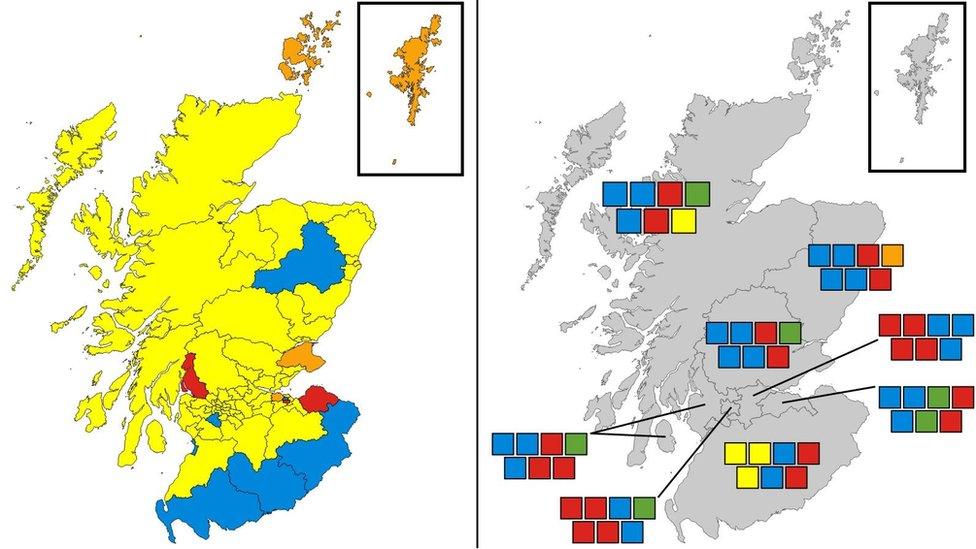

How the system played its part in the Holyrood 2016 result

- Published

The SNP celebrated a third consecutive term in government in Thursday's elections

The SNP is celebrating a third successive win at Holyrood - but unlike 2011 it failed to bag a majority. Here, I take a look at Scotland's electoral system and why the Nationalists recorded the numbers they did.

Scotland's latest cohort of MSPs are arriving at Holyrood to gear up for the new term, which will see the SNP back in government.

The party followed up nine years in government by winning by far the largest number of seats in last Thursday's poll, and leader Nicola Sturgeon will continue with a personal mandate as first minister.

But despite this, there is a mild degree of grumbling among some SNP supporters over the slightly smaller team of MSPs returned. With the loss of six seats, they will be forming a minority administration, having enjoyed a majority for the last five years.

This note of disgruntlement comes down to two factors....

Scotland's relatively labyrinthine electoral system

The sky-high level of expectation people have developed around the party's electoral fortunes.

Since the 2014 independence referendum the SNP has been an absolute juggernaut. Its membership has swelled to more than 116,000, the party's conferences and even manifesto launches are more like rock concerts than sober discussions of public policy.

The system broke in 2011

It smashed its rivals in the 2015 general election, coming near to sweeping the entire country, and every poll predicted a second outright majority at Holyrood on Thursday. As we now know, this was not to be.

In truth, the position the SNP occupied prior to polls opening was already unprecedented. Holyrood isn't meant to have a single party commanding an outright majority - the way the electoral system is set up works very effectively against this.

So if the 2016 results might seem like a relative disappointment for the SNP, it is because whether by force or fluke, they broke the system in 2011.

Nicola Sturgeon has won the personal mandate she was seeking to be first minister

Holyrood's Additional Member System strives for a model of proportional representation. While the Westminster model of first past the post is geared towards strong governments toting stonking majorities, Holyrood's system seeks balance and fairness between parties.

And in this regard, it appears to have worked to perfection; on Thursday, the SNP won just under half of the votes cast, and will head back to Holyrood with just under half of the MSPs.

There's an obvious contrast with the 2015 general election; there, the SNP won 50% of the vote in Scotland, and were rewarded with 95% of the seats on offer. Labour, the Conservatives and the Lib Dems netted a solitary MP each, despite their wildly differing performances on the night of 24%, 15% and 7.5% respectively.

These are the kind of quirks the complex calculation at the heart of Holyrood's system - the D'Hondt method, named for the Belgian mathematician who created it - is designed to iron out.

In simple terms (avoiding entirely any talk of "quant = V / s+1"), the more seats a party wins in the 'first past the post' constituency races, the less they are likely to collect some in the regional list.

