Analysis: A mandate for Scottish independence?

- Published

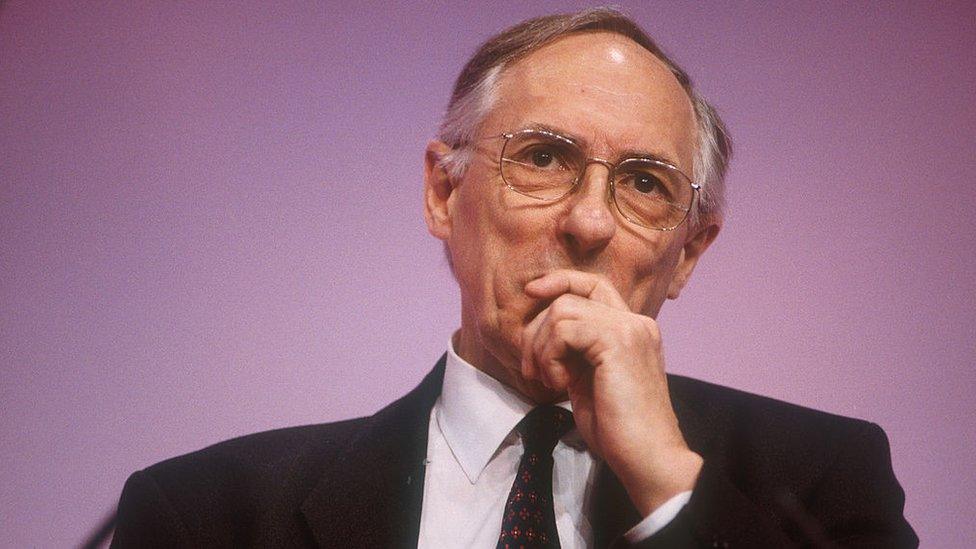

Labour's Donald Dewar was the inaugural Scottish first minister

The issue of mandates has a venerable pedigree in Scottish politics. Venerable, but not always clear and sharp.

During a previous period of Scottish Labour frustration, the late Donald Dewar briefly flirted with the suggestion that the Tories had no mandate to govern Scotland, given their relative lack of MPs north of the border.

It swiftly occurred to the astute Mr Dewar that this was not an argument which sat at all easily with a Unionist perspective. It was duly dumped in favour of another more straightforward push for devolved self-government.

At the core of the Dewar dilemma there was a philosophical and psephological problem.

By challenging the Tory mandate, he was positing an argument based upon the presumption that Scottish voting held unique and unchallenged sway.

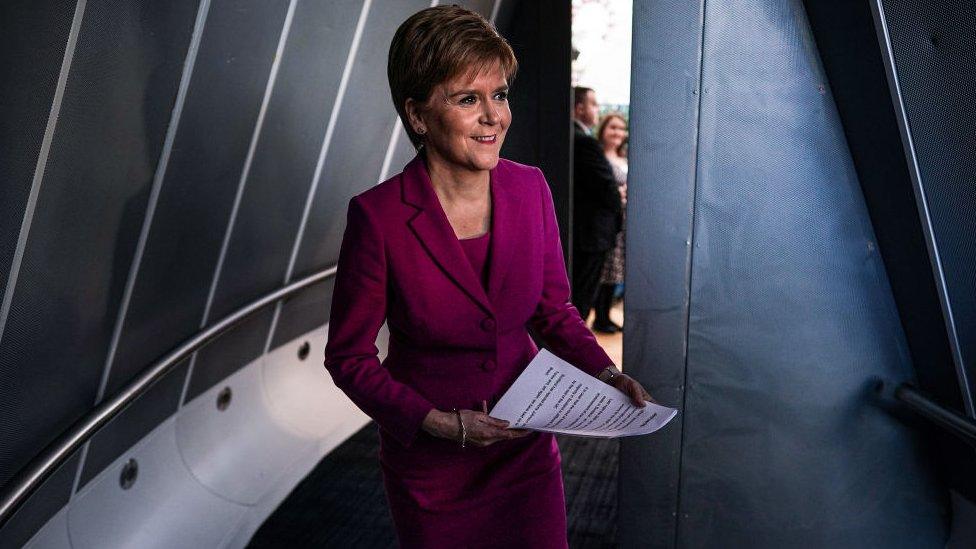

Nicola Sturgeon prespares to address the media after the SNP's impressive general election performance

A supporter of the Union will always argue - must always argue - that the Scottish perspective sits within and alongside the concerns of that wider UK electorate.

