Election 2017: If more young people actually voted, would it change everything?

- Published

Young people prefer Labour over the Conservatives, according to opinion polls. But the majority don't vote. So if they did, what would happen?

The turnout gap

In the 2015 general election, the gap between old voters and young voters was massive.

Just 43% of 18-24-year-olds went to the polls, compared with 78% of people aged 65 or over, according to Ipsos Mori. (To estimate how many old and young people vote at elections, you have to look at opinion polls). That's a huge gap of 35 percentage points.

There's been a similar gulf for the past 20 years, but it wasn't always like that.

As recently as 1992, the gap was just 12 percentage points. Then, 63% of 18-24-year-olds voted. The old aren't voting more now - but the young are voting far less.

In some ways, the low turnout isn't surprising. Young people are mobile and many are students who live away from home - groups which have among the lowest levels of voter registration, according to the Electoral Commission. They are often voting for the first time, so haven't developed a habit, unlike many older people.

Young people with quite high levels of political engagement also often distrust the established political parties, external.

But young people face a dilemma. Groups with low turnouts tend to be of less interest to politicians who want to be elected.

"It's a no-brainer. Why spend time chasing non-voters rather than concentrating all your energy and effort on those who do vote," says David Cowling, a political opinion polling specialist at King's College London.

But if young people turned out like old people, and 78% of 18-24-year-olds had voted in 2015, that would have equated to almost two million extra votes.

"If two million more 18-24-year-olds voted in elections do we really think that issues like housing, low paid, insecure jobs and student fees would not immediately move up the political agenda?" says Cowling.

The party preference gap

Polling consistently shows that young people are more left-wing than older people. So if they were as eager to vote as pensioners, would Labour have a better chance of winning the election?

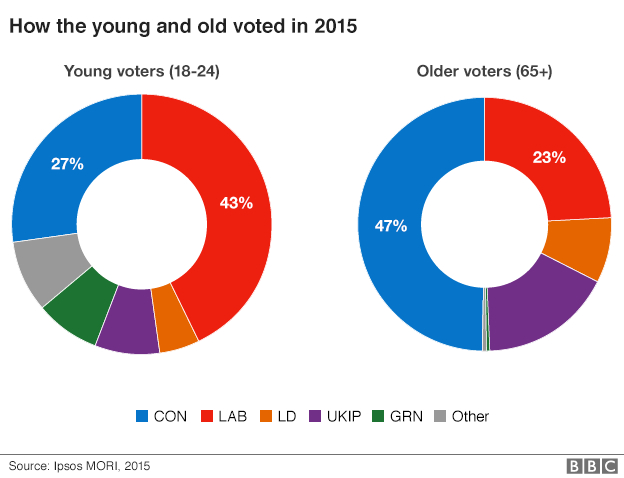

In 2015, 43% of 18-24-year-olds who cast their ballot voted for Labour, while 27% voted Conservative, 8% UKIP and 5% Lib Dem.

By contrast, 47% of voters aged 65 or over cast their ballot for Conservative, 23% voted Labour, 17% UKIP and 8% Lib Dem.

A recent poll , externalof nearly 13,000 people by Yougov suggests 2017 is no different, with Labour 19 percentage points ahead among 18-24-year-olds and the Conservatives 4 percentage points ahead among the over 65s.

Cowling says there is some truth to the "cliche" that people become more right-wing as they grow older. But "it is not some iron law of human nature" as Labour could not have secured its massive 1997 victory without the support of millions of older voters.

He is also sceptical about the youth appeal of Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn.

"Labour talk a big game in terms of Mr Corbyn's personal attraction to young voters, as well as their attraction towards more radical Labour policies in this election. But I see little evidence of any significant shift to Labour among young voters compared with previous elections, nor any greater enthusiasm to vote in 2017 than in previous elections," he says.

So what would happen if 18-24-year-olds turned out like pensioners, but kept their voting preferences?

We've already established a scenario where a turnout of 78% of 18-24-year-olds leads to an extra two million votes.

Assuming the two million extra votes are spread out among parties in the same proportions as the 2.5 million actual votes - a big assumption given it's difficult to predict the intentions of people who don't vote - all the parties would benefit, but Labour would get the biggest boost. They would receive an extra 860,000 votes. The Tories would gain 540,000 votes.

Overall, that would lead to a modest rise in the share of the vote for Labour, and a modest fall in the share of the vote for the Conservatives. But it would be less than 1% of the vote.

This might not sound like a lot, but it could mean five to 10 seats transferring from Conservative to Labour. And, in a tight election such as 2015, when the Tories ended up with a majority of 12 seats, it could make a big difference.

"We should be careful about our predictions but it seems the potential extra two million young voters could have changed the outcome of 2015, robbing the Conservatives of their fragile majority and forcing them to soldier on as a minority government or entering another coalition," says Cowling.

