From reverential to strident... the two Donald Trumps

- Published

The Donald Trump who appeared in Mexico on Wednesday was vastly different from the Donald Trump we have grown used to seeing on the campaign trail.

And he was certainly unrecognisable from the candidate who roared his way through his long-awaited immigration speech the same day in Arizona.

Rather than flying into Mexico City in his usual private plane - Trump Force One, as it has come to be known - he was borne south of the border in a jetliner with an all-white livery that was not emblazoned with his surname.

It was a rare display of airborne humility. Rather than disparage Mexicans, as he has done repeatedly since announcing his candidacy in New York last summer, the crucible moment of his campaign, he complimented his hosts.

Rather than bark his way through a press conference, he was measured, hushed, almost reverential. It was almost as if he was speaking at a funeral.

Clearly he had taken on board enjoinders from advisors like Chris Christie and Rudy Giuliani, who urged him to make the journey to Mexico so that he could have a stab at statesmanship.

Enrique Pena Nieto shakes Donald Trump's hand during the Republican nominee's unexpected visit to Mexico City

But by the time he got to Phoenix, the showman reverted to his greatest hits.

Buoyed by a crowd shouting the signature chant of Trump rallies, "Build the Wall! Build the Wall!" he delivered a strident speech reiterating many of his hard-line stances on immigration, even if he did not explicitly repeat his pledge to deport the estimated 11 million people living in the United States illegally.

If in Mexico City he offered something of an olive branch, in Arizona later on he hurled out lashings of red meat.

Ann Coulter, one of the conservatives who had voiced concerns that Trump would use the Phoenix speech to soften his uncompromising approach, could not have been happier.

"I hear Churchill had a nice turn of phrase," she Tweeted, "but Trump's immigration speech is the most magnificent speech ever given."

The view from other, more moderate sections of the conservative movement was condemning. John Weaver, John McCain's campaign manager in 2000 and 2008 and the strategist who headed up John Kasich's bid for the White House, was excoriating:

"Fittingly, any Trump comeback died today somewhere over the Chihuahan Desert as his speech was finalized. #nojudgment #wrongpath #adios."

The Republican high command, which has been almost begging Trump to re-invent his public persona and retool his campaign, would have been delighted by his performance in Mexico City, but may have ended his shouty Arizona speech watching from behind the sofa.

More from the BBC

The crowd at the Trump rally loved the quick turn back to harsh immigration talk

On this day of two Trumps perhaps they recalled the opening lines of Charles Dickens' overly quoted Tale of Two Cities. "It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness."

If Mexico City demonstrated wisdom. Phoenix was an act of folly.

In some ways this display of "Two Trumps" was reminiscent of the days in the post-war years when Democratic presidential candidates used to deliver different messages north and south of the "border" - the boundary in those days being the Mason-Dixon line, which symbolised the demarcation between the north and the south.

Before northern audiences packed with blacks and white liberals they emphasised civil rights and the need to tackle segregation and racial discrimination, but soft-pedalled or failed to mention the issue when they headed south.

In that bygone era, Democrats needed to maintain support in what was then called the Solid Democratic south, their segregationist stronghold, but also appeal to black voters in key battleground states like Illinois, Michigan and New York (yes, in the 1950s the Empire State was a swing state in presidential elections).

