Election 2015: Where next for Labour?

- Published

There are, believe it or not, some scraps of comfort for Labour in amongst the wreckage of the election results.

With an economic recovery in full swing, unemployment falling and real wages finally perking up, the Conservatives had a powerful and optimistic message to sell.

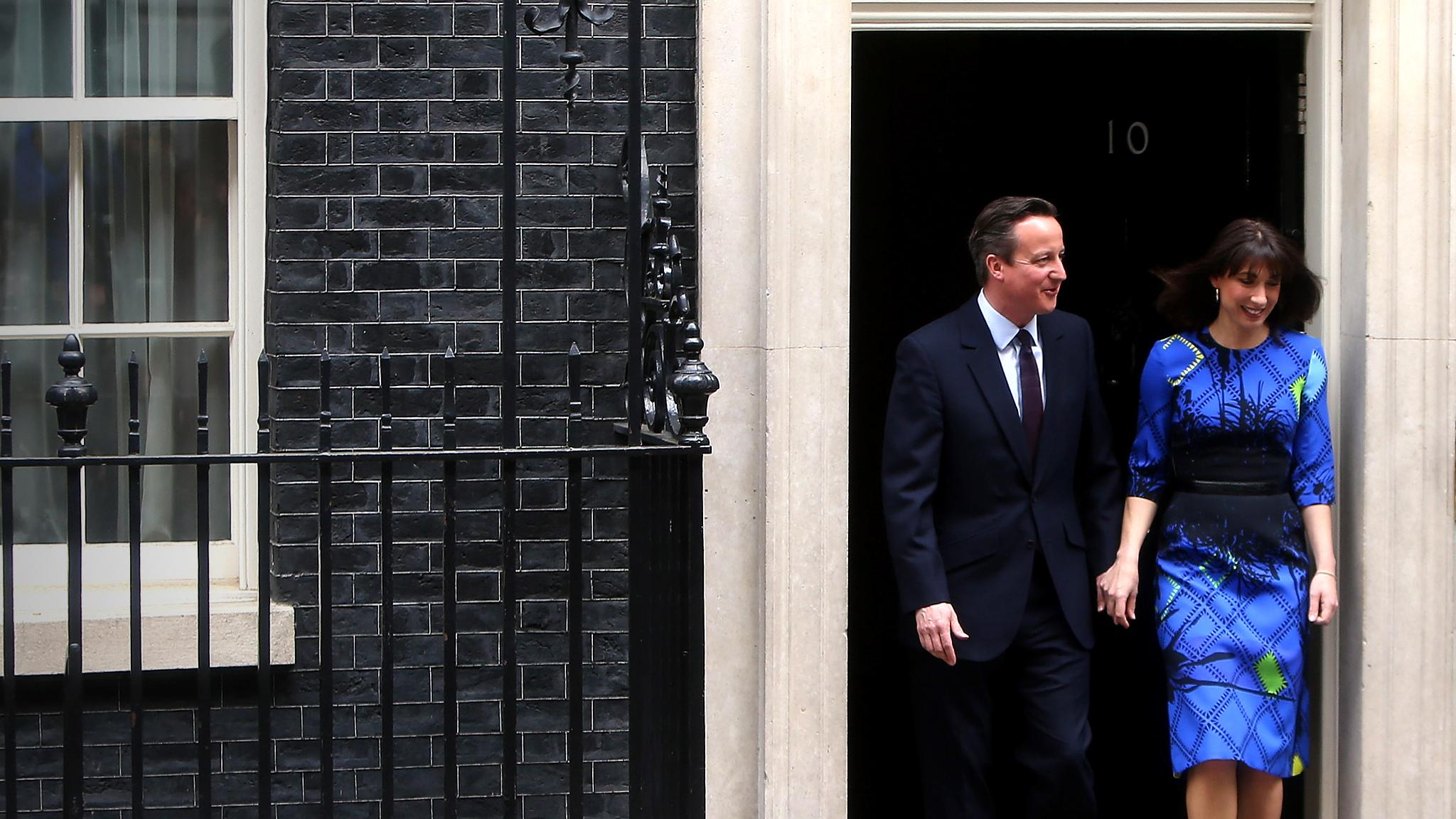

However much Labour supporters spat about him, David Cameron was a well-liked leader, with a hefty incumbency advantage.

