Voters targeted on digital front line

- Published

With voters increasingly looking online for their news, updates and commentary, could the digital world offer political parties a crucial, decisive edge in May's election?

Many politicians seem to think so, spending ever more time and resources campaigning on social media.

The power of Barack Obama's victories in the 2008 and 2012 US presidential elections proved the power of digital campaigning. He amassed 23 million Twitter followers and 45 million Facebook likes, using this massive digital following to organise more than 300,000 offline events and raise $690 million.

Since then, politicians around the world have tried to follow suit. During the 2014 Indian election Narendra Modi enlisted 2.2 million volunteers using online tools, engaging with hundreds of thousands of people to crowd-source his Bharatiya Janata Party's manifesto, as he swept to power.

Now British parties have been importing highly prized experts in digital campaigning. The Conservatives are reportedly spending £100,000 a month on personalised advertising via Facebook, while Labour has been organising an army of volunteers to not only fight the "ground war" on the streets but also to pound the digital pavements at #labourdoorstep.

Politicians are making increasing use of digital platforms, with around 80% of MPs elected to the last parliament using Twitter - most every day - and about half using Facebook once a week. More than 1,000 of this year's parliamentary hopefuls are sending a deluge of digital campaigning in the direction of the electorate: around 20,000 Tweets a week.

BBC Asian Network and Demos are teaming up to look at the digital campaign from the point of view of the voters. Throughout the campaign, we'll follow the social media experiences of three people firmly in the crosshairs of the parties' online armoury: young, enthusiastic users of social media and, most importantly, undecided.

Iram Asim, 31

Iram is voting in the West Lothian constituency of Livingston. Labour held the seat with a massive majority in 2010 but, with polls suggesting the SNP could make dozens of gains, the seat is now on the front line of the contest between the parties. Iram, a full-time mother, is wavering between Labour and the SNP because of the volume of information available.

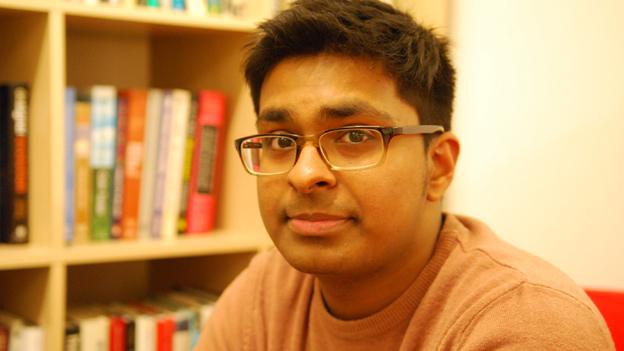

Sakib Rashid, 20

Sakib is a first-time voter in north London's Brent North constituency, where Labour is trying to see off a Conservative challenge. Both parties have policies he likes and dislikes, and he's struggling to pick. It's one of only two seats in England and Wales where more than 50% of eligible voters are predicted to be foreign born. Sakib, a student originally from Bangladesh, is among them.

Simmi Juss, 32

Simmi is a recruitment consultant, voting in Wolverhampton South West which was once held by Enoch Powell. Narrowly captured by the Tories in 2010, the seat is a key battleground, with the latest round of polling putting the Labour challenger ahead. She hasn't thought much about the election so far but is determined to change that.

The trio don't have a history of following politicians or parties on social media but, as Sakib says, social media has given all of these politicians a platform to reach them. For the campaign, they'll be following the candidates in their constituency, the accounts of local parties and campaigns, and a number of national political figures.

Each thinks social media could have a big effect on how they will vote, if the politicians get it right.

Iram wants clear ideas over political tactics. For Simmi, it'll be politicians responding to Tweets that'll be important, to help her learn what they are really like, and how much they understand what "average Joes" are dealing with.

'More involved'

Sakib agrees, it's all about interactivity: "Whether they'll pay attention or respond... you feel like you can get more involved with what's happening." He's particularly keen to hear what's going on in his own constituency and what will affect people there.

In the coming weeks, we'll be asking them about the type of messages they received, what caught their eye and why. We'll see whether it's politicians, spoof accounts or pictures of cats that made it into their social media streams.

We'll learn about the kind of messages that caused them to think, and maybe to change their mind - and whether it was all worth the parties' efforts.

Beyond the frenzy of the political campaign, one final question is important. At a time of declining party membership and decreasing voter turnout, are these digital platforms a new way of engaging people with politics?