US election 2016: America's Great Game as energy superpower

- Published

Presidential candidates pitch US energy policy as a way to improve job prospects for Americans, but the US also has potential to exercise real power farther afield.

What's lost in the coverage of the overnight internet sensation Ken Bone is the question he asked.

He surged to social media stardom as the unassuming guy with a bright red sweater during a corrosive second presidential debate

But the topic he raised - energy policy - will have lasting significance for the next president and the country. That's partly because of American jobs lost and won in the energy industry, which is often the focus during election season.

How the US is using energy in foreign policy

It's also because the US is increasingly using oil and gas as a tool of foreign policy, deepening its involvement in a high-stakes game of pipelines ranging from Russia to Israel to Turkey and even Syria.

An Energy Superpower

The view of energy as a matter of security, not just economic competition, is not new in Washington. But it was Hillary Clinton who gave a significant boost to energy diplomacy.

When she took office as Secretary of State in 2009, her European counterparts were reeling from a bruising battle in an energy war with Russia.

Moscow had cut gas to Ukraine over a payment dispute, closing off its main supply route to Europe in the middle of winter.

Mrs Clinton created a bureau within the State Department to deal with international energy issues in 2011. Since then a domestic boom has transformed the US into the world's largest producer of natural gas, and the US has switched from being a major importer of petrol products to a new exporter.

"Today we have a seat at the table on energy issues around the world in a way that we didn't seven years ago," says Amos Hochstein, the State Department's special envoy for international energy affairs.

"Because of the oil and gas revolution in the United States, and to some degree because of our renewable energy revolution... We're not an energy superpower, we are the world's energy superpower."

A new Cold War

The main power struggles in energy are still with Russia, at a time when relations have reached their lowest point since the Cold War.

Here's what Europe's 'pipeline politics' look like

Energy experts have been talking about a new chill since Moscow annexed Crimea in 2014 and shut down gas supplies to Ukraine for a second time.

This is a war fought not by military means, says Mr Hochstein, but "with economic conflict".

Washington is focused on helping its European allies diversify their energy supplies away from Russia, a daunting task since Moscow provides a third of Europe's gas, with seven states almost entirely dependent on it.

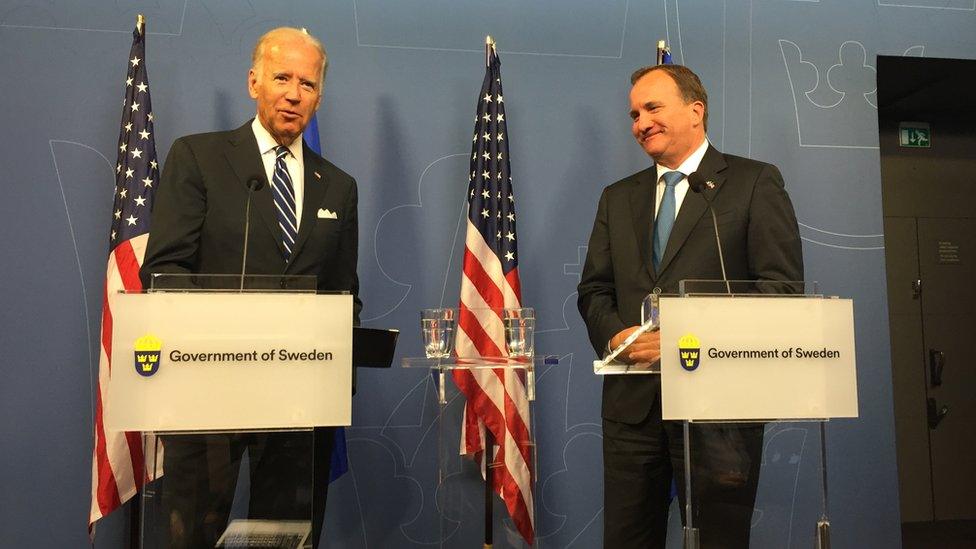

The Obama administration's strategy involves peddling US gas, as the Vice-President Joe Biden did with enthusiasm on a recent trip to Latvia and Sweden in August, calling North America the "energy epicentre for the 21st Century".

It also involves aggressive lobbying against Russia's proposed Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which would reroute gas around Ukraine by expanding the existing Nord Stream 1, which runs under the Baltic Sea to Germany.