And from the left you can expect much vitriol to be poured on to the Tory press, much of which abandoned all and any pretence of objectivity and walked through the campaign hand-in-hand with Conservative party HQ.

Why can Labour take comfort from any of the above?

Because another time the economy may not be so ruddy, the electorate may be tired of a Conservative leader, the press may be less influential or more biddable.

But it is, to say the least, scant comfort.

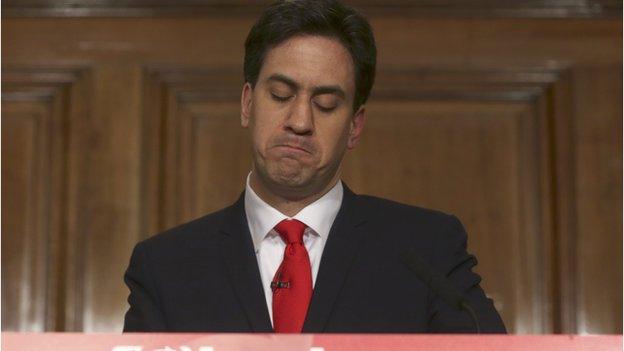

Ed Miliband: ''It is time for someone else to take forward the leadership of this party''

Step back from the night and the campaign and the structural challenge for Labour that emerges from this night is astonishing.

Labour is now brutally squeezed geographically and ideologically; Scotland is solidly SNP yellow; the south of England, bar London, pretty solidly Conservative blue.

To lean left so as to appeal to former supporters in Scotland would imperil what remains of the centre-ground supporters who were so crucial to the victories under Tony Blair.

Tony Blair's Labour Party won in England when it occupied the centre ground. He was, of course, aided by a staggeringly inept Conservative opposition.

The appeal to those who wanted to get ahead, as well as those who traditionally voted Labour, made Blair's Labour seem like the natural party of government. Labour has to rediscover that magic potion.

But to chase after the 'New' Labour voters of southern England may only alienate further Scottish voters clearly deeply unhappy with the way the Blairite party developed.

Which way to jump?

Given the scale and nature of the defeat in Scotland, the temptation for Labour must be to politically abandon its former fiefdom so as to concentrate on re-taking English seats. But it would be a brutal political amputation.

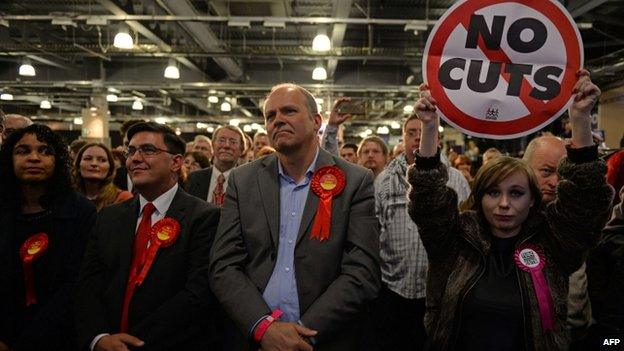

There is (even) more bad news for Labour. Throughout the campaign Labour had the upper hand on the ground.

The Conservative party is shrunken at the roots, unable to mobilise the numbers for street-by-street campaigning.

The so-called 'ground-war' was dominated by Labour, and voters in marginal constituencies reported much more contact with Labour activists than with Conservative counterparts.

And it appears to have made no difference at all.

As Labour unveiled policy after policy, the Conservatives stuck rigidly to their two messages - that the economy was safe only in their hands, and that Labour would be held to ransom by the SNP.

In this "air-war", assisted by the pounding guns of Tory-supporting newspapers, the Conservatives triumphed, and all the leaflets and door-knocking in the world appear to have achieved nothing.

The defeat in 1992 led - eventually - to a very different Labour party; a party that cast aside its old politics, and reinvented its campaign machine.

That kind of reappraisal again faces an exhausted party. Against the backdrop of swirling nationalism, it is for Labour's supporters a depressing and daunting task.

- Published8 May 2015

- Published8 May 2015