General election 2019: What difference could tactical voting make?

- Published

The issue of tactical voting is looming large in discussions about how the 2019 general election will play out.

Tactical voting happens when a voter abandons the party or candidate they prefer, and votes for one with a better chance of winning locally - often, but not always, in order to defeat a disliked candidate.

Relatively small changes in the number of votes a candidate receives have the potential to make a big difference.

At the 2017 election 174 MPs were elected with less than half the vote, and in 2015 it was 334 out of 650. In those constituencies, supporters of the parties that came third place or lower, could have defeated the MP by backing the second-placed party.

How many people vote tactically?

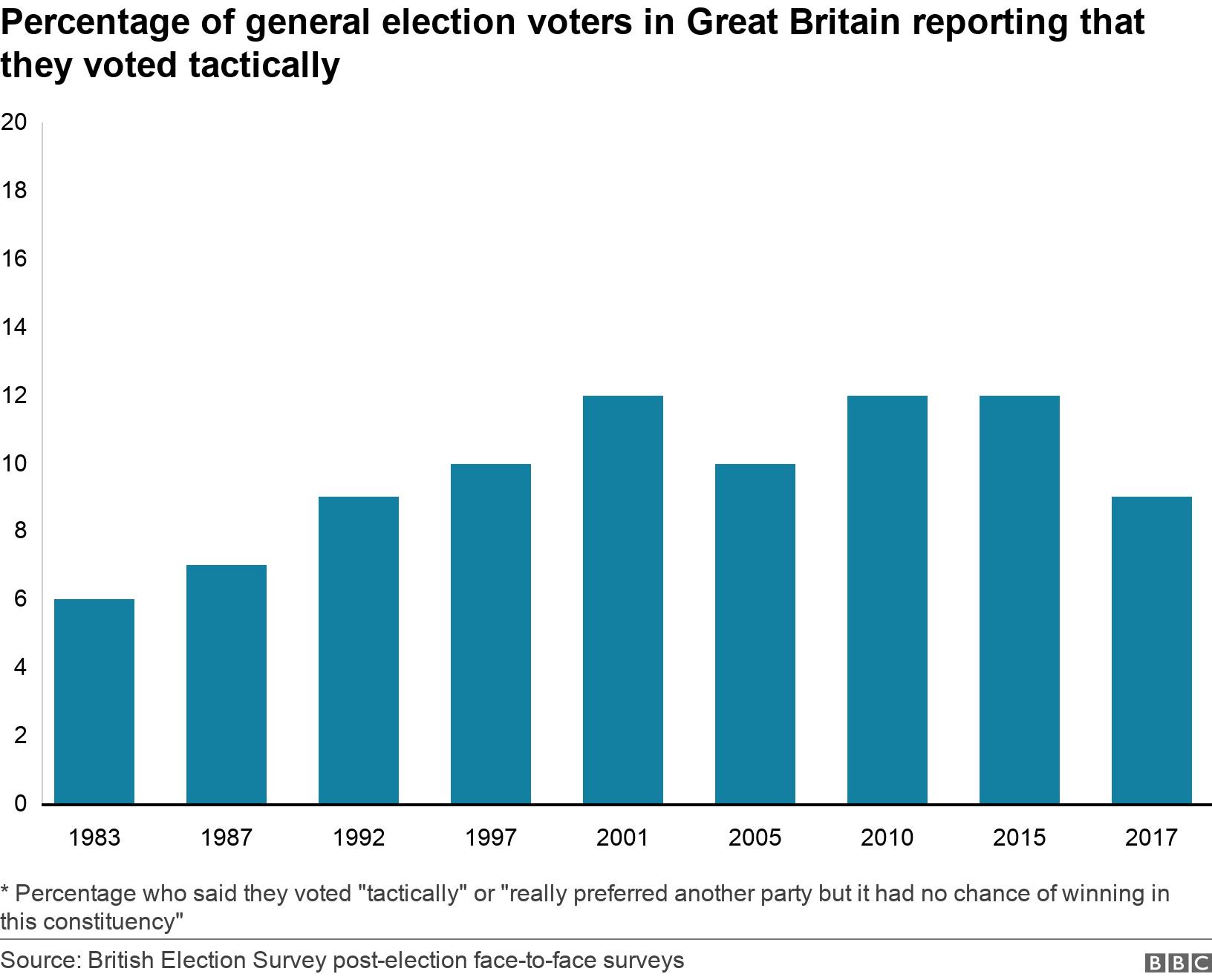

Surveys after recent elections saw about one in 10 voters - around 3 million people - saying they voted tactically.

The number of people voting tactically has not changed very much since the 1990s, despite the fact that people switch votes between elections more frequently, external.