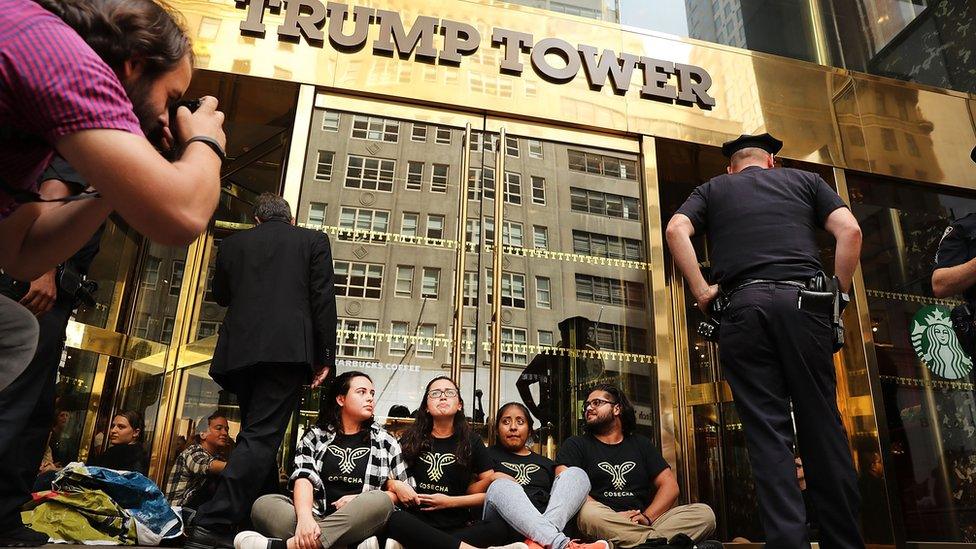

Immigration protesters block the entrance to Trump Tower in Manhattan before being arrested on Wednesday

They needed to keep intact what was called the Roosevelt or New Deal coalition, an unlikely amalgam of ethnic and religious minorities, union members, southern whites and liberal whites, which made them so strong in presidential elections.

Back then, before campaign speeches were broadcast live on cable news channels and covered in real-time on Twitter, this Janus-faced approach often worked.

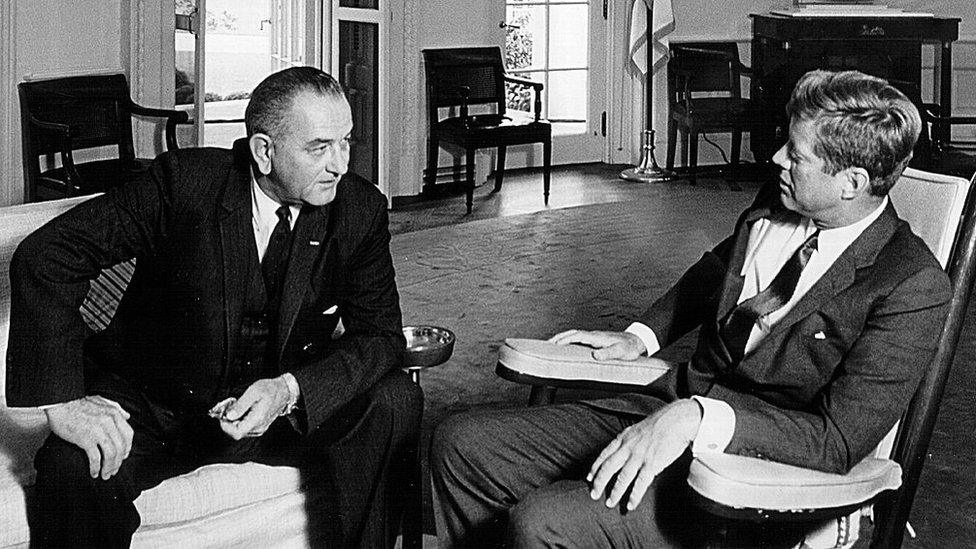

As John F Kennedy proved in 1960, with the help of Lyndon Johnson as his running mate, it was possible to appeal to northern blacks while at the same time keeping much of the segregationist south in the Democratic column.

Yet as Donald Trump reminded us yesterday, different approaches before difference audiences, whether north or south of the border, becomes quickly apparent and obviously jarring in this age of instant and nationalised news.

Indeed, the Jekyll and Hyde character of the two appearances immediately became a major part of the story.

Modern-days Republicans, in some ways, have the same dilemma on immigration as the Democrats had on civil rights: of how to manage and finesse one of the most polarising issues before the country.

Democrats held together a broad and ultimately unsustainable coalition in the early 1960s by changing their message for different audiences

That's why many senior Republicans hoped that a candidate like Marco Rubio might emerge as the party's standard-bearer: a born-again Christian with appeal to social conservatives who could simultaneously appeal to fellow Latinos.

Instead, they ended up with Donald Trump, who has fired up large parts of the conservative base with his anti-immigration rhetoric but alienated moderates and minorities.

In Mexico City, his more respectful and diplomatic remarks offered a blueprint for something nearing the approach that "outreach Republicans" would have wanted to hear much earlier in the year.

But in Arizona, it was the firebrand who stepped up on stage. As a result, some of the billionaire's Latino surrogates are said to be reconsidering their support for him.

In this tale of two Trumps, perhaps they have decided that the Mexican episode was illusory and Arizona presented the authentic Donald. South of the border he cast himself as a president.

On home soil, he returned to being a populist.