Election 2017: How do people actually decide whom to vote for?

- Published

After weeks of political campaigning, the UK's electorate is about to be asked to choose a new government. But do people actually listen to politicians before deciding how to cast their vote?

The introduction of the Fixed-term Parliaments Act in 2011 was supposed to ensure that we all had five years to decide whom to vote for in a general election.

But on 19 April, Theresa May cut our thinking time short - bringing polling day forward three years and giving us just eight weeks to make up our minds.

For some of us, choosing which box to cross on the ballot paper is straightforward.

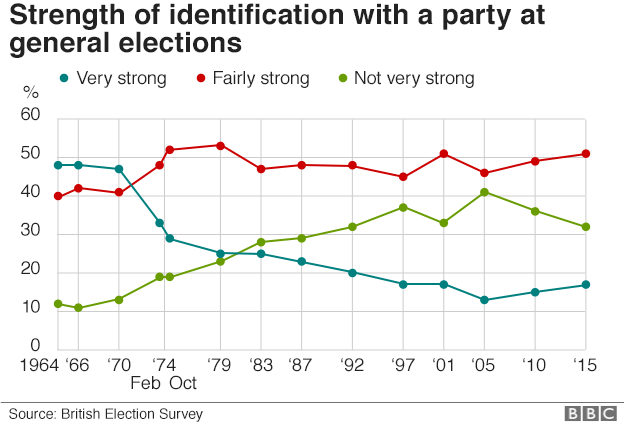

A sizeable, but shrinking, proportion of voters usually vote the same way election after election.

This deep emotional commitment used to be strongly related to social class.

In 1964, more than six out of 10 voters were either middle-class Tories or working-class Labour supporters.

But institutions such as churches, trade unions and social clubs no longer play such a central role in many people's lives and what might have been called traditional working-class jobs have declined.

Harold Wilson toasts members of a working men's club in his constituency, in 1964

Class is now a very poor predictor of how people will vote.

From the 1990s Labour ceased to get most of its support from working-class voters, external, and in April a YouGov poll suggested support for the Tories had little to do with background, external.

As a result, we have become much more individualistic in our political beliefs and are less likely to be "party people".

At the 1964 general election, about 48% of people said they identified with a party "very strongly". In 2015, this figure was 17%.

The Conservative and Labour parties still rely on loyalists to make up their core vote, but this dependable base has ebbed away.

In 1966 just 13% of voters switched parties between elections, but by the 2015 general election nearly 40% did so, external.

Status quo

Given that more of us are changing our minds, what are the main influences?

The way the media frames the election and the twists and turns of the campaign plays a part, but other factors also shape our decision.

For example, the way that we respond to the promises we hear political parties make is influenced by our own beliefs and values.

Some US studies even suggest that as much as 40% of our political values are shaped by our genes, external.

They say we are predisposed towards one of two groups:

those excited by and open to new experiences

those who are more cautious and likely to preserve the status quo

In the US, these traits are associated with liberalism and conservatism respectively - typically left and right in the UK.

There is also a significant division among British voters between those who consider themselves socially liberal - often the young, university educated and those in professional jobs - and those who express more authoritarian views.

The role that social values play was brought into sharp relief by analysis of the Brexit vote.

Some research suggests that support for "authoritarian" policies such as bringing back the death penalty is much more closely associated with being pro-Brexit than with Remain.

Damaged reputations

But although choosing the party that most closely reflects our values is important, whether or not we believe it can actually deliver on key issues might come first.

For example, voters might prioritise a strong economy or smoothly functioning NHS and judge the ability of the parties and their leaders to manage them effectively.

Famously, events shape our evaluations of parties' competence.

When Britain fell out of the Exchange Rate Mechanism, in 1992, external, the Conservative Party's reputation for sound economic management was damaged for more than a decade.

The 2008 financial crisis had a similar, if retrospective, effect on evaluations of Labour's economic competence, external.

The 2008 crash affected attitudes towards the Labour government's economic reputation

At this election, it is Brexit that will be profoundly important to many voters - and whom they consider best placed to deliver a good result for Britain will have an enormous impact.

The recent terror attacks and how voters judge the parties' responses will also play a role.

Fear and anger

Emotions can also play a critical role in all of this.

How an issue or political party leaves us feeling can be just as important as how we judge policies and the abilities of leaders.

For example, following the 2010 general election, research among Labour voters, external suggested that those who were angry about the financial crisis were considerably more likely to switch their votes than those who were fearful.

This could be because anger motivates us to remove the threat whereas fear tends to make us cautious and more likely to stick with what we know.

It is also worth remembering that while we tend to focus on the national campaign, general elections are in fact a series of 650 local contests.

In our first-past-the-post electoral system, some people will cast a tactical vote.

In 2015, for example, 7% of voters questioned by the British Election Study said they did not vote for their preferred party because they felt it had no chance of winning.

In the UK, we mostly vote on the basis of party, but the characteristics of the candidate can influence us too.

More attractive candidates have been shown to have an advantage over their less attractive rivals, external.

And in my own research I have seen that some voters place more emphasis on candidates' local connections, external than their sex, age or education.

It has even been suggested that among undecided voters the order of name on the ballot paper can be a factor, with US research suggesting the top candidate can gain up to three percentage points - enough to swing a tight race.

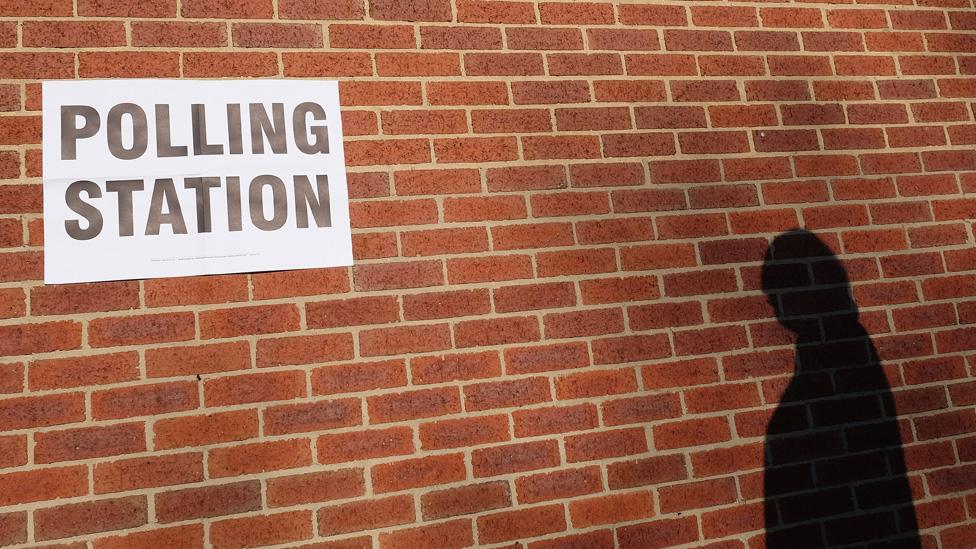

Finally, a central element of deciding how to vote is whether to turn up to the polling station at all.

Opinion polls early in this campaign that suggested an inevitable Conservative landslide could have convinced some people that their vote was irrelevant.

Some more recent polls, which suggest a tighter race, could lead more people into the polling booths.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Rosie Campbell , externalis professor of politics at Birkbeck University of London, specialising in voting behaviour, political participation, representation and gender. Follow her @ProfRosieCamp, external.