Election 2015: When will it all be over?

- Published

Nick Robinson examines what could happen if there is a hung parliament after the election

Don't worry. Not long to go. The election that never seems to end will be over by next Friday… or maybe it won't.

On the morning after the night before, you might imagine that you won't have to hear from that seemingly endless parade of political leaders anymore but, and I'm sorry to have to break this news to you, you may be wrong. Very wrong.

If (and it is still an if) the opinion polls don't budge, as they have stubbornly refused to do not just for days or weeks but many, many months, the people may have spoken but no-one will quite know what it is that they have said. There will be no clear winner. No instant answer as to whether David Cameron stays in Number 10 or calls the removal men.

So, what happens then? That's something which the men you rarely see (and they are all men) who wield enormous power behind the scenes have spent an awful lot of time thinking about.

They are prepared not just for days of haggling but weeks. The man who was in charge of the negotiations which produced the coalition five years ago, the former Cabinet Secretary Lord O'Donnell, says that those talks were a "piece of cake" in comparison with what his successor, Sir Jeremy Heywood, may face on 8 May.

BBC News Timeliner

Many echoes of the current election campaign can be found in those of the past forty years, as a trip through the BBC archive ably exhibits.

Watch video from the vaults on the BBC News Timeliner, external

Think again

The reason's simple. Politics has got much more fragmented. So, five years ago the question was relatively simple - what sort of deal would the Liberal Democrats do and who would they do it with? Just three parties were involved.

After this election, it may be that not only can neither the Conservatives or Labour form a government on their own, but also that they couldn't do so with the help of the Liberal Democrats.

So the decisions of all those leaders who lined up in that big election debate - of the SNP, Greens, Plaid Cymru and UKIP - plus those that didn't - such as the DUP - will count.

Now, you might assume that the party that almost wins - that gets the most MPs and the most votes - would have the first chance to form the next government. Think again.

Any party leader can try to do the deals needed to get a majority of MPs to back them in the House of Commons.

Who has the votes needed to get their proposals for new laws passed? That - and that alone - is what determines who becomes prime minister. The ultimate test of that is who can persuade the Commons to back their agenda as set out in what's called the Queen's Speech.

Gordon Brown was urged to stay in Downing Street until a deal was done

The last time the party that came second ended up running the country was 1924, when Ramsey MacDonald led the first ever Labour government with the support of Herbert Asquith's Liberals.

Many people think that's what could happen in 2015. If Ed Miliband doesn't have enough Labour MPs to govern on his own surely, many say, he'll be able to do so with the support of the Liberal Democrats and the SNP? Maybe, but not necessarily.

David Cameron knows that it is his duty to stay on as prime minister until he is clear he can't form a government and Ed Miliband can.

If he were ever to forget that, he will be reminded again and again by the country's top civil servant - the cabinet secretary - and the top official at the Palace, Sir Christopher Geidt.

It was they who urged Gordon Brown to stay on at Number 10 - to continue the work of Her Majesty's ministers - even as the Tory press were unfairly accusing him of "squatting" there against the wishes of the British public.

Testing opinion

Indeed, even if Labour and the SNP together could have a majority, David Cameron would be totally within his rights to refuse to quit until there is a deal that proves that Ed Miliband has the votes he needs.

Indeed, he would have the first chance to table a Queen's Speech to test opinion. It would be risky. He might lose, just as his Tory predecessor Stanley Baldwin did back in 1924. What Ramsay MacDonald said to the Commons more than 90 years ago could be a guide to what Ed Miliband may want to say in a few weeks time:

"No prime minister has ever met the House of Commons in circumstances similar to those in which I meet it...

"I propose to introduce my business, knowing that I am in a minority, accepting the responsibilities of a minority, and claiming the privileges that attach to those responsibilities.

"If the House on matters non-essential, matters of mere opinion, matters that do not strike at the root of the proposals that we make, and do not destroy fundamentally the general intentions of the government in introducing legislation - if the House wish to vary our proposition, the House must take the responsibility for that variation - then a division on such amendments and questions as those will not be regarded as a vote of no confidence."

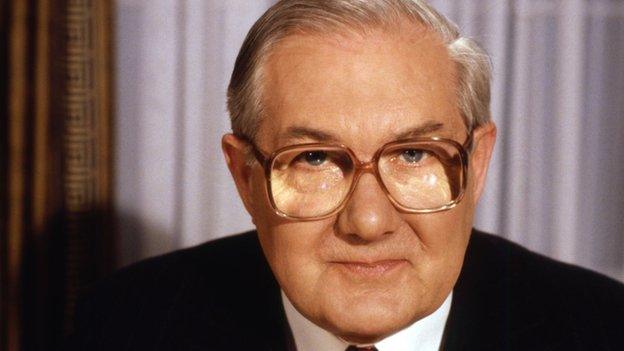

Jim Callaghan faced a number of knife-edge votes

Conventional wisdom has it that a minority government is weak. How could it not be, as it is forced day in, day out to look for deals simply to survive?

People who are old enough recall the dog-days of Jim Callaghan's Labour government in the late 70s, which suffered night after night of knife-edge votes in which the sick and dying were ferried in and out of the Commons to keep their political project alive.

There are, though, happier lessons from more recent history. Alex Salmond's first Scottish government won just 47 seats out of 129 in 2007 - one more than Labour - but it lasted a full term. In Canada, whose parliamentary system is modelled on our own, Stephen Harper led a minority government for five years.

The cabinet secretary has been examining the ways in which a minority government can get things achieved without needing new legislation and, therefore, parliamentary support (eg being creative with existing laws, risking court action, relying on issuing guidance or a so-called "nudge" and, of course, by spending money).

Let's remember, the polls may yet move. There may be a clear winner. We may see a good old-fashioned majority government formed next Friday.

And yet, and yet… if you think it's all going to be over once all the votes have been cast, you may want to think again.