General election 2019: Did a bunch of bananas lead to Brexit?

- Published

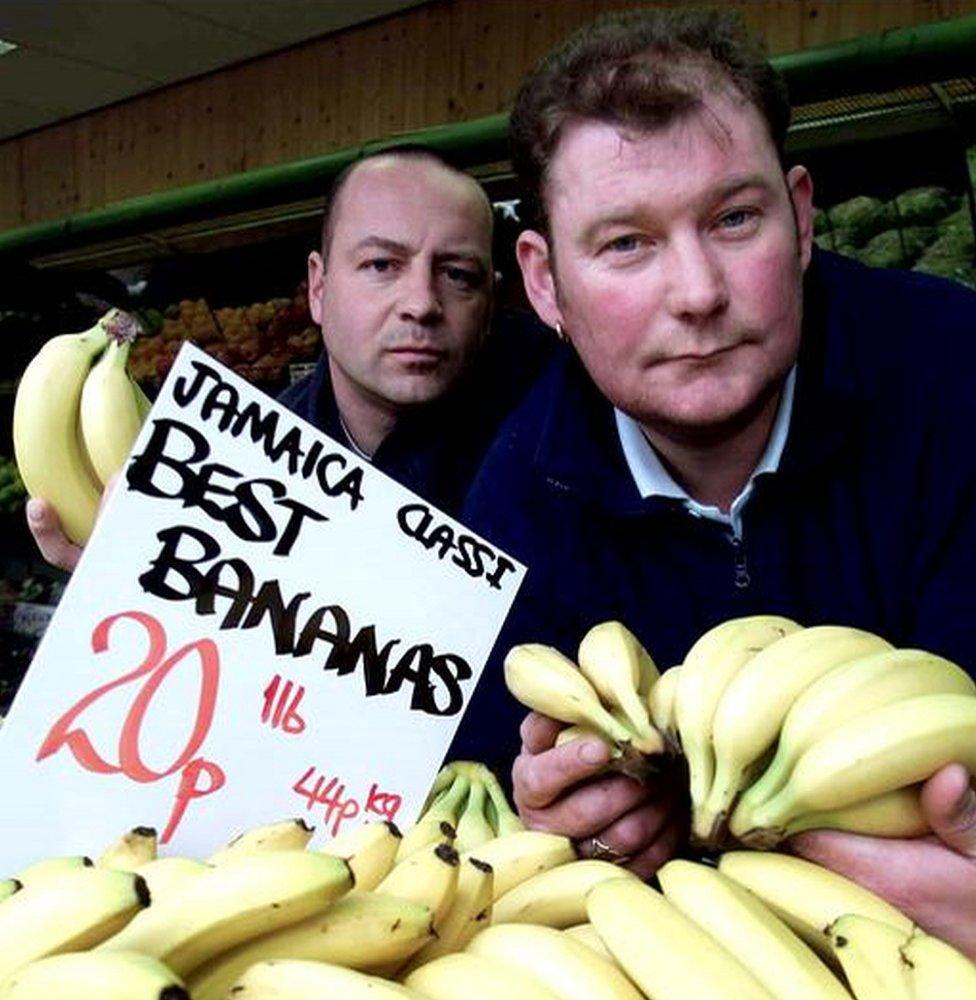

Sunderland greengrocer Steven Thoburn became a celebrity as one of the so-called "metric martyrs"

Did a bunch of bananas help change the course of history and shake the foundations of British politics?

It's a bold claim which, on the face of it, seems absurd. But let me take you back to the early hours of 24 June, 2016.

I'm in the Silksworth Sports Centre in Sunderland. The city's result in the European Union (EU) referendum has been declared and it is the first place in the country to return a leave vote.

The scenes of a woman in a red Vote Leave T-shirt being hoisted on the shoulders of other leave supporters are being flashed around the world and, for many, Sunderland is now indelibly associated with the UK's decision to exit the EU.

Photos of the woman in the Vote Leave T-shirt celebrating the first referendum result went global

As results from the rest of the country come in I fall into conversation with Colin Moran.

His name may not be familiar but, in the early part of this century, he was part of a campaign that he argues helped turn public opinion against EU membership, giving critics something tangible to point to that affected people's everyday lives and for which Brussels appeared responsible.

Mr Moran was one of the prime movers behind the Sunderland "metric martyr" campaign which began in 2000 when police and trading standards officers arrived at the market stall of trader Steven Thoburn.

Mr Thoburn had sold a bunch of bananas for 34p to an undercover trading standards officer using pounds and ounces. His scales were confiscated and, the following year, he was convicted of breaking a law that had originated as a directive from the EU, requiring the use of metric units.