In Stockholm, Mr Biden called Nord Stream 2 "a fundamentally bad deal for Europe" that would "lock in greater reliance on Russia and… destabilise Ukraine" by depriving Kiev of lucrative transit fees.

The Nord Stream project has foundered on the shoals of similar resistance from Eastern and Central European states.

But the Russians have specifically accused the US of meddling for entirely political reasons, external, calling it a commercial enterprise necessary to ensure reliable gas transit through Ukraine.

Pipeline 'peace' in the Middle East

Meanwhile, in the eastern Mediterranean, the Americans are on the offence, not defence.

Powered by recent gas field discoveries in the region, the US wants energy co-operation involving Egypt, Turkey, Cyprus, Jordan and Israel. The latter two have just finalised a pipeline deal.

The idea is to create a "physical interdependency" that could set a framework for political co-operations, Mr Hochstein says. Energy creates "an enormous incentive to change mindsets".

That was the case with Israel and Turkey, where the US envoy played a role in brokering the recent rapprochement, including an agreement to pursue a pipeline from Israel's offshore gas field to Turkey.

Indeed, American lawmakers have stressed that natural gas co-operation could "dramatically change Israel's regional position". A recent congressional hearing summary hailed energy's potential to advance peace in the Middle East, external and an energy advisor linked to the Middle East Quartet has advised Israelis to throw Palestinian gas into the mix, external.

The US is hoping that energy will also be a catalyst for Cyprus. The leaders of the Greek and Turkish communities on the divided island are aggressively pushing for a settlement of their decades-old conflict by the end of the year. Without it they will not be able to fully exploit newfound gas resources.

UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon with Cypriot leaders last month

But there's more at stake than Middle East stability. Building a regional export architecture could potentially supply eastern Mediterranean gas to Europe, undermining Russia's dominant position.

How it all comes back to Turkey

All these different strands come together in Turkey.

The position of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has always been crucial to resolving the Cyprus dispute.

And now he needs a settlement in order to get the pipeline Israel agreed to, which would connect through Cypriot waters.

Mr Biden worked that angle during a recent trip to Ankara, noting that Turkey wasn't the only option for Cypriot and Israeli gas exports.

Vice-President Joe Biden made a trip to Turkey to talk energy earlier this year

Egypt was also in the picture, an official familiar with the meeting told the BBC, and the Americans stressed "the urgency of the window closing on Cyprus".

Despite international concern about the fallout of the recent coup attempt, Turkey remains an important energy link between Asia and Europe.

It's a potential conduit for gas from the eastern Mediterranean, and it's the key transit country for a chain of pipelines called the Southern Gas Corridor from the Caspian Sea to Italy, promoted by Europe and the US as a non-Russian option.

Ankara is eager to exploit these opportunities, not least because it wants to reduce its energy dependency on Russia, from which it gets more than 50% of its gas supply.

But President Erdogan is keeping his options open, especially in the wake of anger at perceived Western ambivalence over the failed coup.

He recently patched up relations with Moscow that soured last year over Turkey's downing of a Russian warplane near the Syrian border.

And less than two months after Joe Biden's visit, Mr Erdogan signed a deal for a new Russian pipeline called the Turkish Stream, which would also help Moscow access the European market through Turkey, external.

Russian and Turkish leaders sign a pipeline agreement on 10 October

Russia's pipeline deals can be as much about political messaging and bargaining chips as actual construction, according to Edward C Chow, an energy analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

The Russians "have played chess for a long time and like to scramble the board as conditions warrant," Chow said in a recent report, external.

Either way, Russia has reinforced its energy access to Turkey at a time when Moscow has doubled down its commitment to supporting the neighbouring Syrian regime, an intervention that some analysts argue is motivated by a determination to gain leverage over competing gas interests there, external.

Energy at the ballot box

So the new US president will have a complex chessboard to navigate.

Either candidate seems likely to pursue an aggressive international energy policy.

Their differences focus on jobs and environmental regulations rather than diplomacy.

Donald Trump emphasises lifting restrictions and bringing coal miners back to work, while Mrs Clinton focuses on renewables.

But whoever wins will need to play a long-term, strategic game to shape the future of the global energy map.