBC News has been doing its own digging. Schools affected that we do know about are listed here.

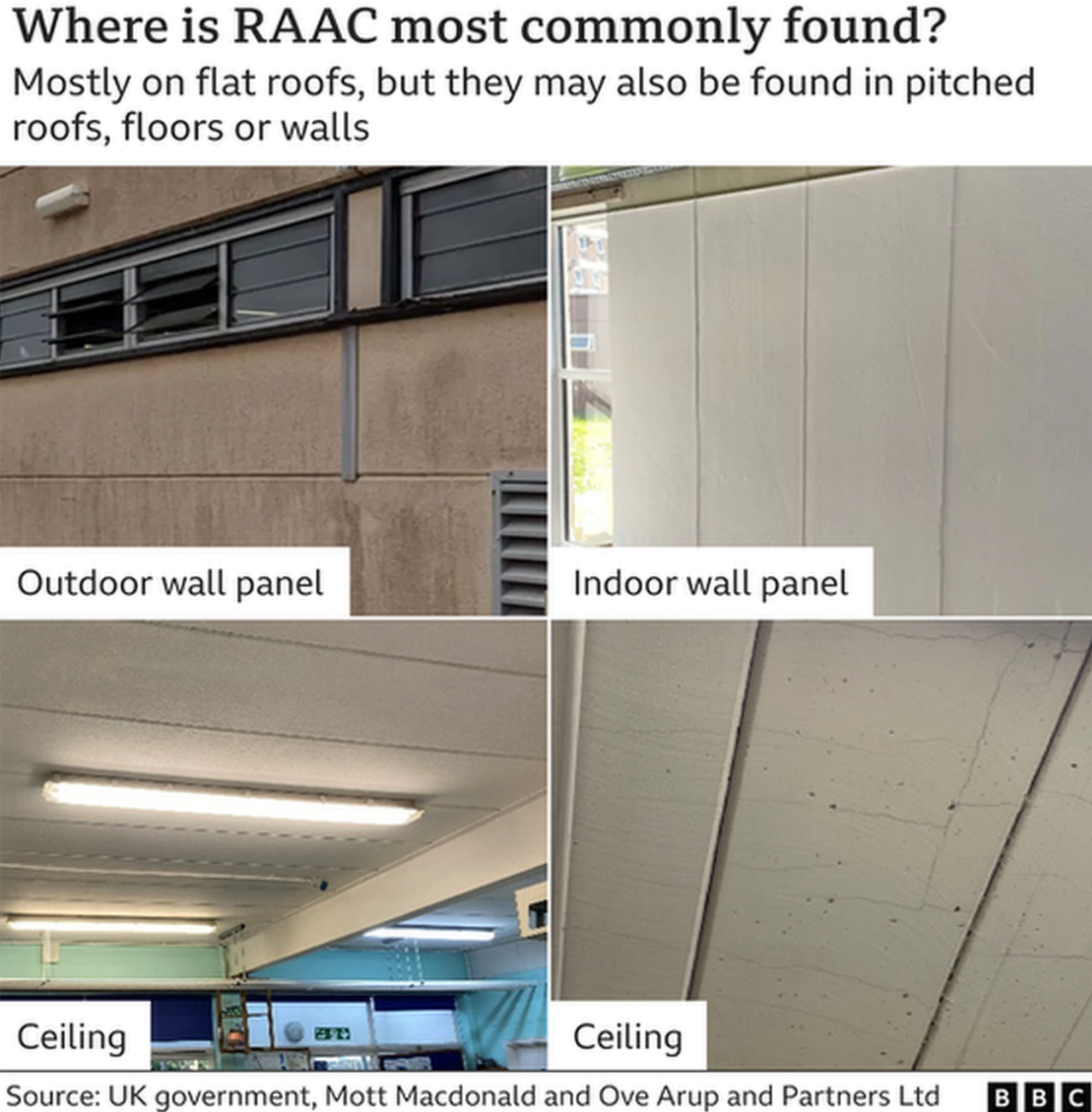

Is this only a problem in schools?

No. Numerous public buildings have been identified as being at risk because of RAAC, including hospitals and police stations.

Why is the government being blamed?

The government says it has advised schools to have "adequate contingencies" in place since 2018, in case affected buildings needed to be evacuated.

But one of the reasons it is being criticised is because it did not get an idea of the scale of the problem back then.

It is hard for schools to identify whether or not their buildings contain RAAC because it looks like normal concrete.

Many may not have known they had it in 2018 as engineers are needed to confirm it.

It was not until 2022 - four years later - that the DfE sent a questionnaire to schools asking if they had any confirmed or suspected cases of RAAC. If the school said yes, the DfE sent out engineers to confirm it.

Another issue here is the last-minute change of guidance days before the start of the new term.

Previously, schools with confirmed RAAC that was thought to be a non-critical risk had been told to have contingency measures in place just in case buildings needed to close.

It was only on Thursday they were told to shut those buildings unless safety measures were in place, meaning head teachers are now having to scramble to find alternative plans.

Why was this not sorted during the Covid pandemic?

Ministers would probably say the reason building work has not happened earlier is that they did not know about the problem in these particular schools until very recently.

The government does say it has advised schools to have "adequate contingencies" in place since 2018, in case affected buildings needed to be evacuated.

But it was only over this summer that a few different incidents - including a beam collapsing in one building - led the government to decide that some RAAC they had previously considered to be low risk was actually dangerous.

That was why they have now issued the more serious warning that affected schools should put in safety measures or close off the affected part of their building.

Why is the guidance different in Scotland?

The change of guidance applies to England only at this stage. We don't yet have a full picture of the situation in the rest of the UK.

Scotland has already started to inspect RAAC in its school buildings, and a full report on how many schools in Scotland are affected is due to be delivered to the government soon.

According to the Liberal Democrats, RAAC was found in at least 37 schools in Scotland.

The Welsh government has said it will survey the country's schools and colleges to check if any are made with RAAC. In Northern Ireland, surveys are under way.

The reason it's different depending on where you live is because education is run by devolved governments in each nation.

Questions were asked by readers including Christopher Grierson, Frederick Bate, Amanda Elvines and Ray Chester.

- Published2 September 2023

- Published13 February 2024

- Published31 August 2023

- Published1 September 2023

- Published19 September 2023