"In a close election every vote counts."

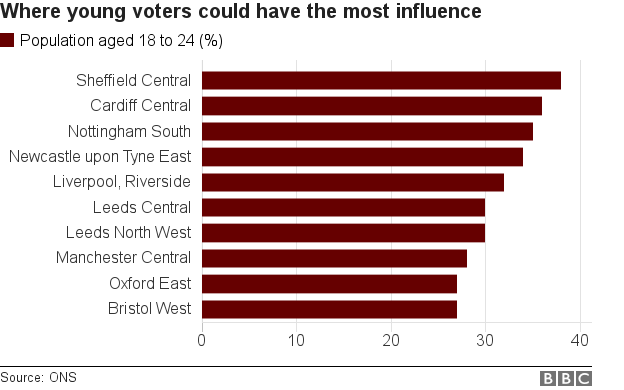

The figures assume that the extra votes are spread evenly across the country, but in real life, that is unlikely to be the case, as young people tend to live in more urban areas, and cities are more likely to vote Labour anyway.

In fact nine out of the 10 seats where young voters are the greatest share of the population, such as Sheffield Central and Cardiff Central, were won by Labour in 2015.

So a higher turnout among young voters could mean a slightly bigger share for Labour, but with many of those extra votes piling up in seats that the party would expect to win anyway.

Grey power

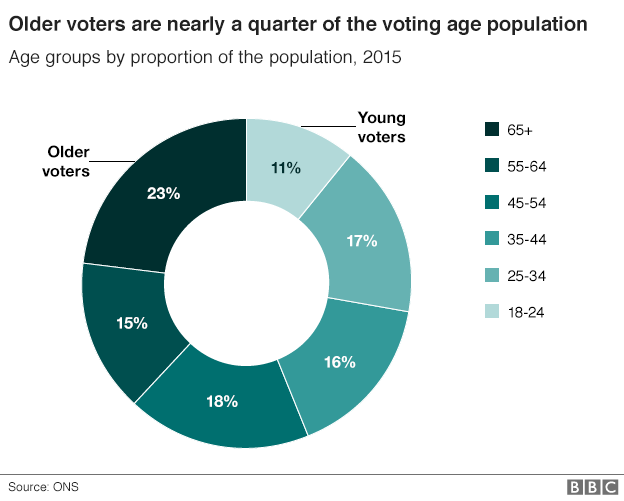

There is also another factor that makes it harder for young people to change the outcome of the election - the sheer volume of older people.

In 2015, there were 5.7 million aged 18-24-years-old in Britain, according to the Office for National Statistics. By comparison, there were 11.3 million people aged 65 and over.

So on numbers alone, the pensioners win out.

Even if we look at a larger group of younger people - 18-34-year-olds, which totalled 14.3 million people in 2015 - and apply the 78% turnout figure to them, it would still lead to only a modest rise in Labour's vote share. About 1%. Again, this could equate to about 10 seats.

That's because although there would be an extra four million votes by 18-34-year-olds, the 25-34-year-old age group is much more evenly split between Conservatives and Labour. In 2015, 36% of 25-34-year-olds who cast their ballot voted for Labour, while 33% voted Conservative.

The (Bre)X(it) factor

The 2017 general election has been dubbed the Brexit election, and yet how much impact the result of the EU referendum will have on the way people vote is relatively unknown.

Once again, age was a dividing line in the 2016 EU ballot. About 75% of 18-24-year-olds voted to Remain in the EU, while 60% among those aged 65 and over voted for Brexit.

How many young people turned out to vote is less clear, with polls suggesting a mixed picture.

There were also three million extra voters in 2016, compared with the 2015 general election, according to Cowling. Who they are is a mystery, but he suspects they were not made up of young Remainers in large part.

It remains to be seen whether, voting appetites whetted, those additional voters will return to polling stations in 8 June. And, if they do, what difference they could make.

Data journalism by John Walton and Daniel Wainwright.

Methodology

Figures from Ipsos MORI and the ONS were used to estimate how increased turnout among 18-24-year-olds might have had an effect on the 2015 general election. MORI's data was used to estimate the turnout of different age groups as well as which party they supported. The data from the ONS was then used to calculate the number of voters in each age group.

In 2015 there were fewer than six million 18-24 year-olds in Great Britain, using a turnout figure from MORI of 43% this would give a rough figure of under 2.5 million actual voters in that age band. If their turnout was then boosted to match that of the over 65s (78%) this creates an extra 2 million voters.

It was then assumed that the voting preferences of the imagined new voters were the same as that recorded by MORI for those in their age group who did vote. This gives all the parties a boost in voters, but due to its popularity with young voters in MORI's 2015 data in this scenario the Labour Party would have benefited the most.