Why we should have seen Trump coming

- Published

On Super Tuesday Donald Trump's hostile takeover of the Republican Party should come even closer, and like stiff-collared executives in some wood-panelled boardroom trying belatedly to fight off a corporate raid, the GOP high command seems incapable of stopping him.

For them, Super Tuesday could become Black Tuesday. Friday must have been gloomy enough, when Chris Christie, supposedly a card-carrying member of the establishment, kissed Donald Trump's hands and gave this political outsider his endorsement.

Christie's blessing came as a bolt from the blue, and taught us once more to expect the unexpected. But shouldn't the establishment - and us in the media, for that matter - have seen the billionaire coming? After all, for years the Republican standard bearers have been vulnerable to a challenge from an anti-establishment candidate.

Before going on, we should say what we mean by the Republican Party establishment, a term regularly bandied around but rarely explained. Fifty years ago, it was easier to identify.

It was an eastern establishment dominated by Wall Street bankers and corporate executives, who were strongly pro-business, ideologically moderate and politically pragmatic.

Nelson Rockefeller in 1965

Nelson Rockefeller, the scion of the banking dynasty and Governor of New York - who lived, like Donald Trump, in great splendour on Fifth Avenue - was their figurehead.

These days, however, the Republican establishment is harder to define and more diffuse, which also explains why it is easier to topple.

More on Trump and the Republican race for the White House:

Anthony Zurcher: Day one of the Republican civil war

Commonly it is broadly taken to mean the Republican National Committee, senior office-holders (like Chris Christie), present and past, conservative lobbyists, like the US Chamber of Commerce, big-money donors and opinion-formers, who write for publications like the Weekly Standard, the National Review and op-ed pages of the Wall Street Journal. But that definition is open to debate. Its disparate membership explains its inability to exert control.

Mitch McConnell is not a fan of Trump

The most obvious reason for the decline of the Republican establishment has been the rise of anti-establishment adversaries. The Tea Party, an insurgent grassroots movement that emerged after Barack Obama's inauguration, has posed the most serious threat.

Its hatred of the president is matched almost by its loathing for establishment Republicans in Washington, like the Senate Majority leader Mitch McConnell, who activists complain could have done more to thwart the White House.

Tea Party primary challengers have ousted senior establishment fixtures, like Senator Richard Lugar, who represented Indiana for 36 years.

The "Hell No" Caucus on Capitol Hill, a rump of 50 or so Tea Party-backed Republican hardliners in the House of Representatives, was strong enough to push the former House Speaker John Boehner to the point of resignation.

As for opinion formers, most of the loudest and dominant voices in the modern-day conservative movement, like the talk show hosts Rush Limbaugh and Glenn Beck and the commentator Ann Coulter, are vehement critics of the establishment.

John Boehner resigned from the top Republican position in the House of Representatives last yaer

The Fox News channel, even though it has often given a platform for anti-establishment voices, doesn't fall into that same category. But it has become a rival power centre, outside the control of the GOP high command.

Going into the 2016 campaign, there were big clues that establishment candidates would be vulnerable. Eric Cantor, the House Republican majority leader, was ousted, unexpectedly, ahead of the 2014 congressional mid-terms. Boehner was pressured to resign as House Speaker.

However, most of us made the mistake of interpreting the results of the congressional mid-term elections as a major setback for insurgents, because they failed to make more breakthroughs.

Their attempt, for example, to oust the Republican Senator Thad Cochran in Mississippi, then a six-term incumbent, was unsuccessful. In Kentucky, Mitch McConnell also crushed a Tea Party challenge in the Republican primary.

According to polls, Tea Party favourites, like Sarah Palin and Michelle Bachmann, also lost their lustre.

The Tea Party movement emerged after the election of Barack Obama

Even though the Tea Party was waning - in October last year, a Gallup poll suggested its support had dwindled to just 17% - the anger and rage that gave rise to it had not gone away.

Conservative insurgents just needed a better candidate and more effective mouthpiece.

The most obvious figure was Ted Cruz, a long-time darling of the Tea Party. But Donald Trump has proved more adept at giving voice to the politics of frustration and rage, even though he is not a Tea Party candidate per se.

Long before announcing his presidential bid, the billionaire had already burnished his reputation among Tea Party devotees by becoming the most prominent "birther" - claiming, falsely, that Barack Obama is not a natural-born citizen of the United States. His outspoken attacks on Mexicans and Muslims, combined with his contempt for political correctness, are music to insurgents' ears.

Another analytical failure was to assume that the Republican establishment could do in 2016 what it has done successfully in the past seven presidential elections: to see its anointed favourite become the nominee.

