Raac in schools: MPs demand answers over dangerous concrete

- Published

Some schools with Raac have had to close off small areas, but others have had to shut entire buildings

A "lack of basic information" about work to address dangerous concrete in schools in England is "shocking and disappointing", a report by MPs says.

The Department for Education (DfE) should say how many surveys are yet to be carried out and how many temporary classrooms have been ordered, it said.

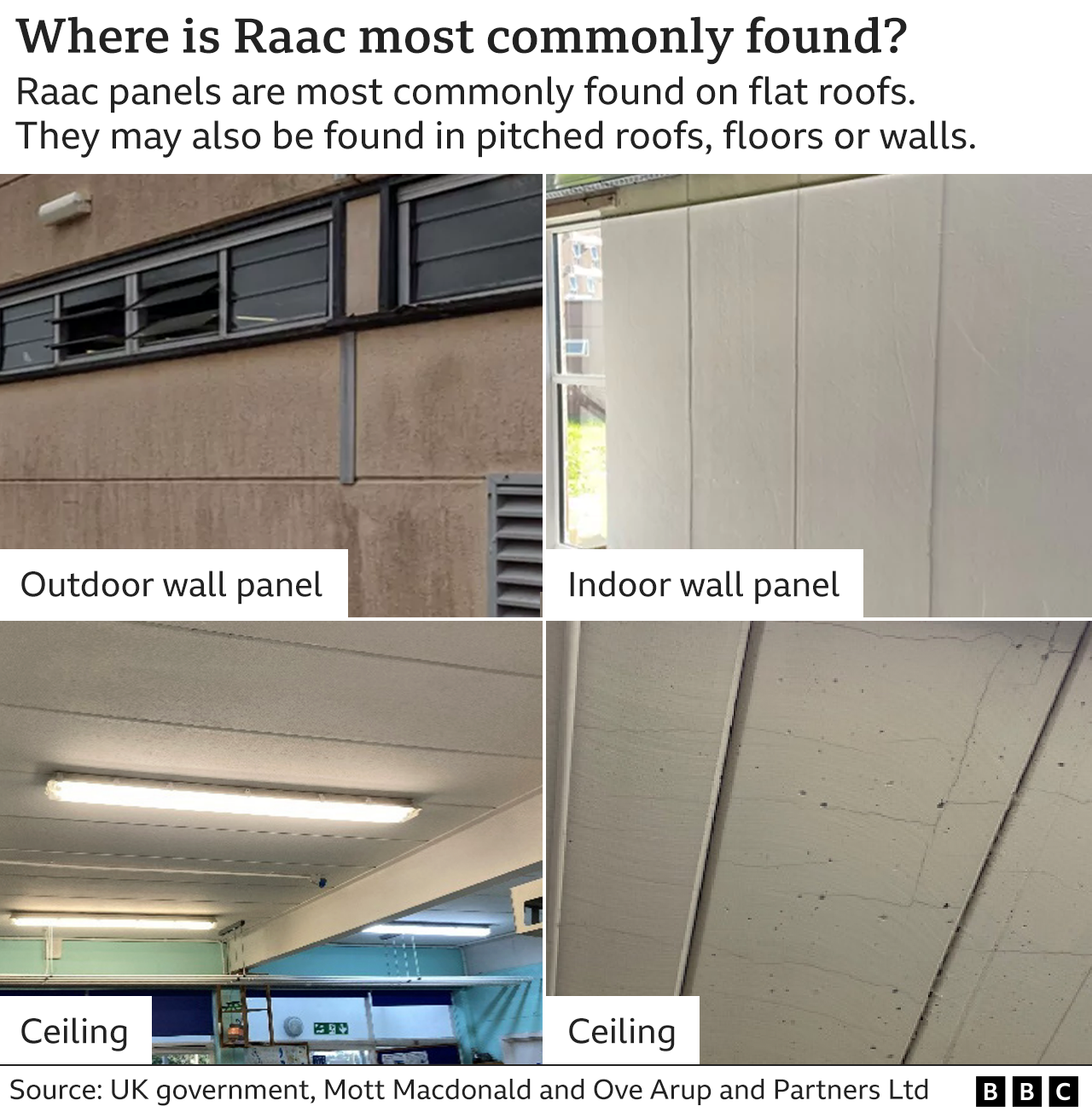

The report comes a month after the last official list confirmed 214 schools and colleges had reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (Raac).

