Reality Check: Can we be self-sufficient in renewable energy?

- Published

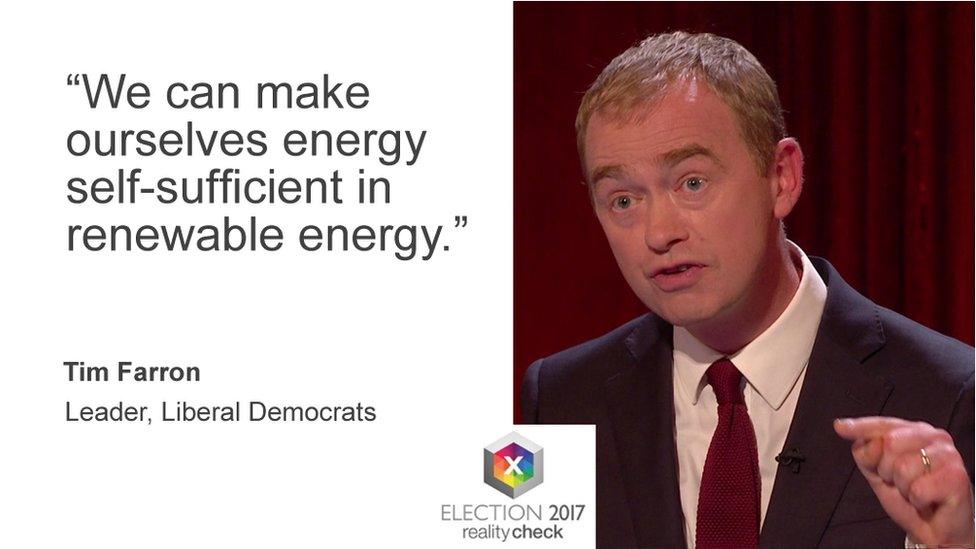

The claim: The UK can make itself energy self-sufficient in renewables.

Reality Check verdict: This is not the policy in the Liberal Democrat manifesto, which pledges to get 60% of electricity from renewables by 2030. Being self-sufficient and having all energy coming from renewables would require considerable development of storage technology to avoid having to use non-renewable sources or energy bought from overseas as back-up sources.

In Wednesday night's debate, Liberal Democrat leader Tim Farron said that the UK could become energy self-sufficient in renewable energy.

It came after he had said: "If it is simply for hair shirt, muesli-eating, Guardian readers to solve climate change... we're all stuffed."

Becoming energy self-sufficient in renewables is not current Liberal Democrat policy, although Mr Farron described it in a speech in February, external as being a "patriotic endeavour".

The manifesto, external says the party would: "Expand renewable energy, aiming to generate 60% of electricity from renewables by 2030."

A party spokeswoman described the leader's statement in the debate as "visionary as opposed to completely literal".

The problem with being entirely self-sufficient is that many renewable sources of energy cannot generate power all of the time (the notable exception being the burning of biomass), so if you are using a very high proportion of renewables you rely on interconnectedness (buying electricity from another country where the wind is blowing), storage (batteries in the short-term, some sort of gas storage in the longer term) or a back-up system using gas-fired power stations or nuclear energy.

The Liberal Democrat manifesto talks about investing in interconnectors, which would be unnecessary if the country was to become self-sufficient.

There are already private plans in place to increase the amount of electricity that may be bought from France via interconnectors.

It may be that when he said self-sufficient he meant that we should not have a trade deficit in energy, so it would be OK to buy energy from other countries when we needed it as long as we sold the same amount to other countries when they needed it.

While there have been suggestions that, external marine energy could make the UK a net exporter of electricity, being self-sufficient and generating 100% of energy from renewables is considerably more challenging than, for example, 90%, mainly because of the challenges of storage.

The development of a smart grid, which co-ordinates renewable energy supplies depending on demand, may also be needed for a 100% renewable system.

Also, while the Liberal Democrat manifesto targets 60% of electricity, Mr Farron was talking about all energy, which means, for example, that all cars have to run on renewable energy and all buildings have to be heated by it.

So in 2016, the UK generated 24.4% of its electricity from renewables, external, but in 2015 (the latest year available) it was only producing 8.8% of energy from renewables, external.

The UK has an obligation under European Union rules to derive 30% of electricity from renewables by 2020, external, which it is on the way to achieving (although the UK is currently scheduled to have left the EU by then). But the other two parts of the targets are 12% of heat and 10% of transport to be powered by renewables, which we are less likely to achieve.

The Labour manifesto, external pledges to get 60% of energy from zero-carbon or renewable sources by 2030.

The Conservative manifesto, external looks at it in a different way, saying that "energy policy should be focused on outcomes rather than the means by which we reach our objectives".

So they say that the focus will not be on how the energy is generated but on achieving, "reliable and affordable energy, seizing the industrial opportunity that new technology presents and meeting our global commitments on climate change".

The Green Party would have a target of near-100% renewable electricity generation by 2030 with significant investment in electric vehicles and lower-carbon sources of heating.

It supports self-sufficiency and a decentralised system of communities owning their own generation systems, but would also invest in interconnectors to allow for co-operation with other countries.

- Published1 June 2017

- Published31 May 2017