The general election candidates with no hope of winning

- Published

Joe Goldberg (third from right) took on David Cameron for Labour

The next general election might be hard to predict, but many candidates in so-called safe seats can already be confident they will lose. What drives people to spend months knocking on doors, only to get roundly thrashed on polling day?

Well over half of the 650 seats up for grabs are "very unlikely to change hands" on 7 May, according to the Electoral Reform Society.

That won't stop candidates from rival parties - not to mention independents - from putting themselves forward.

"No-one in their right mind would stand in a safe seat unless they saw it as a stepping stone," says Steven Fielding, a professor of political history at Nottingham University.

While there could be upsets in an "extraordinary" election, running against the favourite is usually a thankless task with little support from party HQ, he believes.

Tony Blair, centre, as a by-election hopeful in 1982

"You get nothing, absolutely nothing, it will be a very lonely experience. Your party will be very small, many activists will be drafted into marginal seats, it must be a very dispiriting experience."

Prof Fielding said the use of safe seats as a "stepping stone" for future high-flyers seemed to be diminishing, as more favoured candidates are propelled into close-fought marginals or safe seats of their own.

But it has been the first step on the Westminster ladder for many leading figures in British politics.

They include Boris Johnson, who ran in the safe Labour seat of Clwyd South ("I fought Clwyd South - and Clwyd South fought back", he said) and Tony Blair, who came a distant third in a by-election in Tory stronghold Beaconsfield South in 1982.

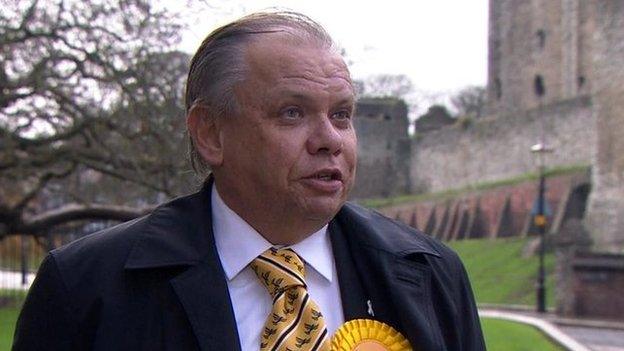

Lib Dem Geoff Juby got 349 votes at the Rochester and Strood by-election

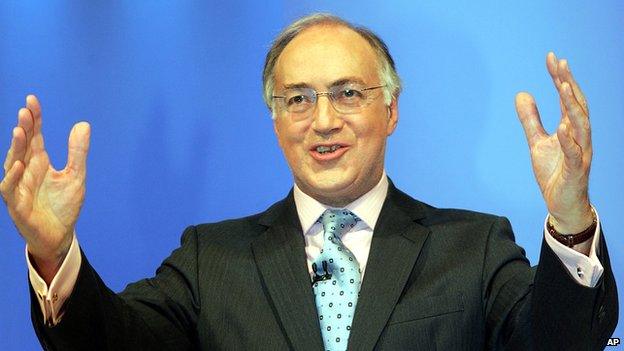

Former Home Secretary and Conservative Party leader Michael Howard has fond memories of his first two attempts to get elected, in Liverpool Edge Hill in 1966 and 1970.

"I enjoyed them both tremendously," he says.

"In some respects, particularly in the first election, it was a bit lonely.

"I remember canvassing on my own in the snow - it was quite a cold winter - but apart from other occasions like that, I had a small but very loyal band of followers, we worked together and had a lot of fun.

"The electorate was not at all hostile, obviously it was a Labour seat but very friendly and very funny.

Michael Howard's journey to the Cabinet began with defeat in the Labour stronghold of Liverpool Edge Hill

"A lot of people said they would never vote for me in a month of Sundays, but they said it with great humour."

In November's Rochester and Strood by-election, Liberal Democrat candidate Geoff Juby managed 349 votes - the worst ever performance in a by-election by a governing party.

"I quite enjoyed it," insists Mr Juby.

"If you want to do politics it's a good experience in a constituency you are not going to win... you get used to the media and the public meetings, it's a good grounding, that's why people do it.

"I would recommend everybody do it in their life, it's a good experience."

Was he not dispirited? "I think if I had been 20 years old I might have been, but when you get to a certain age, life goes on."

If you're going to try and claim a scalp in a safe seat, they don't come much bigger than the leader of your rival party.

Joe Goldberg tried to unseat local MP David Cameron for Labour in Witney in 2010, finishing third as the future prime minister coasted to a 22,740 majority.

Strongest strongholds

After the 2010 general election, the safest seat in percentage terms was Liverpool Walton, where Labour MP Steve Rotheram has a 57.7% majority

The largest majority in terms of votes is 27,826, held by Labour's Stephen Timms in East Ham

The safest Conservative seat by both measures was Richmond in Yorkshire, where William Hague's majority was 43.7% or 23,336 votes

"You're not going to beat David Cameron when you're standing in Witney, it's not going to happen," the 38-year-old says, insisting that despite the "huge commitment" his campaign required, he does not regret it "for a minute".

Taking part in a Hustings debate against the Tory leader was "something to tell the grandchildren", he says.

But his reason for standing is probably shared by also-rans across the country.

"It's about making sure that there's a voice for people who have a slightly different point of view," he adds.

"That's part of the democratic process."