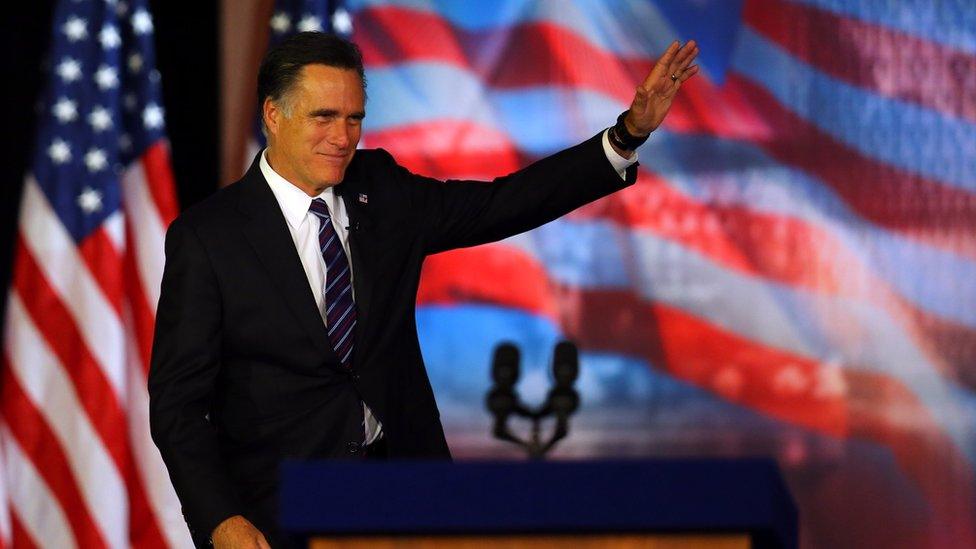

Mitt Romney was seen by many as an uninspiring but electable candidate - but lost soundly to Barack Obama

George Herbert Walker Bush, Bob Dole, George W Bush, John McCain and Mitt Romney. All were Republican establishment favourites. What's perhaps most remarkable about that run of success for the party's high command is that it continued so long.

We should have paid more attention to the difficulty Mitt Romney had securing the nomination in 2012 and also the extent to which he was assisted by the absence of a strong establishment rival.

A central problem for the GOP high command this year, of course, has been that Marco Rubio, John Kasich, Jeb Bush and Chris Christie have split the vote.

Not only that, we should have been more mindful of Rick Santorum's surprise showing four years ago. The right-wing former Pennsylvania Senator won 11 states and four million votes, even though he was viewed at the outset of the race as a woefully weak candidate.

It suggested that the Republican establishment would face a more serious problem in 2016 if a more compelling right-winger emerged.

Besides, one of the reasons why anti-establishment fervour is so strong this time round is because the grass roots is so fed up with being saddled with establishment moderates, like Romney.

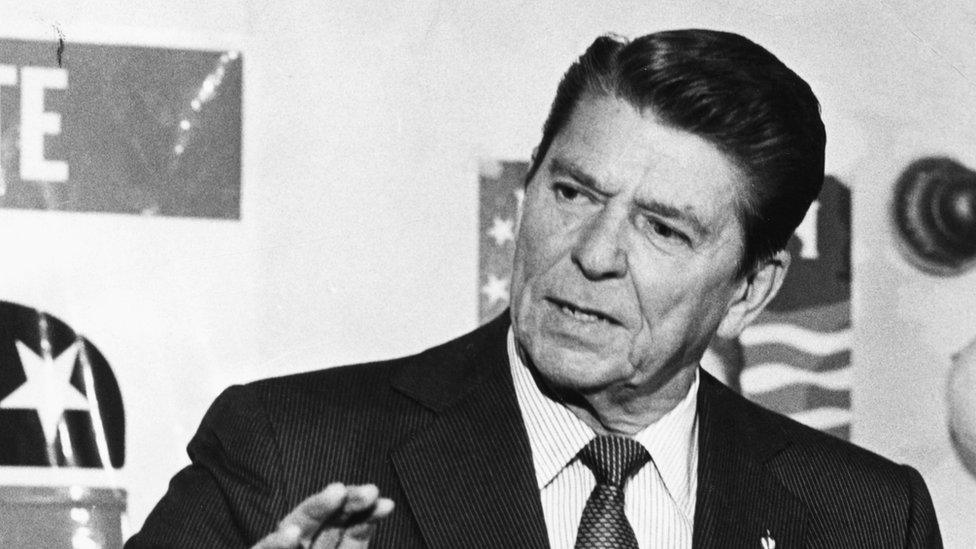

Ronald Reagan in 1980

Had we reached further back into Republican Party history we would have seen that hostile takeovers have succeeded in the past.

In 1980, Reagan ran as an anti-establishment candidate, beating the blue-blood Republican George HW Bush, a scion of the establishment.

Then there was Barry Goldwater's success in 1964, when he scored that highly symbolic victory over Nelson Rockefeller, the great pillar of the establishment.

The victory of an Arizonian right-wing firebrand over a New York moderate personified the shift in the Republican Party's centre of gravity during the civil rights era from the north-east to the south and south-west.

It changed the character of the party, setting it on its present course.

Revulsion right now of the permanent political class and party elites seems to be a global phenomenon, but in America it is particularly pronounced, on the left as well as the right.

But an anti-establishment figure like Donald Trump would not have become so strong had not the party establishment become so weak. The GOP, the Grand Old Party, has been ripe for a takeover for years.