US election 2016: When are election polls most reliable?

- Published

Making history: One of these two will make it to the White House

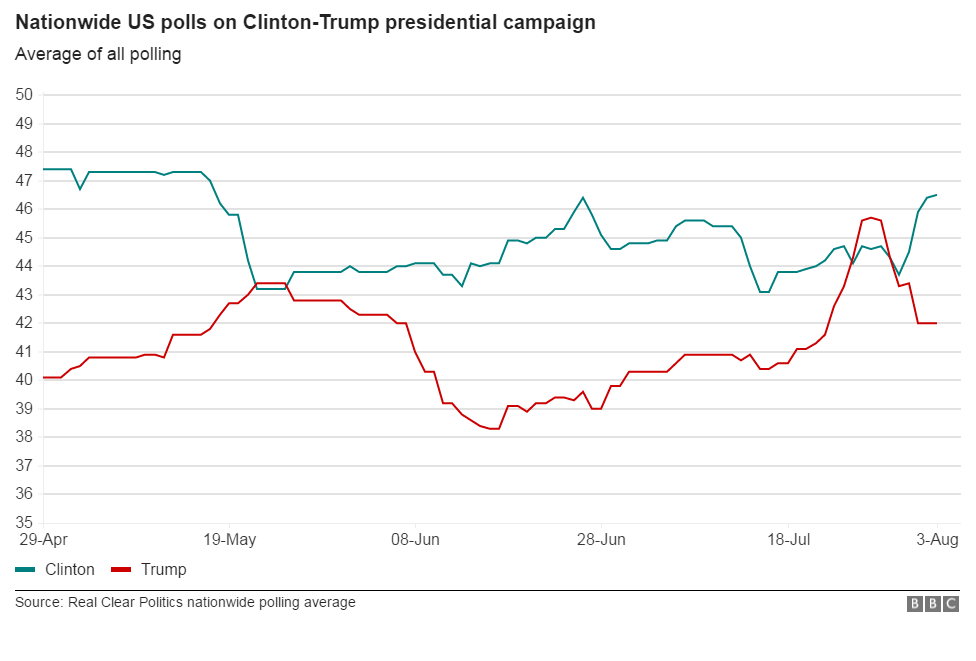

A new round of US election polls have shifted momentum behind Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton in the three-month dash to November.

Seven national polls conducted after the close of the Democratic convention last week showed the former secretary of state receiving an average increase of nearly 7% compared with her pre-convention support.

Mrs Clinton's favourability ratings have also improved, rising to an average of four points to 41% in recent polls.

Though a larger share finds her unfavourable at an average of 53%, it is still four point less than it was before the convention.

But do the recent batch of surveys paint an accurate picture of what will happen when voters head to the polls in November?

Not quite, according to experts and pollsters.

While Mrs Clinton has gained a comfortable lead over Mr Trump, it will take more than polling to determine who will end up in the Oval Office.

Why are US presidential election polls so erratic?

Polls can't predict voter turnout

With hundreds of surveys tracking the election, US polls tend to be good at gauging American opinion, according Clifford Young, the president of US Public Affairs for Ipsos polling.

"We have the luxury of large numbers," Mr Young said. "That makes it better and easier for prediction."

However, all of these polls use different methodologies to survey Americans and one of the biggest challenges is determining who actually will cast a ballot in November.

"Polling is very difficult these days," said Brendan Nyhan, an assistant professor of government at Dartmouth College.

"It's hard to get a representative sample of Americans to take a survey online or by phone, and even if you do get a good sample, it's difficult to tell who is actually going to turn out to vote."

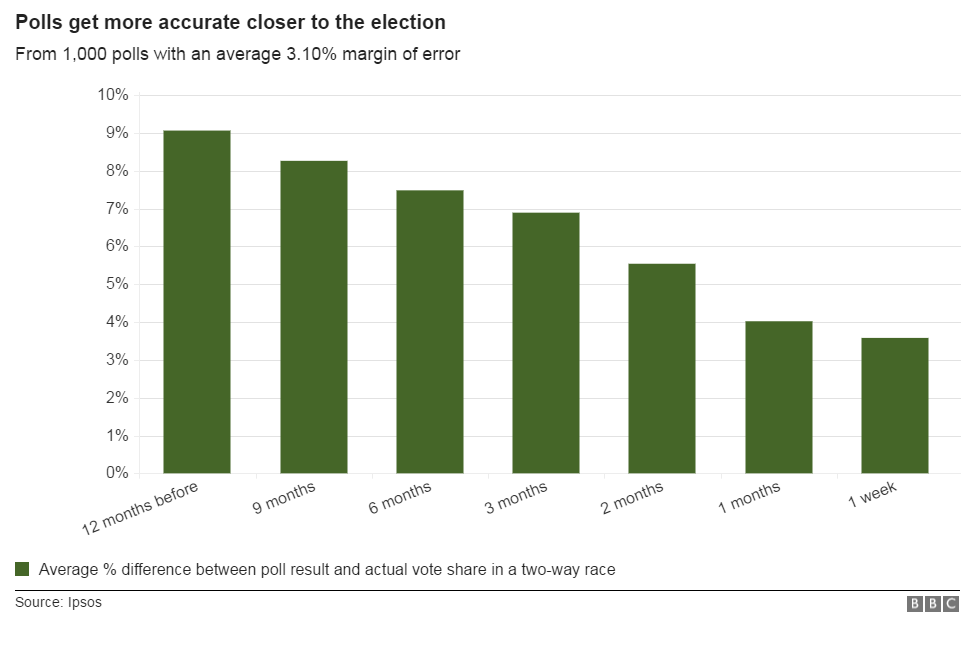

Research has also shown polls tend to be the least accurate the further they are from Election Day.

