Facebook becomes key tool in parties' political message

- Published

Much of parties' budgets is now being spent on targeted digital advertising

Political parties are suddenly spending much more money on targeted digital advertising on Facebook. Are they profiling users and tailoring messages specially for them?

Something pops up in your Facebook feed. It says that Jeremy Corbyn is a threat to national security. Or that Theresa May is too scared to debate.

And yet the same advert isn't in your friend's feed. So how did they know to target you?

During the 2015 election, the UK's political parties spent about £1.6m on ads and other media that ran online. The majority of that cash, external, £1.3m, was paid to Facebook. The Conservatives accounted for £1.2m of that spend.

The focus on Facebook increased during the Brexit referendum. Dominic Cummings, director of the Vote Leave campaign, said it put 98% of its cash into digital adverts. Over the course of 10 weeks it served about one billion targeted ads - most of which were despatched via Facebook.

Mr Cummings said the campaign went through a well-managed process of refining the adverts to make sure they reached the right people at the right moments.

"Many big-shot traditional advertising characters told us we were making a huge error," Mr Cummings has said of that campaign. "They were wrong. It is one of the reasons we won."

Both parties now have units dedicated to using social media to get at voters.

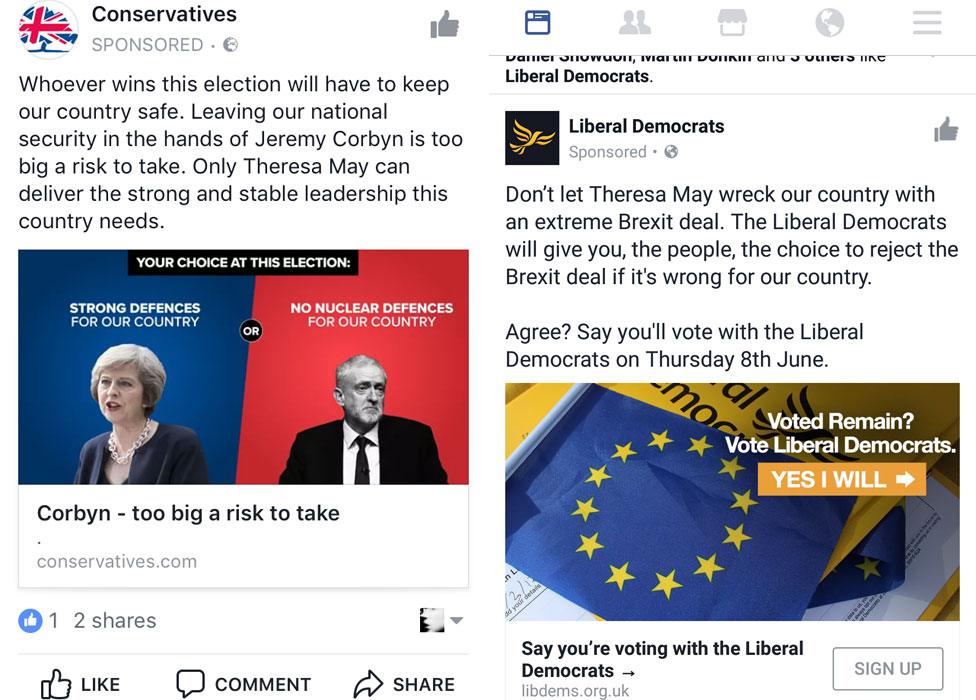

Screenshots from users of Conservative and Lib Dem adverts

Facebook survives on its ability to match advertisers with potential customers, says Frederike Kaltheuner, a researcher at the Privacy International digital rights group who has studied the profiling systems of Facebook and other social-media platforms.

Facebook believes it can do this with unprecedented accuracy because of what people share on the social network. That data helps advertisers get deep insights into the likes and dislikes of huge numbers of Britons - more than 90% of the UK's social-media users have a Facebook account, according to the Office for National Statistics.

Activists have begun to try to monitor political advertising on Facebook. Volunteers run the Who Targets Me? project. This is logging ads turning up in news feeds via a software add-on for the Chrome web browser.

