Election 2017: What jobs do UK workers actually do?

- Published

Politicians of all parties spend election campaigns fighting for the votes of what they call "ordinary" or "hard-working" people.

There are record numbers of people in work in the UK, but what exactly do they do and what might be on their minds when they head out to vote?

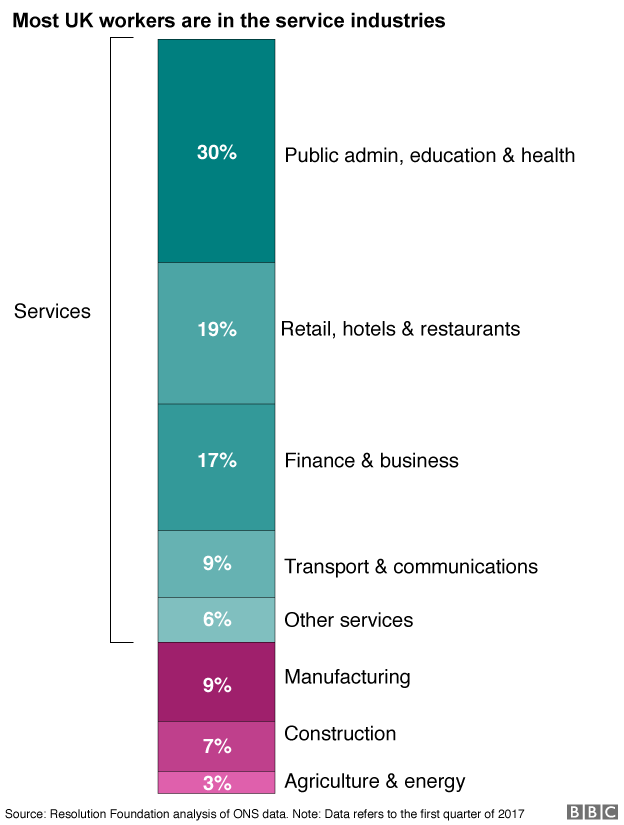

A nation of service industry workers

When politicians want to appeal to working people they tend to don hard hats and head to factories or construction sites.

These workplaces may look good in pictures, but they do not chime with most people's experience of work.

Fewer than one in 10 people work in manufacturing and even fewer in construction.

The vast majority of the UK's workers are employed in service jobs

In contrast, four out of five people work in service industries.

This covers everything from bank workers to plumbers and restaurant staff - the businesses that provide work for customers, but which don't manufacture things.

These service sector jobs have grown over time: 20 years ago they made up less than three-quarters of employment.

The biggest growth since then has been in public administration, education and health.

Over the same period, the biggest fall has been in manufacturing, where the share of jobs has halved since the 1990s. The sector now provides employment for just under three million workers.

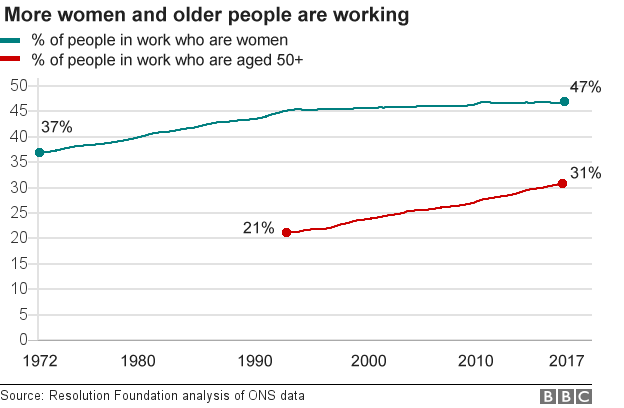

Workers are older and more likely to be female

The world of work may once have been a man's world, but that is no longer the case.

At the start of the 1970s, a little over one third of workers were women.

But rapid growth in female employment during the 1970s and 1980s means that women now make up almost half of the workforce.

However, there are still big challenges in terms of how men and women experience work, like the enduring gender pay gap - which is 18% for all workers and 9% among full-time staff.

Nonetheless, rising female employment has been one of the key drivers of improvements in living standards over the past 50 years.

More recently, the workforce has also grown older.

Nearly one in three people in work is now aged 50 and over, compared to just over one in five back in 1992.

This trend is being driven by rising life expectancy, the progress of the large baby boomer generation through their careers and policy changes like the increasing state pension age.

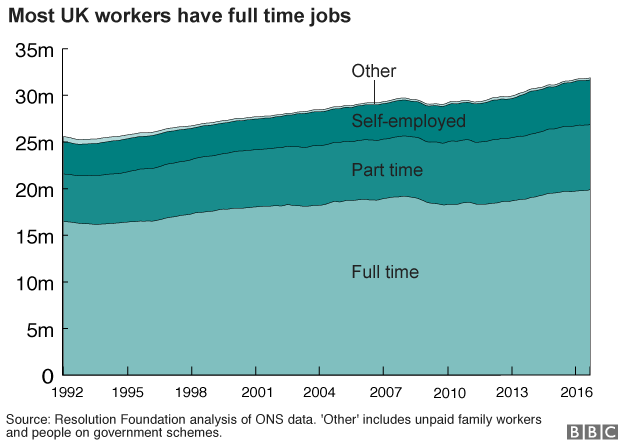

A work life less ordinary

The changing nature of work and the jobs people do to make ends meet has become an increasingly important issue.

