Is the 2016 US election campaign racist?

- Published

Donald Trump to black voters: "What the hell do you have to lose?"

Election time in America usually resonates with boundless optimism, with candidates, in their own way, promising "morning in America", as Ronald Reagan once did.

Not this time. Not in this mean-spirited race. Not when the undercurrent is race in America.

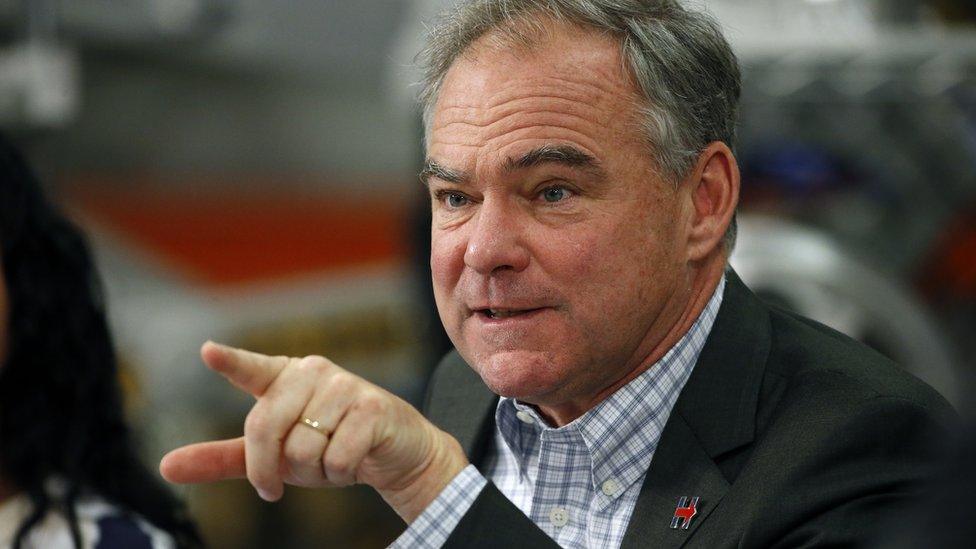

Who could imagine in 2016 that a vice-presidential candidate from one side would accuse the man running for president from the other side of pushing the "values of the Ku Klux Klan?" But that is what Tim Kaine said of Donald Trump, denouncing him, in effect, for wanting to restore white supremacy.

And this was not an isolated moment of campaign rhetoric.

Hillary Clinton accused Donald Trump of wanting to take the "hate movement mainstream".

And we have also had presidential candidate Donald Trump being asked by a television interviewer whether he wants white supremacists to vote for him. And yes this is 2016.

Kaine accused Trump of KKK values

And then Donald Trump rounds on his opponent: "Hillary Clinton is a bigot who sees people of colour only as votes."

And then, in the midst of this, Donald Trump takes a page out of his book, The Art of the Deal. He decided to make an extraordinary offer to black Americans. "You're living in poverty," he tells them. "Your schools are no good. You have no jobs. What the hell do you have to lose by trying something new like Trump?"

And, unsurprisingly, many black Americans have expressed outrage that their lives and struggles can be so easily dismissed.

There has been progress. More than 60% of black Americans have white-collar jobs, and 22% have graduated from college.

Yet despite real progress, 41% say there is still discrimination.

Eight years ago, in 2008, I stood in Grant Park, Chicago, when Barack Obama delivered his acceptance speech.

I wrote at the time "an African-American had denied the weight of history, and become the most powerful man in the world". Mr Obama spoke of "many voting for the first time in their lives, because they believed that this time must be different". He spoke of change coming to America, of reclaiming the American Dream.

And on inauguration day 2009, at 04:00 on a bone-chilling night, I saw thousands of people on the move, many of them black Americans, trekking from distant places to claim their place on the Mall and witness history being made.

So what happened? Inevitably hopes raised were disappointed.

The economy spluttered and the dream of attaining a middle-class lifestyle receded. Inequality rose. The levels of incarceration for black Americans, although diminishing, remain high. On the streets, many attempted arrests ended in police shootings.

And then I recalled too that some Americans never accepted Barack Obama as a legitimate president. I remember a Sarah Palin rally in Ohio in 2008 at which she declared: "Obama doesn't feel like us." There were references to the "real America".

On the cable television channels and in Congress, a mean-spiritedness has stained the political debate. Bipartisanship and collegiality and compromise have been ditched in favour of ideological battles.

And it seeps into this political season. At a Trump rally in Milwaukee a few weeks ago, several men had T-shirts with the slogan "Trump that Bitch!"

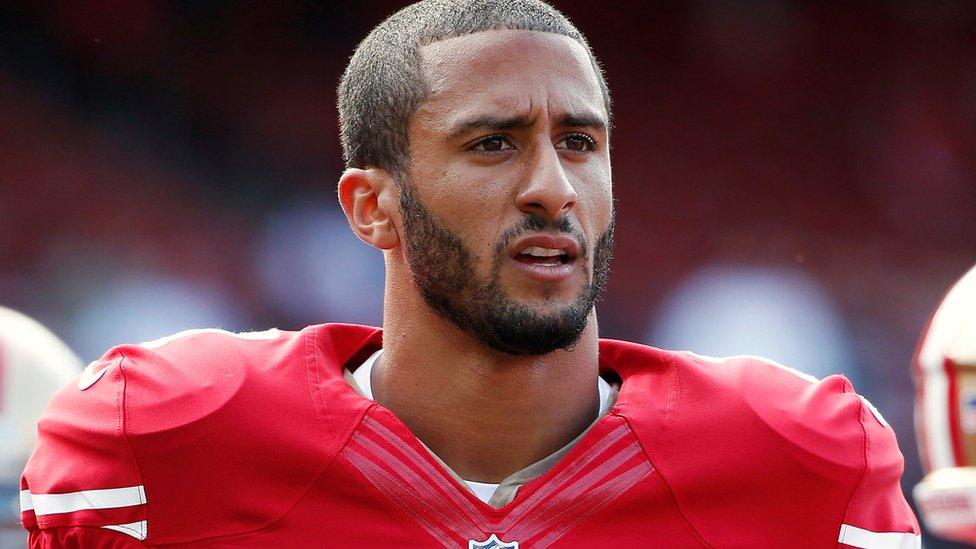

Kaepernick made the protest during an exhibition game (file picture)

And in the maelstrom of this campaign Colin Kaepernick, a San Francisco 49ers quarterback, remains seated during the national anthem. It is a protest, he says, against the nation's oppression of people of colour.

"There are a lot of things going on that are unjust," he said afterwards. "I mean," he continues, "you have Hillary who has called black teens 'super predators'. You have Donald Trump who's openly racist."

Both candidates would dispute this but race is one of the undertones of this campaign.

Martin Luther King's central hope was that people someday would be judged by "the content of their character" rather than the colour of their skin.

But this election is far from being colour blind. It is littered with references to college-educated "whites" or "black" women or Hispanics - as if what mattered was skin colour.

Back in 1964, the then Republican candidate Barry Goldwater agreed with the sitting president Lyndon Johnson that they would keep race out of the campaign and not exploit it for electoral purposes.

They were different times.