General election 2019: A matter of mistrust?

- Published

Are pork pies more common than humble pie in modern politics?

Do party leaders and politicians - British ones, mind you, not just dodgy foreigners - ever lie?

Well, you could perhaps duck the question and argue that our political leaders sometimes distort the truth.

Or you could say they like to present only a useful portion of the whole picture. And you'd be right about that.

But do they lie?

Is the Queen's Speech required viewing in the Corbyn household?

This week, if you even try to argue politicians never lie, you'd have to accept that Jeremy Corbyn, a dedicated, life-long republican, sits in front of the TV at home on 25 December and dutifully watches Her Majesty's Christmas message.

Then you'd have to believe his loyal colleague Angela Rayner was right to say her boss maybe watched the Queen's Message on catch-up TV on Boxing Day.

That was to explain Mr Corbyn's apparent claim that he somehow watched in the morning, hours before it's broadcast.

What did the PM hear in Hertfordshire?

Then, you'd need to accept Boris Johnson's word that, at the Nato summit in Hertfordshire on Friday, he had somehow never heard a word of his fellow national leaders huddling together in Buckingham Palace the previous evening, mocking US President Donald Trump.

He was captured on camera standing with them at the time, and joining in the joke.

I could go on. But I won't, because you'd arguably be asking the wrong question.

Mr Johnson's critics coyly accuse him of maintaining a "casual relationship with the truth".

But in fact it's fairer to say our politicians often have a transactional relationship with the truth.

In different ways, they constantly trade-off their duty of service to honesty against their personal and political advantage and disadvantage. Sometimes it's a fine judgement.

When it comes to such things as Mr Corbyn's viewing habits on Christmas Day, or whether Mr Johnson should have freely admitted gently mocking Donald Trump to the world's media at an international summit, how much do we really blame them?

How high are Jo Swinson's hopes as the campaign comes to a close?

If we're being honest, that is.

So, maybe the real question this week is: has the line between truth and untruth been consciously blurred to the point that whatever may be left of any trust between people and politics is now in jeopardy?

The answer to that, it's fair to argue this week, could be yes.

If watching TV on Christmas Day or ducking a potentially embarrassing question about Mr Trump are forgivable, or a least understandable, the prime minister was taking a risk again on Sunday when he insisted in his Sky News interview with Sophy Ridge that there would be no border checks between Britain and the island of Ireland under his Brexit deal.

Experts and his own fellow ministers admit that there'd have to be checks to comply with EU and international law, to guard against smuggling of endangered species, say, or unlawful trade with sanctioned regimes. They can't all be right.

If Mr Johnson ends up back in office, and requiring the support of the Democratic Unionist Party to stay there, he'll have to confront the truth of this question and it won't be a comfortable moment.

Mr Corbyn and his party's claim that Labour will tax only the richest 5% of society to pay for their expensive promises could also lead to a reckoning. The Institute for Fiscal Studies judges that the claim is implausible.

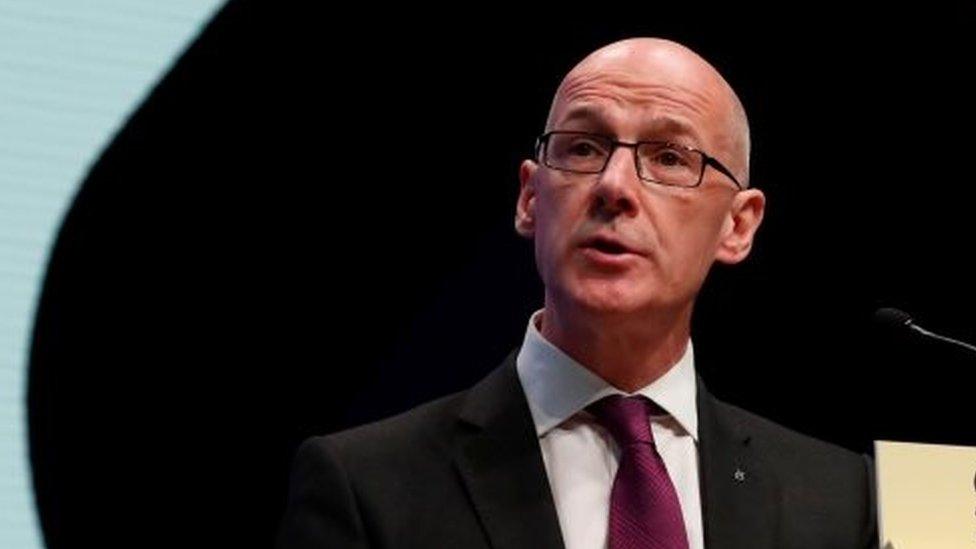

John Swinney said Trident was a "red line" for the SNP

All of this could perhaps be discounted were it not for the fact that the relationship between people and politics is already close to breaking point.

A Kantar poll this week found around half (48%) of those intending to vote Conservative on Thursday felt the Tories were "the best of a bad bunch". About the same proportion (49%) said the same of Labour.

The parties are running out of rope.

To be fair, the Liberal Democrats' early campaign claim to be running to install Jo Swinson in Downing Street can't really be described as a lie. Just faintly absurd.

