General election 2019: Five lessons from the 'social media' election

- Published

Dominic Cummings, whose portrayal in a Channel 4 drama helped build a certain mysticism around Facebook's influence

There is still a vast amount we simply don't know about how the election campaign played out digitally.

This includes how much was spent by the main parties on targeted Facebook ads in the final few days; how much was spent advertising on other platforms; and whether foreign actors were behind any of the most controversial activity.

Nevertheless, based on a huge amount of collective data and the combined efforts of journalists and analysts across many institutions, we can now make some firm conclusions, in addition to those made already by my excellent colleagues at BBC Trending.

1. Targeted ads aren't everything

The Conservatives used banner advertising on YouTube

A certain mysticism has grown around the issue of targeted ads on Facebook, in part because of the Cambridge Analytica scandal and Benedict Cumberbatch's portrayal of Dominic Cummings in a Channel 4 drama. It has become a burning issue, fuelled by the fact Facebook went significantly further than other platforms in improving the transparency of their political ads - though there is still a great deal that we don't know - including who is ultimately funding them.

Fascinating analysis by Who Targets Me, external shows - against expectations - the Conservatives actually spent significantly less than Labour or the Lib Dems on targeted ads on Facebook. This despite having probably raised more money overall.

We can't scientifically prove the effect ads have on persuading voters; but it is striking that the Lib Dems, who had a bad election, spent more than the Conservatives, who had a great one.

At the same time, the Conservatives paid for a banner ad on newspaper websites and YouTube, meaning at one point anyone in the UK who visited YouTube saw their advert. We don't know how much this cost. But it is a more conventional, broadcast approach to advertising, rather than the hyper-targeted, constituency level ads you get on Facebook.

Why might this be?

2. Groups chats are full of persuadable voters

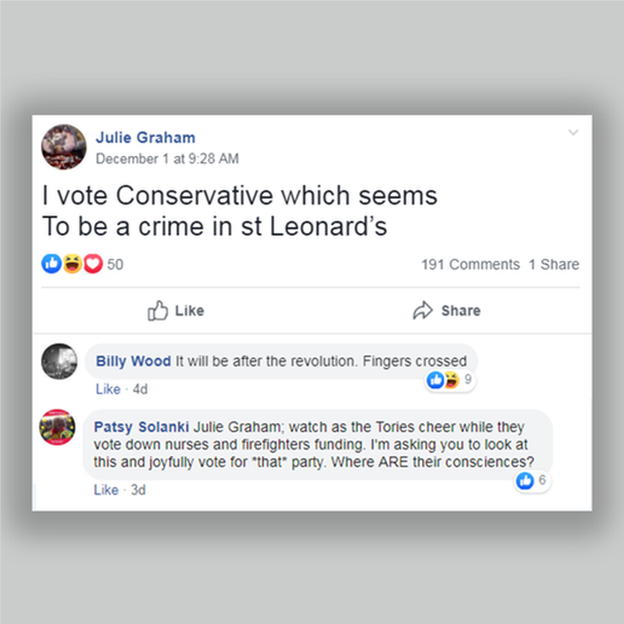

Local Facebook groups have been the battleground for bitter political debate

One reason might be that Tories have intuited that people are spending more time within open or closed group discussions - including on Facebook-owned WhatsApp - than scrolling through news feeds.

In April, Mark Zuckerberg gave a landmark speech in which he said the internet was moving into a new era where private groups rather than public discussions dominated. And the thing about private groups is that they may be more likely to contain persuadable voters - particularly if the groups weren't set up for explicitly political reasons.

Compare with Twitter. Very broadly speaking, Twitter is a news stream proliferated by people of strong opinions who already have a political world view and are likely to know how they'll vote. But a local Facebook group in Morpeth, or Hastings, or some other marginal, which may have been set up to talk about local issues, is more likely to have people who aren't political, and could be swayed.

Some of these groups contain several tens of thousands of people - huge numbers in a marginal constituency. And while many journalists wrongly think of Facebook as a rolling news feed above all else, news is in fact a tiny part of Facebook: group discussions are where most of the activity on Facebook happens.

Put that together with changes Facebook has made to de-prioritise news and prioritise "meaningful interactions" - that is, stuff from friends and family - and you can see why these groups are key to understanding that platform.

Extensive reporting by my colleagues at BBC Trending and BBC Monitoring suggests that, during this election, a huge proportion of the national conversation was happening in these often more localised groups, far from public scrutiny. Getting inside these groups may become a priority for the MPs of the future.

3. Twitter had a bad election

No two Twitter users have the same experience, because all follow different people. But I think Piers Morgan was correct to say "Twitter loses another election" last night, though perhaps for more complex reasons than he implied.

What he and others believe is that Twitter has a liberal bias, and that it can too often be a chat room for the metropolitan elite. That is my experience too, despite my best and constant attempts to follow people outside - and I use the phrase after long consideration - the London media bubble. If Twitter does seem like it's dominated by journalists from Remain-ish titles, or Corbyn supporters, well, both had a bad night.

The main reason that Twitter had a bad election, however, is that it continues to be a handmaiden to appalling abuse and the proliferation of fake news. As a stream, Twitter is great for real-time updates. But so much of what you see is digital sewage, with trolls directing unconscionable abuse at innocent or vulnerable people, and a detection and reporting system that is wholly inadequate.

Moreover, when the Conservative Party press account re-branded itself a fact-checking service early in the campaign - a dystopian tactic that was repeated last night - it is striking that it took to Twitter to, in effect, disseminate confusion. Sadly, it is a matter of fact in 2019 that the British party of government looks to Twitter to dupe people.

4. Foreign interference: too soon to tell

We know that the leaked US-UK trade documents about the NHS appear to have been put into the public domain by accounts originating in Russia - though possibly before the election campaign began.

We know that some of the attempts to spread disinformation, for instance around the picture of a four-year-old boy on the floor of a Leeds hospital, came from highly anonymised accounts that bear a discomforting resemblance to previous foreign operations that leant on bots.

But it is hard to trace this stuff. A comprehensive audit of digital foreign interference in this election is going to take several months yet.

5. The traditional media is good at going viral

The moment an ITV reporter confronted Boris Johnson with a photo of a sick child on a hospital floor

Election campaigns always strain relations between the BBC and the government of the day. The consequences of that are for another blog and day.

It is very interesting that many of the most viral clips on social media from the past few weeks were initially broadcast on traditional media. Andrew Neil's monologue about Boris Johnson's refusal to be interviewed by him, followed by an image of an empty chair, is one; Nicky Morgan's difficult interview about nursing numbers on Good Morning Britain, which really took off on Facebook and has had close to 14 million views, is another. And then there was Mr Johnson's interview with an ITV journalist who tried to show him that picture of a boy on a hospital floor.

It may be that, for all the talk of linear decline, traditional broadcast media still carries an authority and weight that makes clips from news bulletins or studio programmes more likely to go viral.

WHO WON IN MY CONSTITUENCY? Check your result, external

NATIONAL PICTURE: The result in full, external

ALL YOU NEED TO KNOW: The night's key points

MAPS AND CHARTS: The election in graphics, external

BREXIT: What happens now?

IN PICTURES: Binface, a baby and Boris Johnson