Reality Check: What if Scotland controlled its taxes?

- Published

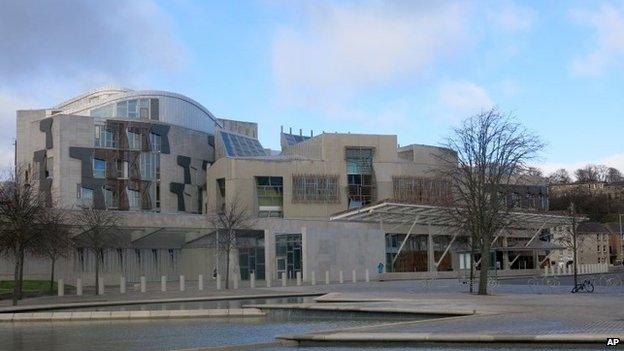

What would happen if the Scottish Parliament got full fiscal autonomy?

Excuse the jargon. What it means is that Holyrood would have control over all of taxation in Scotland.

For the shared costs of continuing to run the United Kingdom, it would pay Whitehall a portion of the takings - for defence, the Foreign Office, the Treasury and shared regulators such as Ofcom and Ofgem.

Those in favour say such a move would respond to public demand for more powers at Holyrood. They say it would provide the levers of power over economic policy that could help grow the economy faster. That includes targeted business tax breaks.

Those against say that it would leave a large gap in the nation's finances - a £7.6bn shortfall next financial year over and above a share of the deficit that the UK is already running.

So who's right?

Let's see where that number comes from. The £7.6bn number, cited by Labour and others, comes from the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) and is based on the latest projections from the Office for Budget Responsibility.

Published with the Budget on 18 March, this reflects a sharp fall in forecast revenue from offshore oil and gas.

To recap, production levels have been falling, and profits (on which tax is levied) have been hit by both fast rising operating costs and the falling oil price.

The OBR is projecting an average of £700m in offshore revenue for each of the next few years.

That may sound a lot, but it's a big fall from the bumper revenue we've seen in recent years in the notional share that might have gone to Scotland if it had control of oil revenue in its own waters.

Since 2009-10, that annual figure has been £5.7bn, £7.5bn, £9.7bn, £5.2, £4bn and £2.2bn.

At the same time, Scotland's onshore (non-oil) tax revenues have been very close, per head, to those for the UK as a whole.

And Scottish spending has been about 11% per head higher, partly through more welfare spend, more expensive health challenges and transport in remote areas.

So those oil figures, added to onshore tax receipts, have been important to explaining how Scotland could have paid for its higher levels of spending. Its deficit has looked smaller than that of the UK in a couple of recent years.

With much smaller projected oil revenue, however, the scale of the deficit gets bigger.

Measured as a share of Gross Domestic Product (which is how economists reckon it is best to compare countries of different sizes), the notional figures show Scotland has had some years of smaller deficits due to the strong oil revenue.

But with lower oil revenue forecasts, the UK deficit for next year looks like 4% of Gross Domestic Product, while the Scottish deficit would be 8.7%.

Is that manageable? Well, if it's any guide, the rules for membership of the euro currency say each country's deficit should be below 3% of GDP (not that many have been sticking to that rule, recently).

Public spending

Under these forecasts, the UK would continue to run a deficit, next year expected to be about £75bn.

Scotland's share of that, by population, would be less than £7bn. But if it had control over all its tax resources, Fiscal Affairs Scotland calculates that the deficit would be £14.2bn.

The difference between the share of UK deficit and the stand-alone deficit for Scotland would be nearly £8bn. That is the equivalent of the IFS figure of £7.6bn, the difference resulting from different assumptions.

Fiscal Affairs Scotland looked at future projections too, as the squeeze is applied to public spending, under the coalition government's plans.

By 2018-19, that plan would put the UK economy into a small surplus. In the same year, Fiscal Affairs Scotland reckons that Scotland would be running an £8.2bn deficit.

There is another way of looking at this, of course. The Scottish government does not see itself as inheriting exactly the same position that the UK currently has.

Business investment

It wants those taxation powers to help grow the economy faster. It has set a target for growing exports by half, bringing business investment up to the levels in similar economies, and boosting the rate at which the Scottish economy becomes more productive.

If it were to hit all these targets, the Scottish government reckons that would boost employment and profitability, so that tax revenue would be £3.5bn higher within 10 years.

The block grant which comes to Holyrood from the Treasury in London would be replaced by full fiscal autonomy.

But the point at which that happens is the subject of political dispute. The Scottish government says it would be over time, smoothing the transition phase.

Because these are forecasts, of course we cannot know if that is how they will turn out. Indeed, it's near certain that almost all forecasts will be proven wrong.

But if the economy can't be made to grow that much faster, if oil revenues don't bounce back, and if there are no other ways found of boosting tax revenue, then the continuing gap between revenue and spending in Scotland would require either tax increases or spending cuts - or it would mean more borrowing, though that has consequences for taxation and spending in future years.

Election 2015 - Reality Check

What's the truth behind the politicians' claims on the campaign trail? Our experts investigate the facts, and wider stories, behind the soundbites.

Read latest updates or follow us on Twitter @BBCRealityCheck, external