She now says her aim is to make "real progress". In theory, the Lib Dems could gain only a small handful of seats on Thursday, even lose a couple, and still be very influential in a hung Parliament.

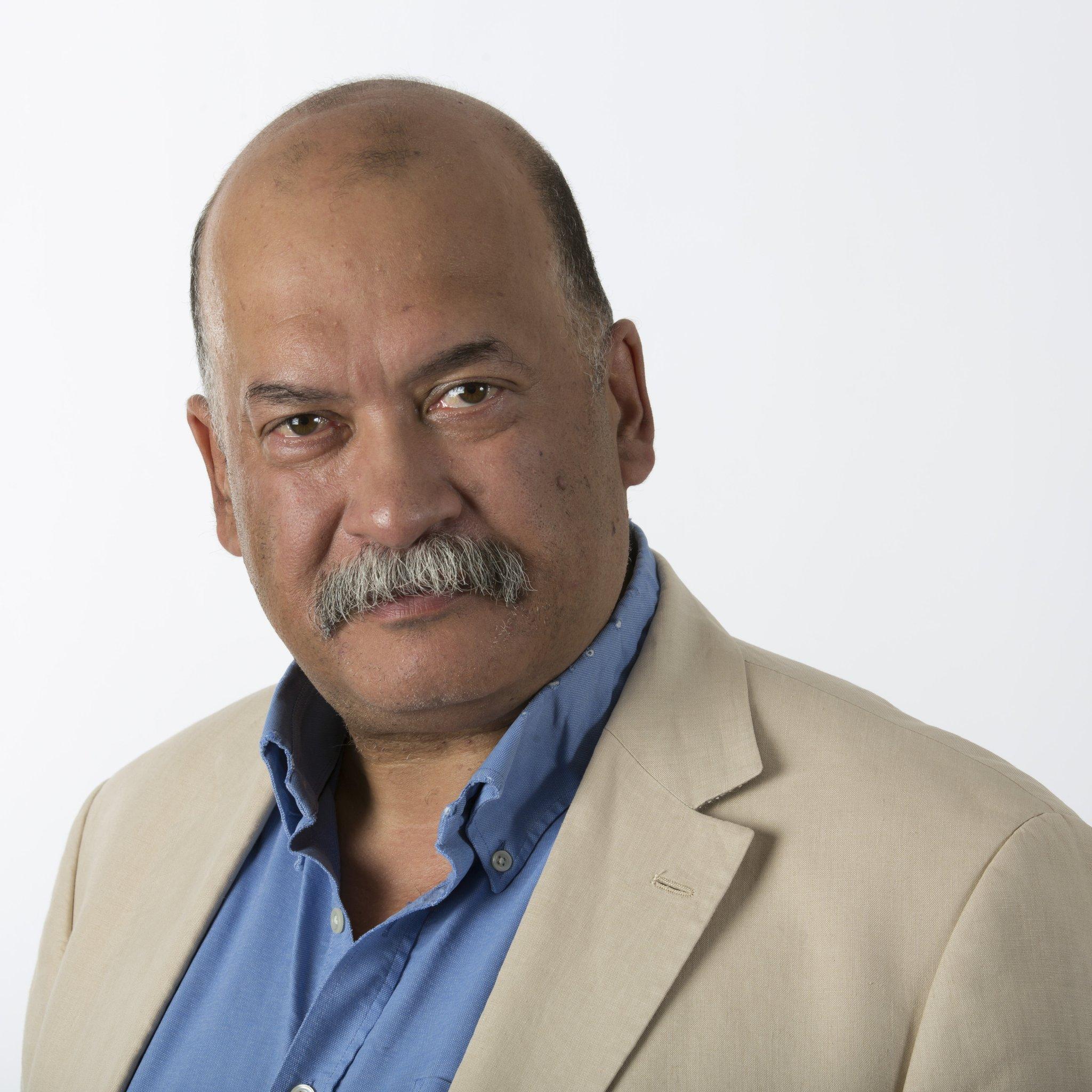

And for the SNP, Scotland's Deputy First Minister John Swinney told me on Pienaar's Politics on BBC 5 live that his party's demand for unilateral nuclear disarmament and the removal of the Trident nuclear submarine base at Faslane would be a "red line" in negotiations with Labour, if Mr Corbyn ends up casting around for support.

If it happens, that would be an interesting negotiation.

Where have they been?

Trace the leaders' travel map this week and Mr Johnson moved away from the North and towards the South-East and East for the first time.

His poll ratings look reasonably good, but five of his six visits this week were to Conservative-held seats.

Ms Swinson went to her first Lib Dem seat in Edinburgh West.

SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon visited her first Labour seat at Midlothian.

Is there a subtext here?

Meanwhile, Mr Corbyn prioritised visual impact over parliamentary maths.

He spoke of big tech, for example, at an Amazon depot, and he talked about inequality in front of a statue of Robin Hood.

Subtlety has its place. Just not on an election campaign.

- Published30 November 2019

- Published1 December 2019

- Published28 November 2019

- Published11 December 2019