Election 2015: The politics of legitimacy

- Published

Politics is sailing into turbulent constitutional waters. That at least is what the opinion polls tell us.

These waters are not entirely uncharted; politicians have had to navigate the shoals of hung parliaments before. But historical precedent and ancient charts can provide only a rough guide through changing winds and tides. Politics, like the sea, is never the same.

There is before us a bewildering array of possible outcomes if no one party gets a majority. And many of those outcomes could involve some new politics for us all to get used to.

One of the big dynamics of the next parliament, I believe, will be a tension between what is legal, what is constitutional, what is precedented - and what the voters think is right and proper and legitimate.

So here is a list of hypothetical scenarios that could place new demands on the electors and the elected. Some are important; others trivial. The list is by no means exhaustive. But there are some searching questions here to which we have yet to have meaningful answers.

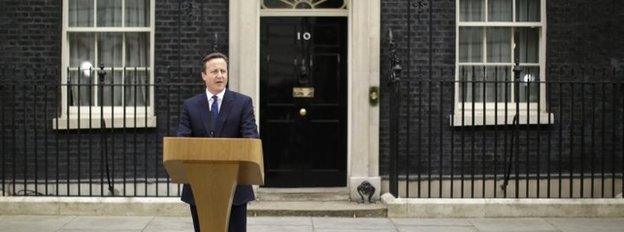

Would voters think it legitimate for David Cameron - if defeated - to remain prime minister while other parties struggle to form a new government? If the Conservatives lose the election, it might take some time for Labour to form a new administration if it does not have a majority. It might have to form a coalition or minority government with the support of other parties such as the SNP or the Liberal Democrats or other parties. That could take some weeks. And all that time the defeated prime minister is obliged by constitutional convention to remain in Downing Street to keep the Queen's government going. His ministers would remain in office too. Five years ago Gordon Brown was desperate to leave Number Ten to avoid accusations that he was clinging on to power. Might voters put similar pressure on a defeated Tory leader to go? Might David Cameron feel honour-bound to leave as soon as possible to respect the wishes of the people?

Would voters think it legitimate for Nick Clegg to remain deputy prime minister if the Lib Dems won significantly fewer votes and seats? The Lib Dems had 56 MPs in the last Parliament. Together with 306 Conservative MPs, they had easily enough votes in the House of Commons to achieve a majority. Many polls suggest the Lib Dems could see their number of MPs halved. But if either the Tories or Labour do well enough to need only one more party to form a coalition, they could do it with 30-odd Lib Dem MPs. And once again Mr Clegg could remain deputy prime minister despite having such a small presence in parliament. Both the Tories and Labour would almost certainly rather do business with the Lib Dems than the SNP. But would voters think it right for Nick Clegg to remain DPM if his party had been so resoundingly rebuffed in the polls? Constitutionally Mr Clegg would have every right to remain in office. But would it be politically acceptable?

Would voters think it legitimate for the Lib Dems or another other smaller party to decide which of the two larger parties should lead the next government? In 2010, it was pretty clear that the Conservatives had done better than Labour. But what if there were to be some kind of a dead heat between the Conservatives and Labour this time around? In that circumstance, the Lib Dems could be in a position to decide which party they could support. Nick Clegg says repeatedly that he will speak to the party with most votes and seats. But he leaves ambiguous what he would do if one party had more votes and another had more seats. His manifesto certainly swung both ways, leaving the door open to working with either Labour or the Conservatives. Would voters think it right for a smaller, depleted party to decide which party governs the whole nation?

Would voters think it legitimate for a party that came second to form a government? The fundamental constitutional principle is that the prime minister is the man or woman who can command a majority in the House of Commons. Normally that is the leader of the largest party. But it would be entirely possible for, say, the Conservatives to end up with most seats and votes but not a majority and yet be unable to form a government if no other parties come to its aid. That might leave Labour as the second largest party forming a government with, say, the support of the Lib Dems or the SNP or another party. This would be entirely proper under the constitution. There are several precedents of this happening before. But it might perplex some voters. The party that came second, that did not have the largest number of votes or seats, would be running the country. Would voters think it legitimate, for example, for a Labour party that came second in England and Scotland to be able to form the government for the whole of the UK?