'Both votes SNP' campaign

An example is Glasgow - the SNP swept all eight constituency seats, thumping Labour in what was once their back yard. This meant they were already handsomely represented in the area, leaving Labour, the Tories and the Greens to share out the list seats according to their share of that vote.

It would have been almost impossible for the SNP to add to their tally in Glasgow - hence some supporters of other pro-independence parties, such as Rise, Solidarity, and the Greens, campaigning hard for list-vote support from SNP constituency-voters.

However, the SNP didn't want to run any risks with their campaign. Because if somehow Labour had held one or two of the Glasgow constituencies, they would want to have a strong chance at picking those seats up again on the list. Hence "both votes SNP" came to be plastered across every bit of their campaign material.

The electoral stars aligned to land an unprecedented majority for the SNP in 2011

Now, in the Holyrood election just past, it was widely expected that the SNP would win enough seats from the 73 constituencies up for grabs to form a majority outright, without having to rely on the allocation of MSPs from the regional lists.

They did not. And when it came down to it, even with a strong showing in the list vote, it simply wasn't possible for the formula to spit out enough Nationalist MSPs for a majority.

In 2011, the stars aligned in just the right way for the SNP. They were able to bring home 16 list MSPs on top of the 53 they won from constituencies.

Viktor D'Hondt himself may have struggled to explain it, but in basic terms the placing of their constituency wins balanced out perfectly with enormous support on the lists to return relatively large numbers from both ballots.

That election "broke" the system; the SNP made off with a majority of seats (53.49% to be precise) despite only winning 45.39% of constituency votes and 44% of the regional list ones.

This time round, a slightly reduced 41.7% of the vote only translated into four list MSPs - although (and indeed because) the 59 constituency seats won with 46.5% of the vote is itself a Holyrood record.

Ruth Davidson's Conservatives frustrated the SNP in a number of seats

The list system will take some flak from the "both votes SNP" crowd, but at the end of the day the party's failure to sew up the constituency vote proved equally decisive.

The SNP took a good number of seats, annihilating Labour in Glasgow in particular. But they also lost some - and in key areas.

Willie Rennie and his Lib Dems frustrated them, swatting away challengers in Orkney and Shetland with ease despite the controversy of the Alistair Carmichael affair, before actually seizing SNP seats in North East Fife and Edinburgh Western.

The Tories too mounted successful raids, with Ruth Davidson pinching Edinburgh Central and Alexander Burnett toppling Dennis Robertson in Aberdeenshire West - both surprising results.

Ms Davidson's party also took seats from Labour which the SNP considered themselves strongly in the hunt for, in Dumfriesshire and Eastwood.

The placing of these seats, nestled among great blocs painted SNP yellow, meant the nationalists had relatively little hope of gaining them back on the list vote.

The only region of the country where the SNP didn't win the majority of constituency seats was South Scotland - and there they picked up three list seats. This swung the equation against them when it came to dishing out list MSPs.

The placing of the constituency seats the SNP did not win left it hard for them to win them back on the list

Looking at exactly where the six SNP seats from 2011 were lost, Lothian was the key area.

Here, the SNP lost constituency seats to the Tories, Labour and the Lib Dems, but were unable to win any of them back on the list.

The fact the party won five of the eight constituency seats meant they faced little hope of gaining any of the three lost back through the list, and this was extinguished by an 11.3% surge in the Tory vote and a 3% jump in the Green one, with both of those parties gaining.

Patterns repeated

In Highlands and Islands, no constituency seats changed hands, with the Lib Dems holding two and the SNP six, But the SNP's support on the regional list fell by 7.8%, while the Tory and Green votes again jumped, meaning each of those parties picked off an SNP list seat.

In Mid Scotland and Fife, the SNP lost North East Fife to the Lib Dems but gained Cowdenbeath from Labour. But on the list their vote dropped by 3.9%, while the Tories gained by 11% and the Greens by 1.9%, meaning the single SNP list MSP was lost.

The same pattern was repeated in North East Scotland, where the SNP lost a single constituency seat to the Tories and another on the list, thanks to a 13.9% jump in the Tory list vote.

So the double-digit increase in the Tory list vote, partnered with a gentle decline in the SNP's support and a small uptick in backing for the Greens, meant the list vote could not make up for the losses of constituency seats in these key areas.

- Published9 May 2016

- Published7 May 2016

- Published6 May 2016