During the early stages of the primary election, parties have yet to select their nominee while voters may not necessarily be paying attention to candidates or the issues, Mr Nyhan said.

For example, polls conducted in January 2003 showed former President George W Bush ahead of Democratic Senator John Kerry by 8% and 17%.

However, Mr Bush finished just 2.5% ahead of Mr Kerry in the popular vote, the slimmest margin of a re-elected president since Woodrow Wilson in 1916, according to Mr Nyhan.

When do US presidential election polls become most predictive?

Accuracy improves in the weeks leading up to the election, when people are more likely to have made up their mind, research has shown.

However, surveys released a couple of weeks after the Republican and Democratic conventions, which took place back-to-back last month, is when numbers start to become reliable, according to experts.

Party conventions are often the starting point for wider public interest in campaigns, when party officials have an opportunity to rally behind their nominee and raise awareness on campaign issues.

"The conventions help remind people what the state of the country is and which side they're on," Mr Nyhan said.

However, Sam Wang, a neuroscientist and election analyst at Princeton University, warns that only polls that specifically survey people at the beginning and end of either convention can provide an accurate picture.

Though conventions are an important election marker, Mr Wang points out the public image of a candidate can change over the course of a campaign.

What is a convention bounce?

Convention bounces are often short-lived

Candidates often receives a "bump" or "bounce" in polls in the week following their party's convention.

For instance, candidates who are underperforming before the convention tend to receive larger bumps while candidates who are running ahead of where they are expected to be often receive smaller bumps.

The bumps, Mr Nyhan explained, helps bring the public closer to the expected outcome.

"The bounce itself doesn't necessarily determine the winner but it helps move it in the right direction," Mr Nyhan said.

But convention bounces tend to be short-lived and mainly come from party supporters.

Mr Trump enjoyed a brief post-convention bump before Mrs Clinton regained a solid lead at the end of the Democratic convention.

In fact, sometimes bounces just show how likely people are willing to respond to a survey or say they will support a candidate, but that does not mean they will show up at the polls.

How important are state polls?

The election will come down to a handful of states - including Iowa

While national polls can measure movement and general opinion, state polls provide a more nuanced glimpse of where voters stand.

"In a nation as ethnically diverse as the US, it's somewhat challenging to survey the whole country," Mr Wang said.

Consider the Electoral College, which assigns each state a number of electors according to its size.

The winning candidate needs to get a majority of 270 of the 538 electors to win the Electoral College vote.

In majority of US states, the winner takes all of that state's electors, which is why state polls play an integral role in election projections.

Particularly in the key battleground states such as Florida, Ohio and Pennsylvania, polls serve as an important bellwether to November's outcome.

President Barack Obama won all three of those states in 2008 and 2012.

What do the latest polls mean for November's outcome?

Recent polls show Mrs Clinton leading Mr Trump by 4.5%

While Mrs Clinton's bounce has given her a comfortable lead over Mr Trump, experts say whether it will stick will not be clear until the next couple of weeks.

However, her rise may be meaningful because there are not many events between now and November that are likely to change people's minds, Mr Nyhan added.

Still, the recent series of polls are more indicative in the short term of relative performance.

Mrs Clinton's bump may suggest she had a better convention performance, Mr Young said.

According to a recent Gallup poll, external, Americans said they were 45% more likely to vote for Mrs Clinton while 41% said they were less likely to cast their ballot for her after the Democratic convention.

In contrast, Gallup found the 2016 Republican convention marked the first time in history in which more voters said they were less likely to vote for a party's nominee after its convention.

In fact, 51% of those surveyed said they were less likely to vote for Mr Trump compared to 36% who said they were more likely to cast their ballot for him after the Republican convention.

Are this election's polls any different from previous elections?

This year's candidates are deeply unpopular

Though Mr Wang noted this year voter attention is unusually high, the last three elections have shown less movement in polls than in previous campaign years.

"Voter polarisation has gotten a lot stronger, which means voters are less and less likely to consider the other candidate," he said.

In fact, one indication is the size of the convention bounces, which have become notably smaller in recent election history.

According to Gallup, external, candidates saw an average convention bump of 6.2% from 1964 to 1992 while today they see an average of 3.8%.

However, Mr Young emphasises this year is a disruptive election, with campaigns marked by a stronger protest vote.

This year's forecasts must also take in account just how deeply unpopular Mrs Clinton and Mr Trump are compared with previous elections, which means it ultimately will rely on voter turnout.

"The desire to vote for neither candidate complicates things," Mr Young said. "The protest vote can have potential to really impact the outcome when it comes to the election."

As the 2016 presidential election has demonstrated, anything could happen in the race to the finish line.