What's next for the Supreme Court?

- Published

It is difficult to overestimate the impact that the death of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia will have on US politics in the coming months. A vacancy on the court that serves as the final arbiter on legal and political controversies of all stripes, is always a significant, and significantly contentious, event.

This time, however, it has the potential to be a conflagration for the history books.

Here are answers to six questions about why this unexpected development is such a big deal - and what could happen next.

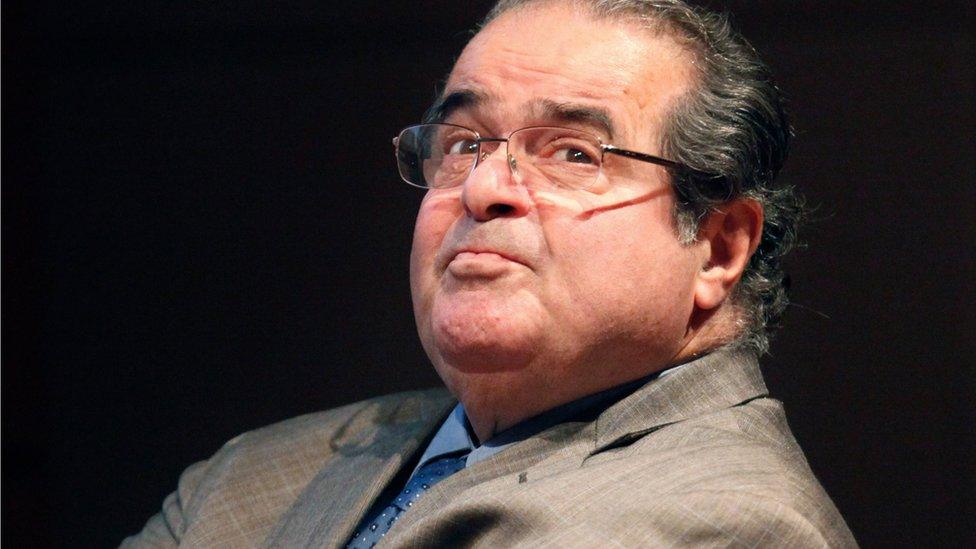

Former President Ronald Reagan and Justice Scalia are considered conservative icons

Why was Mr Scalia so important to the current Supreme Court?

With a Supreme Court closely divided between five conservative justices and four liberal ones, every person on the bench is critical. Many of the most groundbreaking Supreme Court decisions of recent times have been decided by the slimmest of majorities.

Justice Scalia, however, was more than just another court vote.

He was also one of the chamber's most outspoken advocates for conservative jurisprudence. He was a towering voice for the doctrine of originalism - that the text of the Constitution is immutable and not open to "modern" interpretations.

He was the author of District of Columbia v Heller, which struck down restrictions on handgun possession and held that the Second Amendment enshrined firearm ownership in the US as a constitutional right.

His fiery dissents, such as in recent cases on gay marriage and the constitutionality of President Barack Obama's healthcare reform, served as rallying cries for conservatives across the US.

The eight remaining justices could become deadlocked on some cases

What happens to the current term of the Supreme Court?

After a period of mourning, the court can - and likely will - continue to consider the cases already on its docket during its current term, which traditionally concludes at the end of June. That includes high-profile legal battles over contraceptive coverage mandates in federal healthcare law, state attempts to increase regulation of abortion providers, the consideration of race in college admissions and Mr Obama's executive action on immigration.

With only eight justices, however, the court could end up splitting four-to-four on many of the more contentious cases. If that happens and no position commands a majority in the court, then the court's opinions will hold no legal weight. The lower court ruling being reviewed will continue to stand in its jurisdiction.

In other words, on the biggest, most divisive legal controversies of the day, the court could be effectively powerless until a ninth justice is named. At that point, the court could decide to take another look at the issues where it was deadlocked.

Judge Sri Srinivasan serves on the federal circuit court in Washington

Who might Barack Obama pick to replace Justice Scalia?

This will be the great parlour game for the coming weeks in Washington, as speculation abounds over whom Mr Obama could pick.

Mr Obama has had two Supreme Court openings during his presidency. He chose Elena Kagan, the White House's top litigator, and Circuit Court Judge Sonia Sotomayor.

Presidents often turn to the federal circuit courts - one step below the Supreme Court - for their nominees. If Mr Obama does so again, fashionable names include Sri Srinivasan, an Indian-American on the District of Columbia Circuit, Jane Kelly of Eighth Circuit and Paul Watford of the Ninth Circuit.

All are young - which is key when seeking Supreme Court longevity - and popular among liberals, while not having a controversial judicial track record that could be picked apart by conservatives.

Supreme Court justices don't need to have an extensive background in the judicial branch, however.

California Attorney General Kamala Harris is another name that has been floated as a possible Supreme Court nominee, although she's currently campaigning to replace Barbara Boxer in the US Senate.

Potential Supreme Court justices undergo a thorough vetting process in the Senate

How is a replacement justice confirmed?

Normally, if a vacancy opens up on the court, the president will name a successor after a few weeks of consideration. At that point, the US Senate Judiciary Committee will hold hearings in which the nominee is extensively questioned. Then the entire Senate votes on whether to approve the nominee.