The DfE rejected the assessment.

A spokeswoman said the government had "taken swift action, responding to new evidence, to identify and support all schools with Raac to ensure the safety of pupils and teachers".

Labour's shadow education secretary Bridget Phillipson said Education Secretary Gillian Keegan "should come to the House of Commons and explain when she and her Conservative ministers are going to get a grip of this crisis".

The Public Accounts Committee, which scrutinises the delivery of public services, warned the list of schools with Raac would grow, and expressed concern that the DfE "does not have a good enough understanding of the risks in schools".

Its report set out 10 recommendations for the DfE, calling on it to:

confirm the scale of the Raac problem, including how many pupils have been affected by school closures

"urgently assess" whether questionnaires returned by schools and specialist surveys could be inaccurate

set out its plans to remove all Raac from schools

Dame Meg Hillier, chair of the committee, said many schools were "still not sure where they stand or whether they'll get the money to sort out the problems that they've got".

The report also stressed broader concerns about the state of school buildings, noting that the DfE was yet to establish whether asbestos was present in around 1,000 schools.

It warned that the government's School Rebuilding Programme was behind schedule and would not be able to help many schools that ultimately need rebuilding.

The condition of schools was worse in the north of England, it added, as well as in rural and coastal areas.

A DfE spokeswoman said questionnaire responses had been gathered from all education settings "in affected areas" and most schools did not have Raac.

"We have been clear that we will do whatever it takes to remove Raac from the school and college estate. We are working closely with schools with Raac to ensure remediation work is carried out and disruption to learning is minimised," she said.

"Our School Rebuilding Programme is continuing to rebuild and refurbish school buildings in the poorest condition, with the first 400 projects selected ahead of schedule."

An estimated 700,000 children in England are being taught in unsafe or ageing school buildings that need major repairs, according to a National Audit Office report from June.

The presence of Raac was thrust into the spotlight at the end of August when the government told affected schools without safety mitigations to shut days before the start of term.

The sudden change in approach left some pupils learning from home for weeks as head teachers scrambled to make alternative arrangements. The DfE spokeswoman said "only a small handful" of schools taught remotely "for a short period".

The DfE first published a list of affected schools on 19 September. It had suggested it would update it every fortnight, but so far that has only happened once, on 19 October.

It said 202 of the 214 were now offering full-time face-to-face education.

For some schools, that may mean things are more or less back to normal.

But at others, children are being taught in sports halls, corridors, temporary classrooms including marquees, nearby schools and external buildings.

One parent, whose children's school was waiting for asbestos to be cleared so a Raac survey could be carried out last month, told the BBC she felt her children had been forgotten.

In September, the DfE suggested 29 schools required temporary classrooms, of which 11 already had them in place, and orders have been made for at least 180 single and 68 double classrooms.

This month, the government awarded three contracts worth up to £35m to providers of temporary classrooms.

Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, said it "appears to be taking an eternity to put in place remedial measures".

"We are gravely concerned that when the government eventually gets around to permanent solutions for affected schools it will do so at the expense of other schools that desperately need upgrading," he said.

Paul Whiteman, general secretary of the head teachers' union NAHT, said he was "increasingly concerned", especially for exam students in affected schools.

"Many schools are still awaiting temporary classrooms and are having to repurpose dining halls, PE facilities, and spaces for after-school provision and wrap-around care," he said.

Daniel Kebede, general secretary of the National Education Union, said schools needed "substantial new money to tackle a crisis in school buildings".

A Save Our School sign put up during a parents' demonstration over Raac outside St Leonard's Catholic School in Durham

Are you affected by the issues raised in this story? Share your experiences by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at HaveYourSay@bbc.co.uk, external. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.

Related topics

- Published13 February 2024

- Published11 October 2023

- Published19 September 2023

- Published1 September 2023

- Published28 June 2023