General Election 2017: Where is the Lib Dem fightback?

- Published

Tim Farron out campaigning

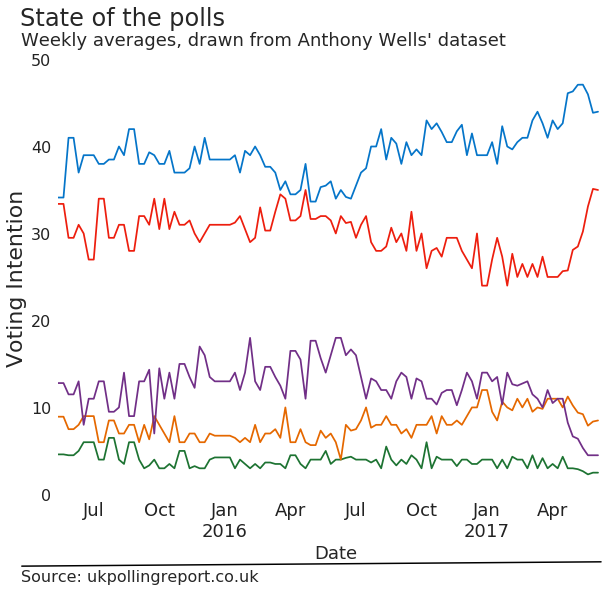

You might have thought, after the clobbering they received in 2015, that the Liberal Democrats would surely be on a steep recovery path. Why, then, has their standing not improved during this election campaign?

Why did they not do that well at the local elections? They may yet recover and do well at this election - but, so far, it has not happened. Indeed, it is possible they have gone backwards.

One must apply all the usual caveats about polls that have not been tested since the 2015 polling fiasco. At the moment, they imply the range of outcomes for the Lib Dems is anywhere between a drop from their current nine seats, to a very modest rise.

This is certainly not the Lib Dem fightback they had been hoping for. They have overtaken UKIP once again, but only because UKIP is having such a rough time.

Tim Farron, the leader, himself has been blamed for this weak performance. That may be unfair. The party's membership is buoyant, but its capacity to deploy door-knockers is much diminished. They were knocked back so hard in 2010-15 that they have dropped out of contention in some parts of the country and struggle for national media attention. Their return could never have been as swift as their descent.

You may also hear people blame the party's position on the European Union for their weak performance. It is certainly causing them trouble in what journalists must, by law, refer to as "their West Country heartlands". But the European question is one of the things that bind Lib Dems together. Could the Lib Dems have been anything other than the most pro-EU party in the country?

Perhaps they could have finessed their position a bit harder - maybe making themselves the "single market" party or setting tests for any Brexit deal.

I have also heard a few complaints about the campaign's focus on Brexit. Perhaps they are not playing their hand well, but the Lib Dems could never be as comfortable with leaving the EU as Labour or the Tories - and this puts them in a bind.

A Lib Dem aide joked to me about this election being their Kobayashi Maru, external - a reference to a training scenario in Star Trek, where captains are faced with a no-win situation.

Britain is simply not in the midst of a liberal moment. It has turned against EU membership and lots of anti-Tory voters have not forgiven them for joining the coalition.

Indeed, the truly pessimistic case for Lib Dems is to see the poll ratings of recent decades as an aberration, not the norm to which we return. For much of the 20th Century, they were a little party. Jo Grimond led the party from six MPs in 1956 to 12 by 1966.

Jo Grimond, former Liberal leader, pictured in 1979

A liberal future?

Is there, though, a case for Lib Dem optimism in the longer term?

I think the bullish case for the Lib Dems goes something like this. Currently, they have a convoluted position - in favour of a negotiation on withdrawal before refighting the EU referendum.

Forget the fine print: the point of it is to signal that they are steadfast Remainers. And it is possible that, by the next general election, that might pay off.

The Brexit negotiations are not going to fulfil some of the hopes that have been invested in them. And, if things do go wrong with the talks, the Lib Dems may enjoy a rise in support from Remainers who are currently resigned to pressing ahead with Brexit.

Some experienced leading lights - Sir Vince Cable, Sir Ed Davey and Jo Swinson - may also return to parliament at this election.

That is a very precarious and uncertain path back to relevance. It is a tough grind for little parties to make themselves heard. And even if things go badly with Brexit, a lot of effort will have been sunk into it by the time we next vote on the topic. Even former Remainers may think we should persevere with the project.

Reasonable people can differ on how the Lib Dems should respond to those risks and opportunities. Parties, even very old ones, have no right to exist. They may need to bend an uncomfortable amount on Europe in the coming years.

Conversely, parties must have a soul. Or, like ice cream vans on a beach, external, they all end up parked together.

Perhaps the Lib Dems are better equipped to face a spell in the wilderness than others, though. They have always prized their presence in local government more than the other parties - and people do not generally join the Lib Dems because they are seeking a fast track to ministerial office.