That fundamental argument is now back. In truth, it never went away. Nicola Sturgeon says she has a mandate to hold a further referendum on Scottish independence.

She says that mandate arises from a Holyrood vote, following her party's return to devolved power on a manifesto in a Scottish election which reserved the right to revisit the independence plebiscite if Scotland were to be taken out of the EU against the will of her people.

'Stunning victory'

Overnight, she enhanced that argument somewhat. She said she now had to accept, with regret, that Boris Johnson had a mandate to take England out of the EU.

That mandate, she insisted, did not extend to Scotland. Indeed, by contrast, her party's stunning victory north of the border argued the exact contrary.

Now, from her perspective, this is all entirely understandable. She posits a Scottish voting bloc. She takes her instructions - strictly, her mandate - solely from that Scottish bloc.

Jackson Carlaw said he would support a no-deal Brexit

This is, of course, fundamental for the leader of her party. The clue lies in the name.

But, as Ms Sturgeon knows very well, no Unionist can accept such a mandate, at least not without qualifying it in the context of that Union.

So Tories - and others who support the Union - will say that Scotland voted, in 2014, to remain within the United Kingdom - and that the UK as a whole has just elected a Conservative government, with an instruction, a mandate, to get the UK out of the EU. Entire, as a whole.

Fundamental division

Again, as Ms Sturgeon well understands, this fundamental division cannot be elided. It cannot be wished away.

And it now exists formally again. The returned prime minister has yet to say much, if anything, about Scotland, while basking in his UK victory.

But Jackson Carlaw, the interim Scots Tory leader, has said plenty. He insists that the Tories have been instructed to stand firm in defence of said Union. And they will do so, rejecting Ms Sturgeon's pressure for indyref2.

Ms Sturgeon will continue to insist upon her mandate, challenging her rivals to stand down, to give way. The Tories will continue to insist upon their UK mandate.

That way lies political stasis, at least in the short term. Ms Sturgeon wants a legally sanctioned referendum, not an unofficial ballot.

Given that, it is difficult to see what precise actions lie available to her. I think a law suit is improbable. The law is clear. The power to call a constitutional referendum rests with Westminster in the Scotland Act.

Momentum

So perhaps, instead of mandate, we should consider momentum. Political muscle.

Ms Sturgeon's clout has palpably strengthened. She won more seats, more votes. She has evident momentum.

Consider the alternative. Had she lost votes and seats, the air would have been rich with supporters of the Union claiming that the case for indyref2 had gone backwards.

It has plainly gone forwards. If the Tories continue to resist, as they say they will, then this will, at the very minimum, be a core question at the next Holyrood elections in 2021.

Which is scarcely good news for other parties in Scotland as it will tend to polarise Scottish opinion still more sharply between the SNP and the Tories.

Richard Leonard and Jeremy Corbyn during Labour's Scottish conference in March

Labour, for example, has suffered a catastrophic result in Scotland, partly through a failure of leadership, but partly through vacillation on the two big issues of Brexit and independence.

As Kezia Dugdale said on the excellent BBC Scotland election results show (whaddya mean, you weren't watching?), if you stand in the middle of the road, you tend to get knocked down.

There will now be a period of soul-searching within Labour. The self-styled People's Party failed to persuade anything like enough people to support it.

'Almighty rammy'

By soul-searching, I mean an almighty rammy. But a rammy with nuance. Mr Corbyn is going, perhaps with a gentle push to ensure he moves over sooner.

But what of Richard Leonard? He has his critics - who say the party organisation in Scotland was lamentable, the seat targeting implausible and the message incoherent.

But, for now, those critics seem disinclined to move for Mr Leonard's replacement. The thought seems to be that they want the Left to "own" defeat, just as the Left were keen to trumpet the failure of other, earlier leaders.

Lib Dem leader Jo Swinson lost her East Dunbartonshire seat

Then there will be an endeavour at reform, including clarifying the party's stance on constitutional issues.

Some, like Lesley Laird on that same excellent programme, will lament that. They say these constitutional issues are a distraction.

As I noted on the same… (OK, enough plugs), that sounded to me exactly like the Tories. Devolution never mentioned on the doorsteps No appetite. They kept that refrain going up to the moment when they lost every Scottish Westminster seat in 1997.

And the Liberal Democrats. A sigh of relief at holding on to three seats. A whoop of delight at taking North East Fife. And a yell of despair at Jo Swinson's defeat.

But they are still there. Still in play. In a game, which just changed the rules again.