UK election: Six key lessons from a surprise result

- Published

Rather than producing a "strong and stable" government, Theresa May's election gamble has created uncertainty. So, what can we learn?

There was a Brexit effect - but not the one Theresa May wanted

Areas where most people voted Remain swung very differently from those where most voted Leave.

On the one hand, the Conservatives often secured a swing to themselves in constituencies where the Leave vote was highest.

These were nearly all places where UKIP performed best in 2015 - and so were the areas where there were most UKIP votes for the Conservatives to snatch away.

Leave seats with clear swings to the Conservatives included Boston and Skegness where there was a 6% swing to the Conservatives and Bolsover where there was as much as an 8% swing.

But seats which voted Remain last year - and where there were relatively few UKIP voters in 2015 - saw Labour pull off some of its best performances.

Just one example in London was Hampstead and Kilburn, where there was a 12% swing to Labour, while in Hove on the south coast, there was a remarkable 15% swing to the party.

It seems to be the case that Mrs May's brand of Brexit may have helped to squeeze the UKIP vote, but that at the same time it put off some Remain voters.

As a result of these patterns, while, at just under 44%, the Conservative Party secured its highest share of the vote since Mrs Thatcher's first election victory in 1979, it was not enough for an overall majority.

This was because, at 41%, Labour's vote also rose to its highest level since Tony Blair's first victory in 1997.

A question of class

One consequence of this divergent pattern between Remain and Leave areas is that there has been a marked change in the social geography of the Conservative vote.

Traditionally, the party holds most appeal for middle class voters.

But Leave voters were disproportionately working class.

Consequently, at this election the Conservative vote increased least in middle class seats, rising only two points in the constituencies with the highest proportion of middle class voters.

In contrast, the party's vote rose by no fewer than nine points in seats with the highest proportion of working class voters.

Brexit has therefore served to undermine one of the traditional features of the geography of voting in Britain.

Jeremy Corbyn won over young voters

Labour has seemingly been highly successful in getting young voters and other former abstainers to turn out and vote - and for them - just as Jeremy Corbyn intended.

Where young voters were more numerous, the swing to Labour was often especially high - places like Bristol West (16% to Labour), Cardiff Central and Canterbury (both 9% to Labour).

More generally, in England and Wales there was only a 2.5% swing to Labour in seats where fewer than 7% of the population is aged 18-24, but a swing of 5% in seats where at least one in 10 people is of that age.

Meanwhile, turnout increased most in constituencies where Labour was strongest last time, and, at the same time, its vote increased most where the turnout went up by the highest amount.

But although Labour will be delighted at having denied the Conservatives an overall majority, its own success should not be exaggerated.

Its tally of 262 seats is only a handful higher than the total that the party won in 2010, when Gordon Brown's administration was ejected from office.

Labour is still a long way away from winning a majority for itself.

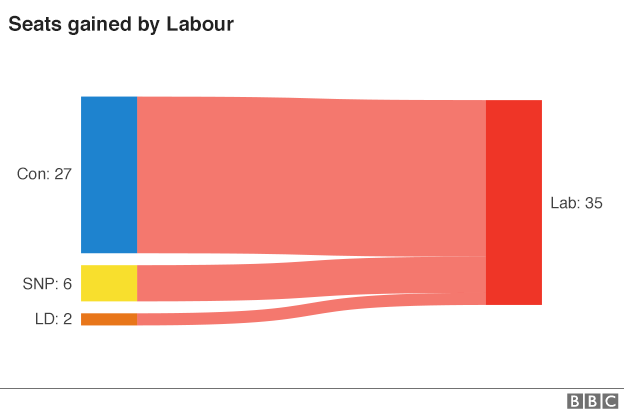

SNP snipped back

Although the SNP is still the largest party in Scotland, it lost more than a third of its Westminster seats - falling back to 35 seats overall.

This will be a severe blow to the party's morale as it supposedly tries to embark on a second independence referendum.

The party suffered the misfortune of finding that its vote fell most where the party was previously strongest, such as the 21 point drop from 60% in 2015 to 39% now in Bannff and Buchan, enabling the Conservatives to win the seat.

Key losses included its former leader Alex Salmond and its current deputy leader Angus Robertson.

Liberal Democrats' mixed bag

It was a mixed night for Tim Farron's party - gaining eight seats but losing four.

The party has on average seen a small increase in its support in constituencies with the largest number of those with degrees, most notably in London.

But otherwise it has typically fallen back.

Tim Farron's party had a mixed night

However there have been a number of notable personal performances such as gains in Bath, Eastbourne and Twickenham.

The damage that the party suffered from its involvement in the coalition in the 2010-15 parliament has not begun to be repaired.

Almost everybody lost

This is a result that brought disappointment to all parties.

The Conservatives lost their majority.

Labour suffered its third defeat in a row.

The Liberal Democrats found themselves treading water.

The SNP's independence bandwagon came to a juddering halt.

And UKIP imploded.

It is not only Conservatives who will be asking why Mrs May changed her mind about holding a snap election.

The only winners are perhaps the DUP - to whom she seems to have awarded the role of kingmakers.

Sorry, your browser cannot display this content.

- Published9 June 2017

- Published7 June 2017

- Published9 June 2017