Mr Thoburn became a celebrity. His case attracted national and international attention and high profile support. The judge described the fruit in question as "the most famous bunch of bananas in English legal history".

Was this the moment anti-EU sentiment found an outlet, beginning a Eurosceptic journey leading to the leave vote of 2016?

Mr Moran certainly thought so in 2016. To him, then, the leave vote came as no surprise, especially not in Sunderland.

These days he still has "no doubt at all" the resulting "metric martyr" campaign gave the British public a focus. "Everybody could see how wrong and unjust it was and began asking themselves the question, 'who are these people we're electing and agreeing all these things in Brussels?'"

Steven Thoburn (right) and fellow campaigner Neil Herron lost their High Court battle for the legal right to trade in pounds and ounces

As we approach the general election, Brexit - and that bunch of bananas - is having an effect, shifting electoral loyalties once defined by class and party.

The Brexit Party - now led by Nigel Farage who backed the "metric martyrs" campaign all those years ago - is standing in all three of Sunderland's seats. And its candidate in the Houghton and Sunderland South constituency, Kevin Yuill, believes Brexit has shaken up old political allegiances in a city that has voted Labour for decades.

"I can't count the number of people who have said 'I will never vote Labour again'," he says. "Most people who are saying they'll never vote Labour have voted Labour for generations. So I think a lot of people cannot bring themselves to vote Tory, but they will bring themselves to vote Brexit Party."

But UKIP still views itself as the original party of Brexit and is standing candidates in two of the three Sunderland constituencies. Houghton and Sunderland South candidate Richard Elvin dismisses both Brexit Party and Labour rivals.

"Labour do not represent the true working class people as arguably they did in earlier times," he says. "After this election, the Brexit Party will be a busted flush. You see how many Brexit [Party] candidates you get standing in Sunderland in the May elections."

If old allegiances are shifting in Sunderland because of Brexit then, in theory, it should be fertile territory for the Conservatives, who are promising at every opportunity to "get Brexit done".

But, for some in a city where the legacies of shipyard and coal mine closures under Margaret Thatcher are still strong, the Tories have been toxic for decades.

Is it time to stop talking about the 1936 Jarrow march?

That view of the party is outdated - and muddle headed - argues Robert Oliver, who leads the Conservative opposition group on the Labour-run city council.

"It's a bit lazy of the Labour Party to talk about Margaret Thatcher and the Jarrow March and the shipyards and the coal mines when that was a long time ago and the Labour Party has controlled the North East for so long," he says.

"I think the message has to be that a vote for anyone else will simply let Labour in. A vote for the Brexit Party is going to dilute the vote."

Brexit's been a tricky issue for Labour in Sunderland. In May's local elections the party lost ground to the Liberal Democrats, Conservatives, the Green Party and UKIP.

Local issues were, of course, a factor. But, at the time, city council Labour leader Graeme Miller accused the three Labour MPs - who all support another referendum - of being out of touch with many of their voters.

One of them, Bridget Phillipson, is now the Labour candidate for Houghton and Sunderland South. She believes Brexit is not the defining issue of this election.

"In Sunderland the majority of Labour voters had voted to remain back in 2016," she says. "Even voters who voted leave are really very worried about the state of the NHS. They're concerned about what Boris Johnson will do, they're concerned about a trade deal with the US.

"This comes through loud and clear and that is causing people to reflect on how they're going to vote."

CONFUSED? Our simple election guide, external

POLICY GUIDE: Who should I vote for?, external

REGISTER: What you need to do to vote

CANDIDATES: Who is standing in your constituency?

Some, such as Green Party candidate for Sunderland Central Rachel Featherstone, fear framing the election as being about Brexit risks squeezing out other important issues.

Climate change and the environment are not being discussed but matter just as much, if not more, than Brexit, she says.

"This election just can't solve Brexit, it's not going to give us an answer," she says. "We'd like it to be the climate election."

Nissan has warned a no-deal Brexit could make its European business model unsustainable

Perhaps surprisingly for a place so strongly associated with Brexit and the leave vote, Sunderland has a strong contingent of remain voters too.

Many of them think Brexit is quite simply a disaster, particularly for a city that's home to the giant Nissan factory, which employs 7,000 people directly and supports a further 20,000 jobs in the supply chain.

Liberal Democrat candidate for Sunderland Central Niall Hodson says his party has been "unequivocal and unapologetic about being a remain party".

"That has made it quite straightforward for Labour members who are uncertain about their position on Brexit to come over to us," he says.

Before May 2016 the Liberal Democrats had no councillors in the city. Now they have eight, including one elected in a ward estimated to have returned one of the strongest leave votes in the EU referendum.

Once the election is over, some may be hoping for a return to politics as usual.

But others hope that Brexit, and that famous bunch of bananas, mean things will never be the same again.