Would voters think it legitimate for any party to form a minority government in the first place? The prime minister of this party may command the confidence of the House of Commons, not because he has a majority, but because the opposing parties are unable to form a government among themselves and do not want to table a confidence motion and spark a fresh election. But what will voters think of a government that has such little support in the Commons that it struggles to get anything done? We have no culture of minority government in the UK. People may have learned to get used to the new politics of coalition government. But would they go the next step and adapt to the culture of minority government? For example, it would be entirely possible for MPs to defeat a minority government's Budget and Queen's Speech without actually killing the government. One of the key changes of the Fixed Term Parliament Act (FTP Act) is that Budget and Queen's Speech defeats are no longer matters of confidence; the Act says instead that MPs have to vote a government down by backing a specific motion of no confidence. Would voters think it legitimate for a government which had lost its central economic policy to struggle on because the opposition parties chose not to fight an election at that time?

Would voters think it legitimate for a government to engineer a vote of no confidence in itself simply to try to force an election under the Fixed Term Parliaments Act? This is entirely possible and legal under the FTP Act. But it forces an administration to commit legal self-destruction in plain sight. Would voters think this a little odd? Would they punish a government that forced an election upon them in this way?

Would voters think it legitimate for a minority government to be replaced by another administration of a different political colour without an election taking place? The FTP Act says that if a government loses a vote of confidence, there does not have to be a general election straight away. The Act says the parties first have 14 days to try to form a new government before an election has to be held. In other words, voters could see, say, a Labour-led administration replaced by a Tory-led administration without so much as a single vote being cast. That is the law. But it is a law which I imagine few voters know about. Would they find it legitimate? I imagine many voters would be horrified by the idea of power being traded around at Westminster with barrels of political pork being offered to bribe the smaller parties into one camp or another. The idea of the Westminster parties swapping power among themselves without consulting the voters might add to the already gaping void between politics and the people.

Would voters think it legitimate for a party such as the SNP that has a geographical focus on one part of the UK to have a large say in the government of the UK as a whole? One possible outcome of the election is that the SNP do well enough in Scotland to have a big say in any minority government at Westminster. Some of their policy priorities are focused on Scotland, such as giving more powers to the Holyrood parliament. But other policies - such as opposing the renewal of Trident nuclear weapons - would affect the whole of the UK. Would voters in England and Wales and Northern Ireland believe it legitimate for one part of the country to hold such a big say over such a UK-wide issue? This is the issue that was raised by David Cameron on the Andrew Marr show. He said: "This would be the first time in our history that a group of nationalists from one part of our country would be involved in altering the direction of the government of our country, and I think that is a frightening prospect, for people thinking in their own constituencies is that bypass going to be built, will my hospital get the money it needs? Frankly, this is a group of people that wouldn't care about what happened in the rest of the country. The rest of the United Kingdom, England, Wales, Northern Ireland, wouldn't get a look in". Now, voters in Scotland might retort that many there have long believed it illegitimate for English-dominated parties like the Conservatives to impose their policies on Scotland. But there is an interesting question here. If the SNP replace the Lib Dems as the third largest party at Westminster, they would have every democratic and constitutional right to play a role in the government of the UK in a hung parliament. But would the voters think it legitimate?

Would voters in Scotland think it legitimate for the SNP to win a landslide north of the border only to see another Lib-Con government or a new Lib Lab government formed at Westminster? Constitutionally, the SNP would have no automatic right to play a role in the next government if other parties chose to work together to form an administration. But would SNP-supporting voters in Scotland feel short changed; that the transformation of Scotland's politics and the new phalanx of SNP MPs at Westminster had come to naught?

Would voters think it legitimate for David Cameron to remain prime minister while no longer remaining leader of the Conservative Party? Mr Cameron told me in his kitchen that if he was returned to Downing Street for a second term, he would not serve a third. His aides insist he would serve every day of that second term. But this has led to some confusion. Many commentators say the Tories could not go into the 2020 election with one leader and then change their leader immediately after votes have been cast. So the suggestion has been made that Mr Cameron could remain prime minister up to the election but he could stand down as Tory leader, say, a year earlier to allow a successor to be elected. This is not without constitutional precedent. Prime ministers do not have to be party leaders. They just have to command the confidence of the House of Commons. For example, Winston Churchill was prime minister for six months in 1940 while Neville Chamberlain remained Tory leader after his resignation from Downing Street. John Major remained Prime Minister in 1995 when he briefly resigned as Tory leader to hold a "put up or shut up" contest with John Redwood.

Thus, then, some questions about what may or may not be seen as legitimate in the new politics of the next parliament. The optimists say, fear not, look how quickly the people of Britain adapted to coalition government in 2010. The warnings of disaster proved unfounded. The pessimists fear a further dislocation between parliament and the people if things are done in their name they do not understand and believe to be unfair.