At present, there is a particular focus on the emerging gig economy.

The term is often used to describe short-term casual work, although there is some disagreement about exactly what it means and the number of jobs it includes.

However, what is clear is that ways of working that might be thought of as atypical have increased.

In the UK there are nearly five million self-employed people, from highly-paid management consultants to delivery drivers - an increase of 50% since the turn of the millennium.

In addition, there are 900,000 workers on zero hours contracts and 800,000 agency workers. Both groups have grown markedly in recent years.

Less clear is what is driving this and whether these jobs provide an acceptable balance between flexibility and security for workers.

As a result, the government has commissioned a high-profile review of employment practices in the modern economy which will report later this year.

But a traditional full-time job is still the norm

Although the world of work is changing, it is still the case that most people have what might be called traditional jobs.

Nearly two-thirds of people in work have full-time roles for an employer - a proportion that has fallen only slightly since the early 1990s.

The average working week is 32 hours long, only an hour shorter than it was a quarter of a century ago.

Even if we only focus on workers aged under 30, it remains the case that two-thirds - more than five million of them - have full-time employee jobs. However, this proportion has fallen a bit faster since the early 1990s.

But with 32 million people in work overall and the employment rate at a record high, job numbers have never been stronger going into an election.

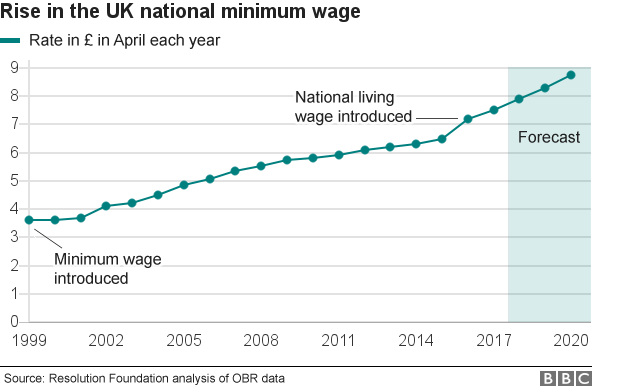

The minimum wage has helped low earners

For most people, living standards are determined by whether they have a job - and how much they get paid.

For the lowest-paid workers, the introduction of the National Minimum Wage in 1999 set a minimum hourly rate for the first time.

It has since risen faster than both inflation and average earnings.

The bar was raised further with the introduction of the National Living Wage in April 2016, bringing a 70p hourly pay rise to millions of minimum wage workers aged 25 and over.

This meant that the earnings of the lowest-paid are growing faster than average earnings - a trend which is forecast to continue.

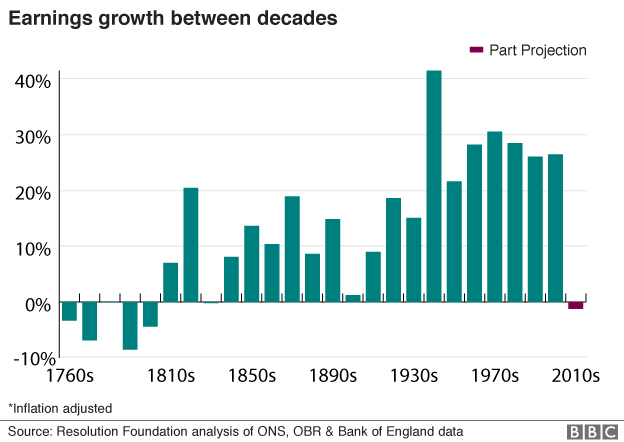

But pay rises haven't been worse since the Napoleonic wars

The wider picture for earnings is not so positive.

The UK experienced a pay squeeze following the financial crisis of 2008, with wages growing more slowly than prices for five years.

Helped by low inflation, a couple of recovery years followed, but real wages are once again falling as pay fails to keep up with inflation.

Combined with the Office for Budget Responsibility's gloomy economic forecasts for the coming years, it looks likely that average real pay will be lower in the years 2011 to 2020 than it was between 2001 and 2010.

That would make this the worst decade for earnings in over 200 years.

Average earnings are £480 per week, but they would be closer to £600 per week if these two periods of pay squeeze had been avoided.

Improving productivity is going to be key for any government if it wants to deliver for the hard-working people it champions.

Achieving that, however, will not be straightforward.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Laura Gardiner, external is a senior research and policy analyst at the Resolution Foundation, specialising in the labour market.

The Resolution Foundation, external describes itself as a think tank that works to improve the living standards of those on low to middle incomes.

- Published17 May 2017

- Published9 March 2017