Although a simple majority of the 100-member Senate is necessary for confirmation, senators could "filibuster" the pick - a procedural manoeuvre that effectively raises the bar for approval to a three-fifths majority.

The last time that happened was in 1968, when Republicans - then a minority in the Senate - blocked President Lyndon Johnson's nomination of Abe Fortas to be chief justice.

The opening occurred in President Johnson's last year in office and was contingent on the current justice, Earl Warren, retiring. After the Republicans filibustered the October vote, Warren delayed his retirement - and the new president, Richard Nixon, chose his successor.

There has been talk in the past that the filibuster could be ended for Supreme Court nominations, as it has been for nominations to lower courts, but doing so would require reversing more than half a century of Senate precedent.

The outrage from such a move at this juncture would be white-hot, however.

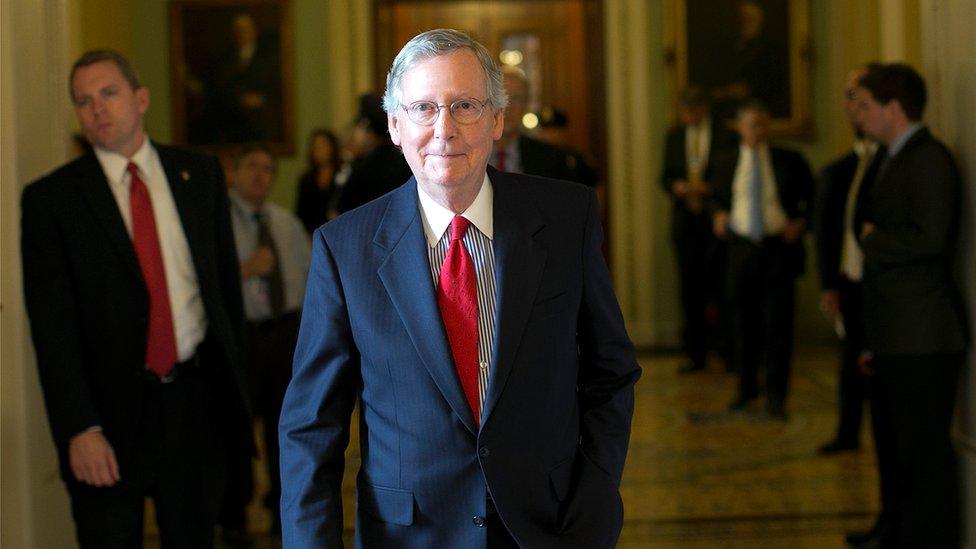

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell says the confirmation should wait until the next president is elected

How could this time be different?

Because Justice Scalia's death comes just 11 months before the end of Mr Obama's term as president, Republicans in the Senate are going to be under intense pressure from some conservatives to do everything they can to delay confirmation of a replacement until a new chief executive is sworn in on 20 January 2017.

That could involve slowing down confirmation hearings in the Senate committee and filibustering any nominee before they receive a vote in the full Senate.

Then, conservatives hope, a Republican president would name a replacement more likely to maintain the one-vote conservative majority on the Court.

The longest it has ever taken the Senate to hold a vote on a Supreme Court nominee is 125 days, but there are indications this time could be different.

Already Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky has issued a statement that, while not definitive, shows his preference.

"The American people should have a voice in the selection of their next Supreme Court Justice," he said. "Therefore, this vacancy should not be filled until we have a new president."

A staffer for Senator Mike Lee, who serves on the Senate Judiciary Committee, tweeted , externalthat the chances of Mr Obama successfully appointing Scalia's replacement were "less than zero".

The question of the next Supreme Court justice should shake up an already chaotic presidential race

What does this do to the US presidential campaign?

Justice Scalia's death will likely douse petrol on what already was a raging fire of a presidential campaign.

If Republican senators are able to delay confirmation until the end of Mr Obama's term, November's election will in effect determine the political orientation not only of the US presidency, but the Supreme Court as well.

A Democratic victory in November means a court with a decidedly more liberal bent. If Republicans prevail they preserve their slender conservative majority on a court that regularly issues landmark decisions on issues like gay rights, immigration law, healthcare reform, campaign finance reform and civil liberties.

Already several Republican candidates for president have called for delaying consideration of Justice Scalia's replacement until Mr Obama's successor takes office.

"The next president must nominate a justice who will continue Justice Scalia's unwavering belief in the founding principles that we hold dear," Florida Senator Marco Rubio said in a statement.

"Justice Scalia was an American hero," tweeted Texas Senator Ted Cruz, external. "We owe it to him, and the nation, for the Senate to ensure that the next president names his replacement."

Both Democrats seeking the presidency, Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders, regularly talk about the future of the Supreme Court while on the campaign trail. Mr Sanders has repeatedly said he will only appoint justices to the court who pledge to overturn Citizens United , a landmark case that eased restrictions on corporations and unions giving money in support of political campaigns.

Even if Mr Obama gets his nominee through the Republican-controlled Senate, American voters will be keenly aware of the stakes involved.

With three of the eight remaining justices over the age of 70, the Supreme Court battle of 2016 will likely be replayed again in the not-too-distant future. Depending on who is president, it will be fought over whether the court moves to the left or the right.