Election 2015: Manual sets out the rules for a hung parliament

- Published

Can I recommend some reading? The Cabinet Manual is not a furniture assembly guide. Instead, it is the clearest route-map we have to what will happen if no single party wins an overall majority at the general election.

And with the two main parties deadlocked in the polls and a hung parliament looking increasingly likely, the document will be a crucial reference point.

The Cabinet Manual will guide the actions of parties trying to form a government, the civil servants who may advise them and the back-channel discussions between the parties in Parliament, No 10 and Buckingham Palace in the days after 7 May.

You can read it for yourself, external on the Cabinet Office website.

BBC News Timeliner: The indecisive election

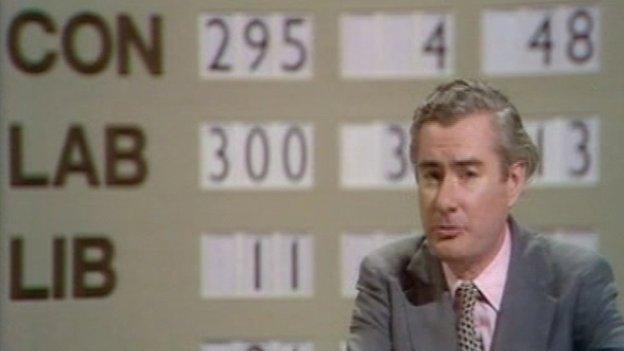

The 'crisis election' of February 1974, held amid miners' strikes and the three-day week, produced a result that was far from conclusive.

Watch video from the vaults on the BBC News Timeliner, external

Sticky predicament

So what is this manual? Shortly before the 2010 election, the then Cabinet Secretary Gus O'Donnell produced a document that clarified the rules, conventions and laws that steer the operation of government.

Drawing on work that had been done ahead of a general election in New Zealand, the document also set out what should happen in the case of an inconclusive election result.

The draft Cabinet Manual was the result. It was written in consultation with constitutional experts, officials from the Ministry of Justice, the Cabinet Office, No 10 and the Queen's Private Secretary.

The manual was drawn up by former head of the civil service Sir Gus O'Donnell

A priority was to protect the Queen from any sticky constitutional predicament in the event of a hung parliament.

It was a very significant step for Whitehall to take. The UK doesn't have a written constitution. It is a patchwork of precedents, unwritten rules and conventions that depends ultimately on the "good chap" theory of government - in other words, its participants playing the game decently.

But what if they don't? What if the murky, contestable conventions of the past lead to constitutional crisis, particularly with a frenzied media pronouncing winners and losers and demanding an immediate resolution?

Commons confidence

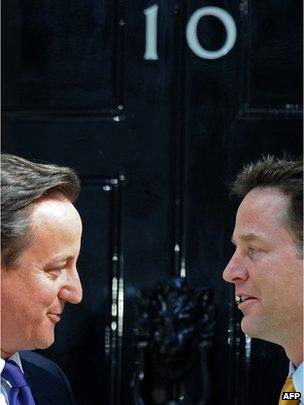

The Cabinet Manual aims to provide precise answers to very big and politically contentious questions. And during the five days of negotiation in May 2010 the draft manual funnelled the main participants through a smooth transition of power.

The guide had done its stuff. It was then updated and published in its current form in October 2011. And the 10 paragraphs on government formation following a hung parliament will be the go-to guide for what might unfold after 7 May. Its main points (paraphrased by me) are these:

A government must be able to command the confidence of the House of Commons

Prime ministers hold office unless and until they resign. If the prime minister resigns on behalf of the government, the monarch will invite the person most likely to command the confidence of the Commons to become prime minister and form a government. So, the Queen has no effective power over appointing a new PM

If an election does not result in an overall majority for a single party, the incumbent government is entitled to wait until the new Parliament has met to see if it can command the confidence of the House of Commons BUT should resign if it becomes clear it cannot and there is a clear alternative

The political parties can hold discussions between themselves to establish who can command the confidence of the Commons and they can choose to have support from civil servants

If no single party has an overall majority, there are three main options for the sort of government that could be formed. A formal coalition, made up of two or more parties which usually includes ministers from more than one party; an informal agreement, in which smaller parties would support a government on major votes in return for some concessions; or a single-party minority government, where one party goes it alone and tries to survive vote-by-vote supported by a series of ad hoc arrangements.

So that, in brief, is what the manual says. It sets out the principles the parties should follow.

Myths and Reality

But it will not stop politicians saying quite different things before and after polling day. For instance, Nick Clegg has said a government formed by the party that came second (in terms of seats in the Commons) would lack "legitimacy" and that voters would question its "birth-right".

But the only test for whether a government can be formed is whether it has the confidence of the House of Commons. In other words, can it assemble the votes to get a Queen's Speech passed, the first test of a government's mandate?

After the 1923 election, the Tories were the largest single party in the Commons but a minority government was formed by Labour, which was the second-largest party.

Constitutionally, there is no rule that the party with the largest number of seats has a right to form a government. Mr Clegg also said the party with the largest mandate should be able to negotiate first.

The Cabinet Manual is clear the sitting Prime Minister has the right to see if they can cobble together a Commons majority but that does not prevent other parties talking to people at the same time. That happened in 2010, although unlike then there are likely to be more parties involved in the negotiations.

Now the magic number of seats a party (or group of parties) needs to have in the Commons is 323. And while the Cabinet Manual provides a very useful guide, there is still plenty of scope for this being a messy and fraught fight for power, particularly if rival camps have very similar numbers and neither is prepared to concede.

Another big difference between May 2015 and May 2010 is that the SNP may well be the third largest party in Westminster after polling day, making them essential to any negotiation - whatever the parties say now.

And despite the constitutional clarity provided by the manual there will be other powerful currents at play: questions of legitimacy, the mood of the press, the verdict of opinion polls and the appetite of party leaders to write their own rules.