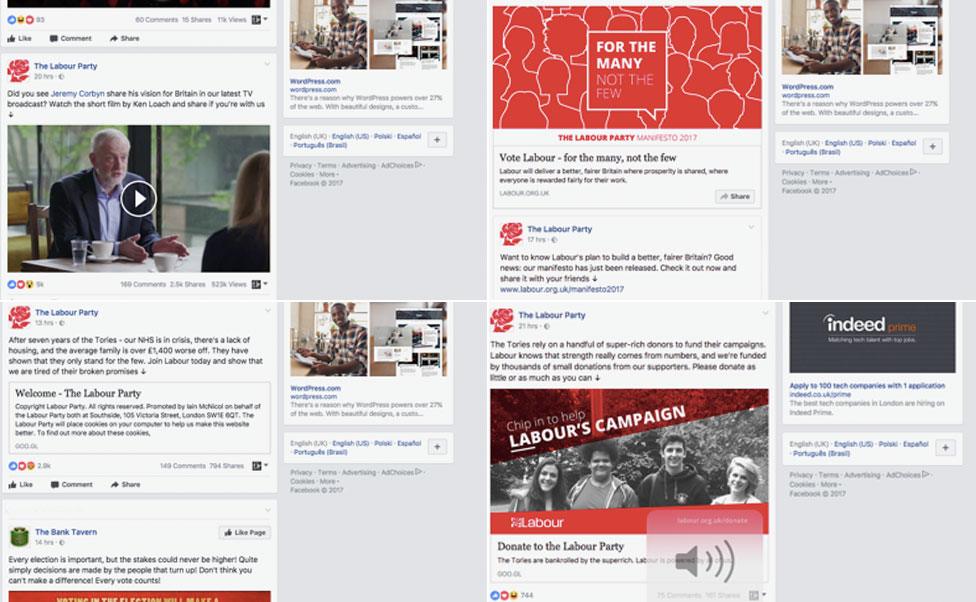

Labour and the Conservatives are expected to spend about £1m each on Facebook ads in 2017, says Sam Jeffers, one of the co-founders of Who Targets Me. The project plans to grab copies of as many adverts as possible to create an archive, to monitor the differing claims and to see how parties target people. It has volunteers in more than 95% of the UK's constituencies.

Early analysis by the project has unveiled the different tactics used by the parties. The Conservative ads tend to focus on Jeremy Corbyn but by contrast only two out of the 14 Labour ads caught by Who Targets Me? feature the party leader. That is a small fraction of all the adverts it has prepared, external as it recently said it was running about 1,200 different adverts via Facebook.

That early work has also revealed how flexible the social-media-based ad campaigns can be. Within hours of the Conservative Party being criticised for its proposed changes to social care, ads starting popping up, external trying to set the record straight about what had been dubbed the "dementia tax".

Adverts are only the most visible part of the parties' efforts, says Ms Kaltheuner. She is worried by the work being done by data-science firms to build up a psychological profile of Facebook users.

"Profiling is about making inferences about a person's interests, behaviour and personality just from data," she said.

The uncanny accuracy of these inferences was revealed in a study of 58,000 Facebook users published in 2013. Just by studying what people "like" it was possible to infer race, age, IQ, sexuality, substance use, political views and personality - even though subjects had not answered any questions about how they felt about those topics or whether they shared a particular trait or lifestyle.

It also enabled academics at the University of Cambridge Psychometrics Centre to predict whether someone was gay (88% accuracy), African American (95%) Republican or Democrat (85%) or even whether a subject's parents separated before they were 21 (60%).

"Likes", too, were also indicative of broad personality traits, such as intelligence, emotional stability, openness and extroversion. In some cases, it found the "likes" were just as accurate as a standard personality test.

Screenshots taken by a Facebook user who supports Labour

Many of the staff who worked at the Psychometrics Centre on that ground-breaking study have reportedly been snapped up by Cambridge Analytica. The company, and many others, have taken the early work and extended it to make it more detailed.

Now they tend to look at five broad personality traits - openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness and neuroticism.

"What's changed is the way in which this has become much more fine-grained and invasive," said Ms Kaltheuner.