It seems that tactical voting is not driven by political sophistication or general willingness to consider switching, so much as how much support there is for lower-placed candidates in constituencies, and how much supporters of those lower-placed candidates like their second-choice party and dislike one of the top contenders.

Tactical voting is not particularly more likely to happen in closely fought constituencies, where a relatively small number of voters can make more of a difference. People often vote tactically in relatively safe seats too.

Since it is not always clear what order the parties are going to come in, some voters make mistakes and vote tactically the wrong way - that is, for a party that ends up doing worse than the voter's preferred party.

Typically though, people are more likely to vote tactically the clearer it is that their preferred party is out of contention.

When has tactical voting worked in the past?

In the 1990s, after the Conservatives had been in power for over a decade, Labour and Liberal Democrat supporters were often willing to vote tactically for each other depending on who was best placed to defeat the Conservatives locally.

This reached a high point in 1997, external when tactical voting was estimated to have cost the Conservatives around 46 seats, with Labour taking 35 and the Liberal Democrats 11 of them.

Tactical voting played a part in Tony Blair's 1997 election victory

However, if tactical voting fails to happen in large enough numbers, it doesn't make a difference.

At the 2015 election, shortly after the Scottish independence referendum, there was an attempt to co-ordinate anti-nationalist tactical voting, external among opponents of the Scottish National Party (SNP). It even involved Conservative supporters voting Labour.

It almost certainly saved Labour from a total wipe-out in Scotland, securing their one remaining seat north of the border that year. But it was not enough to stop the SNP from winning nearly all the seats (56 out of 59) with just less than half the overall vote in Scotland.

How could tactical voting work at this election?

Tactical voting in the 2019 general election is likely to be shaped mainly by divisions over Brexit, even more so than it was in 2017.

Among Leave supporters, tactical voting is likely to come into play in constituencies where the Brexit Party and the Conservatives are competing to take a seat from a party that is sympathetic to another referendum (the Brexit Party has already stood down its candidates in seats that the Conservatives won last time).

The Conservatives' message - "get Brexit done" - is aimed partly at encouraging Brexit Party supporters to use their vote tactically in seats where the Conservatives have a better chance of winning (that is, most, if not all, of them).

Tactical voting among Remain supporters is much more complicated because it involves more parties, with varying Brexit policies.

The Lib Dems the SNP, Plaid Cymru and the Green Party are all pro-Remain. The Labour Party is in favour of a referendum but has not committed to supporting Remain or Leave.

Pro-Remain parties also disagree on other issues, and they do not always say nice things about each other's party leaders. For all of these reasons, many supporters of these parties are not keen on switching tactically in favour of one of the others.

It is often difficult to identify Remain candidates best placed to win seats from Conservatives. This is because different pro-Remain parties did well in different places at the last general election.

What's more, there have been big changes in the opinion polls since 2017. On average in the polls, the Labour vote has dropped by 10 percentage points since the last election, while the Lib Dem vote has increased by six points.

This suggests the Lib Dems may have overtaken Labour in as many as 55 of the 273 seats where Conservatives are defending and Labour came second last time.

Tactical voting websites

At this and previous elections there have been constituency polls to guide people in some high profile places. Now there are also sophisticated statistical models of polling data attempting to show how support for the parties stands in every constituency.

These models have been used by campaign groups to set up websites encouraging people to vote tactically for particular parties in particular constituencies.

Some go so far as to organise vote swapping - matching people from different constituencies so they can both vote tactically, knowing that someone somewhere else will be voting for their preferred party.

Tactical voting websites largely agree on which pro-Remain parties are best placed to win in which constituencies, but they do not entirely agree.

There have also been changes in public opinion since those websites were set up, and there might well be further changes before election day. And, of course, all polls and forecasts may be inaccurate.

So tactical voting websites cannot be entirely relied on. Voters have to form their own judgements as to whom they want to vote for and why.

Follow election night on the BBC

Watch the election night special with Huw Edwards from 21:55 GMT on BBC One, the BBC News Channel, and BBC iPlayer

It will also be shown on BBC World News and streamed live on the BBC News website internationally

As polls close at 22:00, the BBC will publish an exit poll across all its platforms, including @bbcbreaking, external and @bbcpolitics, external

The BBC News website and app will bring you live coverage and the latest analysis throughout the night

We will feature results for every constituency as they come in with a postcode search, map and scoreboards

Follow @bbcelection, external for every constituency result

From 21:45 GMT, Jim Naughtie and Emma Barnett will host live election night coverage on BBC Radio 4, with BBC Radio 5 live joining for a simulcast from midnight

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Stephen Fisher is associate professor in political sociology and a fellow of Trinity College, Oxford

Edited by Ben Milne