General election 2019: Labour gambles on 'radical' strategy

- Published

Jeremy Corbyn: "Whose side are you on?"

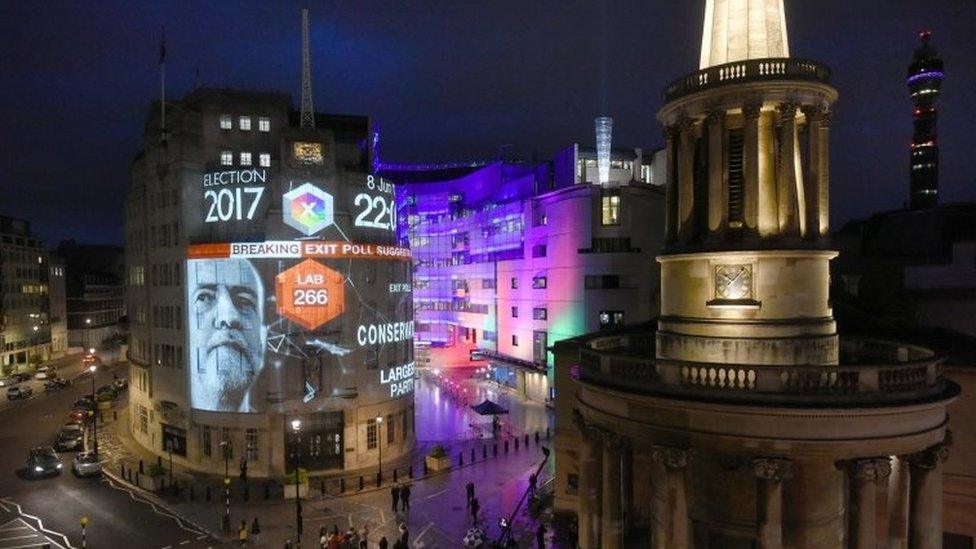

At first glance, Labour's campaign launch appeared like a replay of its 2017 election launch.

Back then, Jeremy Corbyn attacked vested interests - and pledged that his party would be battling for the many not the few.

Businessman Mike Ashley has had the honour - if that's the word - of featuring in Labour's rogues' gallery of "bad bosses" in both the 2017 general election campaign launch and again today.

But the tone, if anything, is more strident now.

Channelling the left-wing folk singer Pete Seeger, the Labour leader repeatedly - and rhetorically - asked his audience whose side they were on.

He made it clear his party was against "dodgy landlords", big polluters, tax dodgers, rich media magnates.

It looks like this will be something of an insurrectionary campaign.

Partly, this is to inoculate the party against the Conservative charge that it is siding with the political class against the people on Brexit - causing "dither and delay".

So Jeremy Corbyn is trying to get his retaliation in first - by arguing it is Boris Johnson and Tories' financial backers who are really part of a privileged elite.

But Labour's tone is a form of attack as well as defence.

Beyond Brexit

As in 2017, Labour is aiming to win over younger voters and those who rarely vote - and who need to be convinced that politics can make a difference.

Hence the clear blue - or red - water between Labour and their opponents.

Labour is hoping to focus voters' minds on non-Brexit issues

And it's part of a wider strategy to try to appeal to potential Labour voters beyond the Brexit debate.

Jeremy Corbyn for some time has argued that while working class voters may be divided on the EU, they can be united in support of better working conditions, fairer taxes, and more investment in public services.

The strategy is to try almost to divorce Brexit from the other issues, arguing that can be settled further down the line in a referendum with a "credible" Leave option and Remain on the ballot.

In Leave areas - where Labour is seriously worried about suffering losses - the hope is that however much the party's voters or ex-voters want Brexit done, they will prioritise other issues directly affecting their lives.

Wider agenda

So, Labour strategists believe it is essential on the wider non Brexit agenda to have as distinctive a message as possible.

Now, some Labour MPs argue that - with circumstances rather different now than in 2017 - Labour could have played this election differently.

With an exodus of former Remainers from the Conservative ranks, technically the party could have blurred its more radical edge - don't forget, in 2017, the leadership claimed their manifesto's policies were in the tradition of mainstream European social democracy - and made a pitch for the centre ground,

But that is unlikely to have passed the authenticity test with Jeremy Corbyn at the helm.

Labour did better than many expected in 2017

And some in Labour's ranks have been saying privately that the uncompromising messaging and the forthcoming radical manifesto are designed to shore up, rather than greatly expand, the Labour contingent in Parliament.

After all, the campaign launch was in Battersea - a marginal they hope to hold, rather than a seat they aspire to win.

Policies that will motivate the party's foot soldiers will help in the defence of some seats won by very slim majorities last time round.

And there are sophisticated methods being deployed by the left-wing group Momentum to move activists around to where they are most needed.

The winning post

There are, of course, different measures of what winning looks like.

For Boris Johnson an overall majority is essential.

If Labour, though, can become not outright winners but the largest party in a hung Parliament, it could very likely form a minority government with tacit support from the SNP and, possibly, the Liberal Democrats in order to deliver a new EU referendum.

But, of course, Jeremy Corbyn insists he is fighting to win and that most opinion polls are probably as misleading now as they were two and a half years ago.

And that even more now than then, middle as well as working-class voters do not feel, in their day-to-day lives, that austerity is over - whatever spending pledges are being made by the prime minister.

So the potential reservoir of support could be greater than the current state of the polls suggest.

But some challenges lie ahead for Labour - including how far the Brexit issue really can be contained within a "cordon sanitaire".

And there remains a question - whatever the rhetoric - about just how radical Labour will be.

Will a conference policy on abolishing private schools, and another on extending the free movement, really make it in to the manifesto?

This is an election many Labour MPs didn't appear to want, with widespread abstentions in Tuesday evening's vote.

But some of those closest to Jeremy Corbyn were champing at the bit for an election.

They believe if Labour are currently being seen as also-rans, opponents will become complacent and in the end - however radical the party's message - progressive centre-left voters will be forced to back them if they want to stop Boris Johnson.

In this election, though, there is no such thing as a sure thing.