Profiling firms make all kinds of claims about what they can do with this information. Some claim that it gives them levers that, if pressed at the right time, can move people's beliefs and voting intentions.

Wild West

That clearly is a great concern for some experts.

"We're currently in a Wild West of experimentation in political data science," says Prof Damian Tambini, an expert on media, communications and politics at the London School of Economics. "Social media is a completely unregulated space."

But he believes more work needs to be done to see whether the claims made by the profiling and analytics firms are actually borne out. "What we need to find out is how much snake oil is there in their so-called secret sauce."

At the very least, he says, the Electoral Commission needs to tighten up its rules governing campaign spending to take into account cash spent on data science. "A lot of the costs which matter are in designing the tools and creating and cleaning the database that allows the targeting to happen. That's a sunk cost that takes place outside the election reporting period."

The use of voter data has now attracted the attention of Elizabeth Denham, the UK's Information Commissioner (ICO). In mid-May she announced the ICO was looking into the political use of private data.

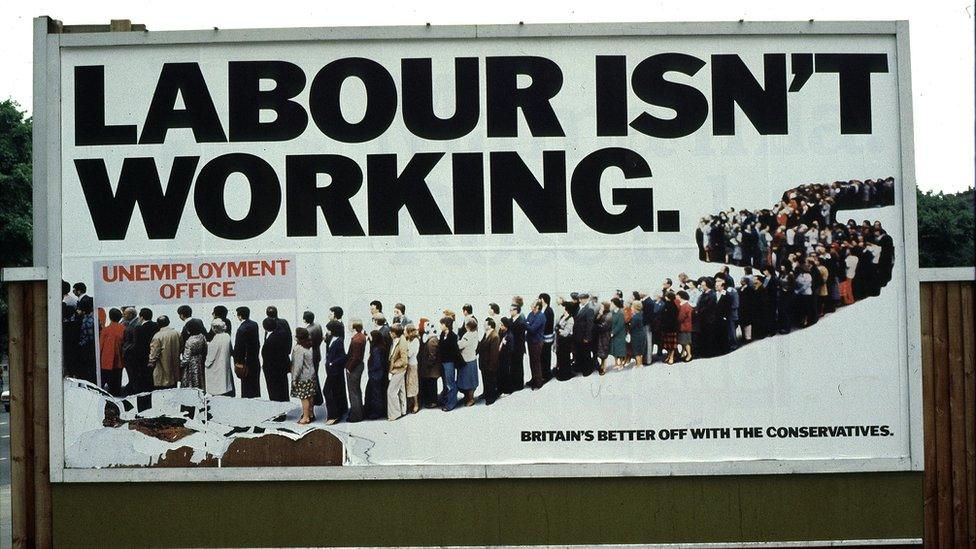

Arguably the most famous British political advert was a billboard

"What is clear is that these tools have a significant potential impact on individuals' privacy," said Ms Denham in a statement announcing the review.

The commission is also looking into the money spent by the Leave.Eu campaign on data analytics.

For Ms Kaltheuner there are a number of potential problems with Facebook profiling in particular. It is often not very accurate, largely because it is based on inferring someone's personality from only a very narrow view of their behaviour. And there's a question of fairness.

"When you sign up for Facebook you sign up for a lot of things but what you have not signed up for is them using your feelings or state of mind.

"It is used to manipulate people? This is not even a question," says Ms Kaltheuner.

Skirting the rules

One sign of the importance of political advertising to Facebook is that the social network now reportedly has staff, external helping the main parties target adverts and users

There are fears that the virtual politicking lets parties skirt strict rules on what they can say and on how much they can spend when campaigning in elections.

"The rules were designed for the old world of newspapers, hoardings and leaflets," says Prof Tambini.

These rules try to ensure that voters know who is sending them campaigning material, he said. Keeping an eye on the claims and counter-claims is easier as physical copies aid the Electoral Commission's efforts to hold parties accountable if they lie, exaggerate or overspend.

"That transparency is all about giving the public the tools they need to inform themselves," said Prof Tambini. "Doing that fully online is very difficult."